.

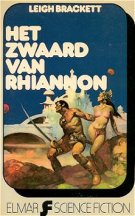

Gulliver Jones on Barsoom? . . . Sure, why not?

After all, Arnoldís

Gulliver Jones and his trip to Mars is often touted as being the source

of John Carterís Barsoom.

The theory was propounded originally, I believe, by Richard

Lupoff, who turned in a fairly polished essay on the subject.

Iím sure you can find it somewhere, and I certainly recommend its reading.

For those purists, I also recommend Edwin Arnoldís novel, which can also

be found on the net.

For my own part, I remain unconvinced.

Burroughs' sourcing and inspirations are far too transparently the works

of Percival Lowell

and other scientists of the age. It was the astronomers who

built up the vision of Mars as a formerly green and lush world now deep

in decay, its continents weathered flat, its seabeds drying, its life ancient

and clinging precariously to oasis, canals and ocean bottoms.

It was Percival Lowell who gave John Carter his amazing jumping ability,

and who gave Burroughs his fifteen foot giants, intelligent but inhuman,

and a decaying society fighting for its survival.

Itís

true enough that Arnoldís romance featured a dying decadent society, an

alien princess, a river of death, and barbarian invaders. But then

again, rivers which are receptacles for the spirits dead appear on Earth

in the Nile and the Ganges. Every adventurer seeks a princess

and contends with Barbarians. So, the case for Arnold, I find

doubtful.

Itís

true enough that Arnoldís romance featured a dying decadent society, an

alien princess, a river of death, and barbarian invaders. But then

again, rivers which are receptacles for the spirits dead appear on Earth

in the Nile and the Ganges. Every adventurer seeks a princess

and contends with Barbarians. So, the case for Arnold, I find

doubtful.

But what the hell. Even the allegation, whatever

its merits, has given Gulliver Jones a lease on life he would never have

had, except as a quasi-part of Burroughs Martian canon. Itís

lead to fan debates, new publications of his novel, and even a distinctly

Burroughsian Marvel comic series.

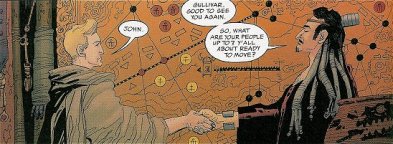

Most tellingly, in ĎThe League of Extraordinary Gentlemení,

no less than the great Alan Moore, sees fit to join these remarkable visitors

to Mars, having them link their forces in an assault against alien invaders.

Well, if Alan Moore says Gulliver Jones is on Barsoom with John Carter,

then its good enough for me. Thatís all but next to Edgar himself

rising from his sleep to wink at us.

Well, if Alan Moore says Gulliver Jones is on Barsoom with John Carter,

then its good enough for me. Thatís all but next to Edgar himself

rising from his sleep to wink at us.

But if we play this game, if we, as an intellectual conceit,

accept Gulliver Jones as a quasi-member of Burroughs Martian canon, then

shouldnít he be on Barsoom proper with John Carter, Ulysses Paxton, Tan

Hadron, Ras Thavas and the rest?

(I note that there is a ĎWold

Newtoní essay out there arguing that Ulysses Paxton is actually Gulliver

Jones, or something, but frankly, thatís a bit too far fetched for me).

But if Jones is on Barsoom, then the question arises,

where the hell is he?

At first, it seems that there is very little resemblance

between Gullyís Mars and Carterís Mars. Carterís Mars is a

dry and forlorn desert world. Gully, on the other hand, enters

a world with a sea, and with rivers and forests. Gullyís

river of death leads north, Carterís leads south. Carterís world

has all sorts of fierce many legged critters, Gullyís creatures seem less

extraordinary.

On the surface, it seems that Arnold hasnít read his Lowell,

and Burroughs harsh desert Barsoom is a very different place than the gentler

more idyllic land Gully is familar with.

But that just means we have to be creative.

And attentive. All too often, creativity is a tender young

thing of flexible morals, and detail is the man with the cash.

One gets the best out of the other. So letís take a close look

at Gullyís world....

