.

H.G. WELLS' BARSOOM!

CONTENTS

Introduction

H.G. Wells' Mars

H.G. Wells' Martians

on Mars

Barsoomian

Creatures on Wells Mars? Apes and Men, oh My!

Wellsian

Creatures on Barsoom: Kaldanes and Rykors, Oh My!

Locating Wells'

Martians on Barsoom

Evolution

of Wells' Martians on Barsoom

A Little Problem

John Carter's

War of the Worlds

Edgar Rice Burroughs

~ War of the Worlds Frontispiece and Title Page 1913

~ H. G. Wells

Introduction

It is now an established literary conceit to

merge Edgar Rice Burroughs' Barsoom with the malignant Martians of H.G.

Wells. It’s been done by George

Alec Effinger, in “Mars: The Home Front,” in the Kevin J. Anderson

anthology War of the Worlds: Global Dispatches as well as by Alan

Moore at the opening of his second volume of The League of Extraordinary

Gentlemen.

Further, fans and theorists, including the Wold

Newton people, have written extensively of the mixing and matching

of the worlds. Personally, I tend to take the Wold Newton stuff

with a grain of salt, those people have too strong a tendency to discard

inconvenient facts and invent imaginary facts to make their theories fit.

But nevertheless, H.G. Wells’ Mars and Burroughs' Mars

have been mixing reputably and disreputably for quite some time now.

Well, what of it? After all,

both A Princess of

Mars and War of

the Worlds are in public domain, and any author is free to mix

and match them in any old way. They are both Mars stories,

written originally in or around the same era, and arguably the most famous

such stories of the age. Joining them up is as natural as Frankenstein

vs. Dracula. After all this time, the urge to merge them as

some sort of pastiche is as natural and relentless as gravity.

But is this simply a Frankenstein creation, a lumbering crudely

sewn monster, bolts sticking out of its neck, swinging about wildly as

mismatched parts grind together? Or is there the possibility

of something more elegant?

But is this simply a Frankenstein creation, a lumbering crudely

sewn monster, bolts sticking out of its neck, swinging about wildly as

mismatched parts grind together? Or is there the possibility

of something more elegant?

Can we actually go into H.G. Wells, version of Mars and

Martians and find traces that we could call Barsoom? Is it

possible to look through the Barsoom stories and find things that would

point towards Wells’ invaders? Could we actually locate

the home of Wells’ Martians on Barsoom? Could we find related

species? Can we place Wells invaders in an ecologically and

evolutionarily sensible context on Barsoom?

In short, can Wells Mars and Martians, and Burroughs Barsoom

be fit together?

I think that the answer to all these questions, is yes.

H.G.

Wells' Mars

On the surface, the world of Barsoom has no place for

the implacable Wells' Martians. And on the other side of the

coin, it hardly seems that Wells contemplated humans or white apes or green

men on Mars. And yet, if we study the canon carefully,

there does seem to be a bit of imaginative scope within Wells which might

admit to mixing in Barsoom.

Let us consider the Mars delivered to us by H.G. Wells.

From War of the Worlds, published in 1898, there is this broad description:

“The planet Mars, I scarcely

need remind the reader, revolves about the sun at a mean distance of 140,000,000

miles, and the light and heat it receives from the sun is barely half of

that received by this world. It must be, if the nebular hypothesis has

any truth, older than our world; and long before this earth ceased to be

molten, life upon its surface must have begun its course. The fact that

it is scarcely one seventh of the volume of the earth must have accelerated

its cooling to the temperature at which life could begin. It has air and

water and all that is necessary for the support of animated.

Nor was it generally understood that since Mars is older than our earth,

with scarcely a quarter of the superficial area and remoter from the sun,

it necessarily follows that it is not only more distant from time's beginning

but nearer its end. The secular cooling that must someday overtake

our planet has already gone far indeed with our neighbour. Its physical

condition is still largely a mystery, but we know now that even in its

equatorial region the midday temperature barely approaches that of our

coldest winter. Its air is much more attenuated than ours, its oceans have

shrunk until they cover but a third of its surface, and as its slow seasons

change huge snowcaps gather and melt about either pole and periodically

inundate its temperate zones. That last stage of exhaustion, which to us

is still incredibly remote, has become a present-day problem for the inhabitants

of Mars. Their world is far gone in its cooling and this world

is still crowded with life...”

The remark about oceans still covering a third of the world

suggests that even at this time, there was still some consensus that the

dark spots were oceans or seas. But even by this time, the idea was

being increasingly adopted that Mars oceans were gone, or at best, damp

remnants.

Lowell's

Mars

The picture of Mars here as a dying world, its oceans withering, its air

attenuated, is not significantly different than the one Percival Lowell

would develop, or that Arnold in his Gulliver Jones might embrace.

It’s not too different from Burroughs' Barsoom, and in fact, in loose terms,

it represents the state of science knowledge and thought.

The picture of Mars here as a dying world, its oceans withering, its air

attenuated, is not significantly different than the one Percival Lowell

would develop, or that Arnold in his Gulliver Jones might embrace.