Gulliver Jones comes to the northern hemisphere of Mars.

All right, thatís hardly controversial. But on the other hand, we

donít appreciate just how far into the northern hemisphere it actually

is. The glaciers of the north pole are only a few lacksadaiscal

days journey away from Seth, the last city of the Hither people.

Gulliver Jones comes to the northern hemisphere of Mars.

All right, thatís hardly controversial. But on the other hand, we

donít appreciate just how far into the northern hemisphere it actually

is. The glaciers of the north pole are only a few lacksadaiscal

days journey away from Seth, the last city of the Hither people.

Consider: Gulliver winds up on Mars, near

the city of Seth, where he meets and falls in love with the Princess Heru.

Seth appears to be on the shore of an opal sea, but it also borders a river

or two. The river is obviously draining into the sea.

The area is described as rich temperate forest land.

Once Heru is kidnapped by the Thither people who have

sailed across the sea. Gulliver sets out to rescue her.

He gets knocked out and knocked into the water for his troubles, landing

on some floating booty and drifting on the current, which appears to take

him northwards. Eventually, he makes his way to shore, finds

a friendly village and procures a boat. His attempts at sailing,

however, lands him in the river of death, which leads him to the glaciers.

As nearly as I can tell, this takes all of three days at most.

Now, it seems obvious that from the direction of the sea

current, that the sea is flowing north, and that the river of death flowing

northward, is actually draining from the sea itself.

Saltwater tends to be less prone to freezing than fresh water.

So its likely that the Ďriverí that abuts the glaciers is heavily salted,

literally, it comes with freeze protection. And in fact, its

likely that the salt water river may be the source of the erosion of the

glacier that Gully finds.

However, by odd circumstance, it appears that the glacier

has melted a bit, or gone through periods of melting and freezing, which

occasionally leaves the frozen dead exposed. Thereís a very odd climate

phenomena here that will demand attention.

Gully spends a night among the dead, finds a friendly

scavenger, and gets the hell out of there. He wanders along

until he encounters a friendly woodsman and spends the night with him.

Thereafter, he walks for, at most, a few more days until he comes to the

land of the Thither people. On land, he goes on foot, which means

he can hardly be traveling too fast. He is not mounted.

In other words, in something less than a week, perhaps

as little as four or five days, Gully has traveled all the way up from

Seth, the Hither city, to the Polar Glacier, and then back down south to

the Thither lands, where he learns that Heru is only two days ahead of

him.

Now letís think about this. Gully is not traveling

fast. For several of his days, he is on foot, even when traveling

by boat, he isnít under sale, but simply paddling occasionally with the

current.. He dawdles in the company of various people, he gets lost

a couple of times, taking the wrong path more than once. He

takes the long way round.

In short, he canít possibly have traveled any great distance.

Nor, for that matter, can Heru have traveled all that far, although the

matter is more complex. While we might think that a relatively

straight line by boat should be much faster, sheís only two days ahead

of Gulliver. This suggests that her travel time by boat might

be as little as two or three days.

Well, letís speculate that its not a terribly big sea

if it can be crossed in two or three days. An ocean is right

out of the question. The likelihood is that it is likely a

relatively small body of water.

And in fact, it might be even smaller than Heruís two

or three day crossing suggests. Thereís nothing to indicate

that the Thither people are particularly good sailors, or that the winds

and currents favour them. Thereís nothing to indicate that they pursued

a direct route home, without stops. Indeed, the situation seems

quite the opposite. A woman that Gulliver meets on an island has

news of the Thither fleet and its northern progress. So clearly,

its not taking the direct route, and its making a few stops along the way

if its progress has become common gossip. Itís quite possible

that their route was only marginally less circuitous and slow than Gulliverís

own. Which suggests a quite small sea after all.

There are a few other clues. Gulliver

at one point makes reference to the short Martian night. Well, we

know that Martian days are as long as Earth days, a half hour longer, even.

So to call the Martian night short is suggestive. Living

up in the northern latitudes, I can testify that in the summer, due to

the angle of the Earthís axis, days get very long and nights become very

short, only a few hours. Again, another suggestion that Gulliver

is located at extremely northern latitudes.

Gulliver observes fur bearing creatures, including an

elklike animal, and two ratlike monstrosities the size of elephants.

Now, thereís little enough to make of this under normal circumstances.

But on Barsoom, the only fur bearers inhabit the region of the poles.

And of course, the Ďopalí or whitish sea, suggests ice

and frost, again, implying that this area is near the poles.

All of this goes towards putting Gulliver in extreme northern

reaches of the planet, whatever planet he is on. All

of this seems to add up to a case of the Ďseaí and the Hither and Thither

people both being far in the northern hemisphere, just a short distance

from the glaciers of the north pole.

Assuming that Gully is travelling sixty miles a day (given

that heís mostly drifting with the current, or slogging along on foot thatís

an incredible rate of speed) he seems to make the edges of the polar cap

in about four days. Which puts it at roughly 240 miles away, call

it 300 at most. This is hardly a fast distance.

Now, letís stop for a moment, having exhausted this line

of inquiry, and turn to the people Gully encounters.

They are not Burroughs Red Martians, thatís for sure.

For one thing, these people are white, this is referred to a number of

times. They have startling purple eyes, some of them.

Their hair is of varying colours, brown is mentioned twice, and I think

that there are blonds in there as well. And, they have unusual

mental powers, one person teaches Gulliver the language through telepathy,

another is able to use his mental abilities to shield himself from lances.

They are an indolent and dying race, given to apathy, lazy and nonviolent,

driven to their last refuges by barbarians. Seth is the

last, or one of the last Hither cities. Across the sea, we

see a vanished Hither city, and learn that the Hither folk once ruled far

and wide.

Well, thatís pretty simple then... Theyíre

Orovars. Burroughs Orovars are a white race, with fair hair

and features, now extinct on much of Barsoom, but still remaining in a

few decadent enclaves. Most strikingly, the mental powers of

some the Orovars that we see in Burroughs are the most developed on all

of Barsoom.

And the Thither people? Theyíre quite interesting.

The Thithers are red men, like Burroughs own red men. Both

John Carter and Gulliver Jones live in a Mars where the red race has supplanted

the white.

But these are not typical red men, not John Carterís red

men. Rather, Gulliver Jones makes constant reference to them

being hairy shaggy brutes. On Barsoom, only one race was known

for its body and facial hair, and that was the yellow Okar people.

This red race seems like a mixture of the red martians

of John Carter, and the hairy okar types. Interestingly, the

Okarís survived inside the north pole on Barsoom, so we might expect that

possibly red men of the northern latitudes in certain areas might share

a disproportionate mix of Okarian blood.

Interestingly, there is one passage where Gulliver Jones

describes one of his red men as yellow or yellowish. This is

normally read as perhaps a showing of superstitious fear, but it may also

be a reference to actual skin tones, in which case, we have another hint

as to a mixture of Red and Yellow men.

Once again, of course, the Thitherís ethnic make up suggests

that we are in the extreme north of Barsoom.

The species that Gulliver notes, on the surface, seem

to have no resemblance to plants or animals that John Carter encounters.

On the other hand, Gulliver seems more of a botanist than a naturalist.

Several times he gives detailed descriptions of alien plants of various

types but his descriptions of animals tend to be cursory at best, he never

goes into detail, merely preferring to call this an elk, that a deer, this

an ape and so forth. In only one case, describing a battle

between two elephant sized ratlike creatures, does he give us any description.

And its not much more than what Iíve just said.

So what is going on with Gulliver. Is he actually

finding mundane animals among these plants? Or is he actually shortchanging

his descriptions, describing the local animals in terms of creatures they

most resemble on Earth, and only with the elephant/rats being put to trouble?

Perhaps the Elk that tows him to shore actually has eight

legs. Gulliver doesnít say it does, but then, he doesnít say

it doesnít. So perhaps this ĎElkí is actually a semi-aquatic

variety of Thoat. And perhaps the black apes that he mentions are

six limbed and not four, and actually dwarf relatives of the great white

apes. The rat-elephants may be furred cousins to the Zitidars.