It’s not too different from Burroughs' Barsoom, and in fact, in loose terms,

it represents the state of science knowledge and thought.

But Wells gives us a little bit more of his Mars.

The year before

War of the Worlds, he wrote a story called “The

Crystal Egg,” which stands as a sort of indirect prequel to War

of the Worlds. The story concerns an odd crystal object

in a vendor’s curio shop, and a Mister Cave, the proprietor of the shop

who discovers that he can see into the crystal, into another world, Mars.

Mister Cave’s world is identified as Mars within the story,

and for very good reasons. This world has a regular cycle of day

and night equal to our world, the sun is a little smaller, the midnight

sky a little darker, it has two small swiftly moving moons, and most

damning, the same stars and constellations, Sirius, the Pleiades, Aldebaran,

and the Great Bear, in our sky are recognizable on this world. . .

Which must mean that it is within the same solar system!

And the fact that the stars and constellations are the

same, means that the crystal egg is giving a glimpse into a location on

the northern hemisphere of Mars.

H.G.

Wells' Martians on Mars

It isn’t clear whether Wells had War of the Worlds

in mind when he wrote “The Crystal Egg.” It’s quite possible,

that he’s got two different Mars in mind. In the Egg, Wells

describes three kinds of apparent being on Mars, the predominant one being

a winged flyer. But there is another Martian race, larger and

more dangerous, consider this excerpt from the short story:

“...on the causeways and

terraces, large-headed creatures similar to the greater winged flies, but

wingless, were visible, hopping busily upon their (two) hand-like tangle

of tentacles....Mr. Cave was unable to ascertain if the winged Martians

were the same as the Martians who hopped about the causeways and terraces,

and if the latter could put on wings at will. He several times saw (animals)

feeding among certain of the lichenous trees, and once some of these fled

before one of the hopping, round-headed Martians. The latter caught one

in its tentacles, and then the picture faded suddenly and left Mr. Cave

most tantalisingly in the dark.”

My, my. So here Wells has large-headed or round-headed

Martians, wingless, with two tangles of tentacles, which move around the

ground and preying upon other creatures. Now, compare this

description, from War of the Worlds:

“They were, I now saw,

the most unearthly creatures it is possible to conceive. They were huge

round bodies - or, rather, heads - about four feet in diameter, each body

having in front of it a face. This face had no nostrils- indeed, the Martians

do not seem to have had any sense of smell, but it had a pair of very large

darkcoloured eyes, and just beneath this a kind of fleshy beak. In the

back of this head or body- I scarcely know how to speak of it - was the

single tight tympanic surface, since known to be anatomically an ear, though

it must have been almost useless in our dense air. In a group round the

mouth were sixteen slender, almost whiplike tentacles, arranged in two

bunches of eight each. These bunches have since been named rather aptly,

by that distinguished anatomist, Professor Howes, the hands. Even as I

saw these Martians for the first time they seemed to be endeavouring to

raise themselves on these hands, but of course, with the increased weight

of terrestrial conditions, this was impossible. There is reason to suppose

that on Mars they may have progressed upon them with some facility.”

Note the big heads, the common description of the tentacle

clusters as hands, and the facility with which the Martians on their home

world hop about on their ‘hands’, while the ones on Earth struggle to do

so. The Martians on both worlds are predators, preying on mammals

or mammal-like animals. These particular “Crystal Egg” Martians,

seem very close, perhaps identical to the War of the Worlds Martians.

As for Martian machines, in the “The Crystal Egg” we have

these interesting passages:

“On another occasion a

vast thing, that Mr. Cave thought at first was some gigantic insect, appeared

advancing along the causeway beside the canal with extraordinary rapidity.

As this drew nearer Mr. Cave perceived that it was a mechanism of shining

metals and of extraordinary complexity. And then, when he looked again,

it had passed out of sight.”

Not quite a Martian War Machine from War of the Worlds.

But it does have a loose passing resemblance to Wells description of the

Martians handling machines, which are described as swift, metallic insect-like

machines of extraordinary swiftness and complexity, as we see here:

“In this way the curious

parallelism to animal motions, which was so striking and disturbing to

the human beholder, was attained. Such quasi-muscles abounded in the crablike

handling-machine which, on my first peeping out of the slit, I watched

unpacking the cylinder. It seemed infinitely more alive than the actual

Martians lying beyond it in the sunset light, panting, stirring ineffectual

tentacles, and moving feebly after their vast journey across space.”

In short, “The Crystal Egg” seems an effective prelude to

the War of the Worlds, giving us a glimpse of Wells Martians on

their home world. There is a hidden subtext, one which Wells

never alludes to, but which must certainly have occurred to his readers,

and which may have been in his mind.

The Crystal Egg, it is shown, is but one of many sitting

on elevated spires in the Martian city. Moreover, it is one

that the flying Martians periodically peer through, as they do others.