Gulliver frequently mentions the forests, but we should

note that forested areas are not unknown on Barsoom. There

are still at least two substantial forests left: Kaol and Invak.

But from this, we have two problems: If indeed

Gulliver is on Barsoom, why is his environment so clearly subtropical or

temperate? Heís three hundred miles from the polar glacier,

why arenít the Thither and Hither all freezing to death?

And of course, the second question is where precisely

is he? On a Barsoom where nations fly, where ravenous hordes

plundered the very limits of the world, how is it that even a small sea

could have gone unnoticed? Why are both the Hither and Thither

so backwards, where are their flyers and radium rifles?

The answers to these questions spring from the same sources:

Tharsis.

Consider, both the Hither and Thither regions drain into

a small sea, which itself drains into rivers or canals which drain towards

the polar glaciers. However, a look at the topographic map

tells us that the polar zone is surrounded by seas. Normally, it

should drain out, not in.

For Gulliverís geography to work, it has to drain out

from a relatively higher elevation, to lower ancient seabed elevations

that are still close to the polar levels.

The Tharsis volcanic regions are the highest areas on

Barsoom, and extend far into the north, up to the sixtieth parallel.

The two highest Tharsis regions in that area, including the volcano, Alba

Patera and Tempe Terra, form a sort shallow midland or lowland cup between

them. Thus, we would have here a relatively sheltered area,

constantly draining the run off moisture from the sheer cliffs in the distance.

Moisture from the cliffs would collect into rivers, it would support forests

and plant life, and eventually collect into a small sea or large lake.

Eventually, of course, the lake would drain down into

the ancient sea beds, but up around the area between Tharsis and the poles,

the sea beds are at their shallowest. So you might well get

a river that reached the outer limits of the glaciers.

Such an area would be almost invisible to explorers, unless

you knew where to look. The Tharsis region would be impassible

and fierce for flyers and likely well avoided. It would be

too far north for the Green Men to visit habitually. And if

the sea was salt, then the river would be considered unuseable, being a

salt river. Worse than useless for Barsoomians seeking fresh

water. There would be little incentive for Barsoomians to seek

the source of a useless saltwater river, no matter how many frozen corpses

floated down it.

And, we should note, that before John Carter, Barsoomians

seemed to show little inclination to explore. They might wander

about freely, but many Barsoomians showed a profound obliviousness to,

and indifference to, foreign lands. Even lands not too far removed

from their own. So its entirely likely that Barsoomians did

not go out of their way to wander into a region that had been previously

judged poisonous, inhospitable, dangerous and barren in order to see if,

by some off chance, there was still a garden of eden there.

And of course, there may be another reason.

The Thern cult of Iss may well have been active here. In fact, their

presence of a sacred river to the afterlife all but guarantees the presence

of the Therns. The Thern society may well have kept this last

dwindling refuge of Orovars a secret, seeing it as a northern reflection,

perhaps, of their own blessed valley and river. Certainly the

Therns are the one people who could have gone among the Hither and escaped

notice.

The lack of technology and technical sophistication is

unusual for Barsoom, but not unheard of. The Manator kingdom,

very nearly as remote, also lacks flyers and radium rifles.

But there are other oddly archaic features of the Hither. They

appear to be polytheists, although we donít receive much detail.

In addition to the ĎIss Cultí faith of the river of death, there is also

evidence of Sun (Tur?) worship and allusion to multiple Gods.

The Hither people are undoubtedly an isolated leftover remnant living off

of past glory and cut off from the outside world by geography and by the

Thither people, so its not surprising that they are not up on modern Barsoomian

technology.

And indeed, it seems likely that the hairy hybrid race

of red men and okars is itself, almost as isolated as the Hither, with

similar religious traditions and a similar lack of technology.

The hybrids society, like the Hithers, seem focused on the sea and its

tributary rivers and forests, with little interest in the inhospitable

deserts beyond.

Now, on to the final and most important question:

Why is it so warm, so far north? The simplest reason

of all. Volcanism. Mars has cooled down substantially,

and the volcanoes are no longer highly active. But Tharsis was the

most active volcanic region on Earth, and the residual heat warms the bowel

shaped midland between its peaks, creating a warm temperate microclimate

in this isolated region.

It is remarkable, of course, but remember, Barsoom has

other such hidden micro-environments, from the Lost Seaís of Korus and

Omean, to hidden valleys and forests like Invak, Ghasta and Kamtol, to

far more bizarre regions, such as the Kaldaneís land, Bantoom.

Thus, the hidden lands of the Hither and Thither, with

their forests, rivers and small sea, and their relic white race, and their

hybrid red race, are not so unusual or abnormal as to be beyond the ranges

of what we have already seen on Barsoom. Rather, it is just

one more forgotten corner of the dying world.

And there you have it, weíve found Gulliver Jones upon

Barsoom, sketched out his home, and defined his stomping grounds.

We hope youíve enjoyed....

Postscript

There is another, slightly less satisfactory, but perhaps

equally valid explanation. Gulliver Jones may simply be further

into the past than John Carter. Itís been suggested by

some that John Carter did not only travel through space, but through time

as well, in reaching Barsoom. If this is correct, then the fate of

Barsoom is written, it will sometime after the Warlord, become our Mars.

...

...

Moorcockís Michael Kane ~ Bracketís Matt Carse

If our heroes travel through time as well as space, then

it is quite possible that they have different stops.

Thus, Carter travels back to the dying world. Gulliver travels

back even further to the twilight of the Orovars. In

support of this, we might consider Moorcockís Michael Kane, who definitely

travels into Mars past, as well as Bracketís Matt Carse, who also ventures

into the Martian past (though he gets to the planet itself by normal enough

means).

Of course, the trouble with that theory is that John Carter

does not actually seem to travel into the past, his adventures on Barsoom

appear to be contemporary, and in fact, there is occasional real time communication

between Barsoom and Earth, as noted in the use of the Gridley Wave to chronicle

certain Barsoom adventures, and later in the Moon Maid. Barsoomians

even build a spaceship to reach Earth in the 21st century.

In short, in the Burroughs universe, Barsoom is contemporary with Earth.

And further, there seems little evidence for actual time

travel in the Burroughs universe, at best, there is a facility to access

the memories of ancestors or descendants through some line of reincarnation,

but that falls far short.

Nor is there any indication of time travel in Gulliver

Jones. When he commands the carpet, there are explicit orders as

to locations, but he makes no suggestion or hint relating to time, nor

says anything which can be construed as referring to time.

There is no evidence that the carpet has moved through time.

Indeed, quite the opposite, it appears that when the carpet returns him

to Earth, an equivalent period of time has passed since his departure.

This suggests that the Carpet remained in normal time throughout.

So, despite the examples of Matt

Carse and Michael Kane, and the speculations of fans, I would be inclined

to reject the Ďtime travelí theory.

And, as noted, if such a person as Allan

Moore chooses to unite the two.... Well, that settles it for

all other intents and purposes.

Post

Postscript

Refining

the Opal Sea

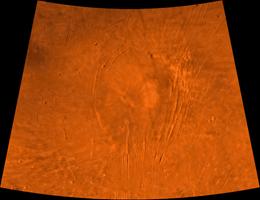

For the record, the most likely single spot for Gulliver's

Opal Sea is probably at Tempe Terra.

If you look on the maps, you'll see that the Tharsis uplift

region in the north has two distinct horns. One is Alba Patera, an

immense shield volcano.

The other is Tempe Terra, which seems to be a rugged hill/highland

area marked by straight grooves (canals?) and apparent river structures.

The territory seems close to what Arnold describes for Gulliver.

Tempe Terra also forms a sort of bowl or crescent at its

top, which would form the shore of the opal sea. The downside is that it

seems to slope steadily. But even a shallow rise on the northern

rim would trap waters in a shallow sea or lake.

I suspect that the Opal Sea is a relatively shallow body

of water less than 100 feet deep, and quite likely, only dozens, or even

a dozen feet deep. It's probably more like Lake Chad, Lake Winnipeg

or the Aral Sea than it is like Lake Victoria, the Caspian or Black Sea,

or the Great Lakes.

The Opal Sea is almost certainly not a stable body of

water. Left to its own devices, it would have evaporated long ago.

And in fact, its likely simply a geological anomaly, a fragment of the

polar ocean stranded by a trick of topography when the rest of the ocean

receded.

The Lost Sea of Korus is, in comparison, a stable body

of water. Its moisure is trapped by the Otz Mountain ranges which

surround it, and its waters are continually replenished by the Iss River.

In contrast, the Opal Sea has no ringing mountains to

secure it, particularly on its northern lee. So it should be in a

constant state of drainage and evaporation.

Its existence comes from being constantly replenished

by waters running or drifting down from the edges of the Tharsis uplift.

Essentially, Tharsis, like a mountain range, is above

the levels of the moisure bearing clouds. So, when air is moving

clouds along, wind currents eventually bring them up against Tharsis, and

they pile up like rush hour traffic. The density of the clouds and

the density of the moisture in them increases, and eventually this precipitates

as rain or run off down the side of Tharsis in the form of mountain streams.

This is why, likely, some of the most fertile remaining

regions of Barsoom, like Bantoom or the Kaolian forest, are clustered around

Tharsis.

Of course, as the water vapour in the atmosphere, or the

water bearing clouds slide up against Tharsis, they'll tend to move along

its length, sliding north or south. That's as long as there's a relatively

straight surface. If on the other hand, Tharsis geography cups or

forms a crescent or wedge, then you'll get a collection point for moisture

far more effective than we see. These geographical areas literally

form a kind of pocket or trap for moisture. Tempe Terra is one such

area where you would expect to see a lot of moisture getting trapped.

In addition to normal planetary moisure, Tempe Terra is

also probably collecting any moisture coming off the North Pole, one of

the major repositories of water left in the northern hemisphere.

So, as you can see, there'd be plenty of water continually

flowing in to sustain the Opal Sea, even though it must be losing its water

at an astounding rate.

The

Ice Valley of the Dead

As a further thought, I'm not sure that the glacier full

of corpses that Gulliver encounters is actually at the north pole.

There are two problems. If we locate the Hither and Thither at the

opposite arms of Tempe Terra's shoreline crescent, then the North Pole

ice cap still seems too far away by some hundreds of miles, to match up

with Gulliver's journey. Secondly, the north polar cap is a

glacial highland surrounded by lowlands, so in order for it to work, the

river of death would have to flow upwards.

On reflection, I'm inclined instead to think that the

Valley of Death that Gulliver finds is actually a glacial outlier to the

north pole, but not actually part of the north pole ice. It's located

on the sea bed, so it may have actually begun as an ancient iceberg calving

off the pole, trapped in a lowland as the seas dried up. It's likely

sustained by cold polar area temperatures, remnant ice/sea water, by moisture

leaching off the north pole, and by waters from the river of death.

The sub-polar regions of Barsoom are probably spackled

with these little remnant outlier glaciers, much as some parts of the subpolar

regions of North America are.

The

Cult of Iss and the Therns

Oddly, in one of those 'stepping on your grave' moments,

Gulliver actually does contain a direct reference to Isis.

The moment comes when Gulliver and Heru are in a library,

and she comes across what she says is a book chronicling Earth's legendry,

Isis is mentioned, as is Phra (the Phoenician, immortal hero of an earlier

Arnold book and according to some, the inspiration for John Carter).

The Phra bit is obvious self referencing, and the Isis referred to is clearly

an Earth goddess. Nevertheless, if Earthly Gods and Heroes are known

of on Gulliver's Mars, then we might infer a borrowing or inspiration of

names. It's an odd little coincidence.

It's almost certain by the way, that the region has some

sort of cosmological significance to the Therns. For one thing, it

is on almost exactly the opposite side of the planet from Korus.

For another, while the Iss River drains into Korus, the River of

Death drains out of the Opal Sea. In short, in geographical

terms, the Opal Sea would appear to the Therns as a sort of exact reverse

mirror image of their sacred land. They would probably have

some metaphysics on the subject.

And its likely that the Therns are aware of the Opal Sea.

If they're aware of Okar which is even more remote and inaccessible, it

seems almost certain that they'd be familiar with the region.

The

Burning Star Reconsidered

In Gulliver Jones, the climax of the novel seems

based around a close encounter with a meteor or asteroid, which blazes

through the atmosphere, causing a ferocious heat wave and drought through

the region, before withdrawing.

In astronomical terms, of course, that's pure rubbish.

Asteroids and even comets are relatively inert bodies. They don't

heat things up from a long way off. Indeed, while an asteroid or

meteor's approach might well heat things up, this would be for, at best,

only minutes before it hits. Gulliver's heat wave lasts for several

days, even weeks, drying out the region almost completely, and in fact,

drying out underground wells.

So, if we accept that physics in Gulliver's world has

even the most half-assed resemblance to our world, then clearly, Gulliver

has completely misinterpreted events.

What's really going on? Two things. First,

there is likely a close approach of a comet. On Earth, Comets were

considered evil signs, harbingers of doom, and carried with it a lot of

bad karma. Gulliver's carrying on that baggage. And Mars, being

closer to the asteroid belt and more likely the victim of more frequent

rockfalls from the sky, probably has its own 'anti-comet' baggage.

So, its likely that the appearance of a comet in the sky is taken as a

bad omen, and everything bad that happens gets attributed to the comet.

The second thing is equally straightforward. Remember

that the Opal Sea and its peoples are in the extreme north, in a sub-arctic

region. They should be frozen solid. The reason that they are

not is volcanic warming, like Iceland in our own north, geological or volcanic

heat is making the area far warmer and more liveable than it should be.

Well, the thing with geological or volcanic heating is

that occasionally it gets a little unstable. Volcanoes occasionally

heat up, sputter, cough, or ratchet up the temperatures. So the heat

wave that Gulliver experiences, and the drought, are all attributable to

a mild uptick in volcanic activity, one which dries up the streams running

down Tharsis, and dries out the underground water.

The comet which happens to be appearing at the time is

considered the ill omen, and is blamed for the heat wave. But in

reality, the heat is rising up, not coming down.

A

Final Odd Coincidence

This one does not involve Burroughs at all, but rather,

myself. Referring back to the Library scene, Gulliver persuades Princess

Heru to read him a bit of some treatise on philosophy, which she herself

finds stuffy and boring:

"....And from the midst

of that natal splendour, behind which was the Unknowable, the life came

hitherward; from the midst of that nucleus undescribed, undescribable,

there issued presently the primeval sigh that breathed the breath

of life into all things. And that sigh thrilled through the empty

spaces of the illimitable: it breathed the breath of promise over the frozen

hills of the outside planets where the night-frost had lasted without beginning:

and the waters of ten thousand nameless oceans, girding nameless planets,

were stirred, trembling into their depth. It crossed the illimitable

spaces where the herding aerolites swirl forever through space in the wake

of careering world, and all their whistling wings answered to it. It reverberated

through the grey wastes of vacuity, and crossed the dark oceans of the

Outside, even to the black shores of the eternal night beyond."

This seems a version of the 'let there be light' shtick of

genesis. But reading it, I found strange echoes of my own theories

of Earth's life force or biomagnetic field, sweeping outwards, transforming

worlds in our solar system and beyond, as expressed in essays ranging from

the "Are Barsoomians Human"

to the "Secrets of Va-Nah" and "Eurobus

Revisioned."

Of course, its all fluff and coincidence, sound and fury,

signifying nothing more than to imprint our own designs upon the void.

But interesting nevertheless, n'est ce pa?

![]()

![]()