It seems that these Eggs have been sent out by the Martians to spy or observe

other worlds. Mr. Cave is so consumed by his observations that

he attempts to make contact with the Martians who occasionally observe....

And is later found dead. His death, while observing, is attributed

to natural causes, as he is a lonely man in poor health. A

mysterious stranger is out to buy the egg, which thereafter mysteriously

disappears.

But was it? Certainly, the Martians seemed

to be the source of the Eggs. These Eggs were arranged in an

organized fashion within their city, and they seemed well aware of its

use. But just as clearly, they were employed for covert observation,

one may assume that if they wished to make actual contact with humans,

they could have easily devised some equivalent means. Mr. Cave’s

death, coming after his attempts to make contact with the Martians, and

shadowed by the mysterious purchaser and mysterious disappearance, leave

a slight hint of malicious proceedings....

Almost as if Cave’s Martians were planning something unpleasant

for our little world, perhaps an invasion? A ‘War’ of

the ‘Worlds’?

Now, we’ll be honest here. So far as I know,

Wells never came out and said, ‘The Crystal Egg’ was a warm

up prequel story for ‘War of the Worlds’, I was dropping a few hints to

my fans, Mr. Cave was killed by the invaders, and the Martians of that

story are definitely the ones of my novel.’ He never

said any of that.

So, effectively, we are speculating. On the

other hand, the descriptions of some of the Martians and Machines of ‘The

Crystal Egg’ resemble War of the Worlds Martians to an uncommon

degree, even to the same idiosyncratic terms of identification, such as

‘hands’ for tentacle clusters. Mr. Cave is surrounded by suspicious

events, and the two stories are written only a year apart.

So it’s almost certain that ‘The Crystal Egg’ was either a very deliberate

prequel, or it was a notional prequel in which Wells began to develop the

ideas and images that later went into the novel. Either way,

I think we’re justified in treating the two stories as a whole:

H.G. Wells Mars.

So, what else do we learn about H.G. Wells Mars?

Well, first things first, the Martians that invade are not the only ones.

There are at least two other races of Martians, one of them quite surprising.

There is a winged race of Martians, as described by Mr.

Cave:

“The air seemed full of

squadrons of great birds, manoeuvring in stately curves.....suddenly something

flapped repeatedly across the vision, like the fluttering of a jewelled

fan or the beating of a wing, and a face, or rather the upper part of a

face with very large eyes, came as it were close to his own and as if on

the other side of the crystal.....The attention of Mr. Cave had been speedily

directed to the bird-like creatures he had seen so abundantly present in

each of his earlier visions. His first impression was soon corrected, and

he considered for a time that they might represent a diurnal species of

bat. Then he thought, grotesquely enough, that they might be cherubs. Their

heads were round, and curiously human, and it was the eyes of one of them

that had so startled him on his second observation. They had broad, silvery

wings, not feathered, but glistening almost as brilliantly as new-killed

fish and with the same subtle play of colour, and these wings were not

built on the plan of a bird-wing or bat, but supported by curved ribs radiating

from the body. (A sort of butterfly wing with curved ribs seems best to

express their appearance.) The body was small, but fitted with two bunches

of prehensile organs, like long tentacles, immediately under the mouth.

It was these creatures which owned the great quasi-human buildings and

the magnificent garden that made the broad valley so splendid. And Mr.

Cave perceived that the buildings, with other peculiarities, had no doors,

but that the great circular windows, which opened freely, gave the

creatures egress and entrance. They would alight upon their tentacles,

fold their wings to a smallness almost rod-like, and hop into the interior.”

These creatures are so peculiar that Mr. Cave describes them

first as bats, then as birds, and then as cherubs. But clearly,

they are non-human. The picture is of ribbed insectlike

wings, quite unlike those of bats, which roll up. The creatures

have humanlike round heads and large eyes, small mouths, small bodies and

two sets of tentacles beneath the head which are used for both land travel

and as hands.

It appears that they are most closely related to the ‘Big

Head’ ground hopping Martians, although it’s not at all clear what the

relationship is between the two kinds of Martians. We may be looking

at two different sexes, or at different life stages, or perhaps at two

separate but related species. Mr. Cave even speculates

that perhaps the ground hopping ‘big heads’ are the same creatures, who

have some means of detaching or removing their wings... A suggestion

that perhaps the wings themselves were artificial. However,

Mr. Cave never sees wings detached, and his ground hopping Martians seem

different enough that they are clearly not the same creature.

We presume that this race of winged Martians did not invade

Earth in

War of the Worlds because our gravity would be two much

for their wings. Mr. Cave saw his winged Martians as

the dominant species, but this may be due to his own vantage point, rather

than objective reality.

Of course, the winged Martians and the ‘big head’ Martians,

were not the only creatures on Mars that Mr. Cave observed:

“But among them was a multitude

of smaller-winged creatures, like great dragon-flies and moths and flying

beetles, and across the greensward brilliantly-coloured gigantic ground-beetles

crawled lazily to and fro.”

And elsewhere:

“.....beyond this was a

wide grassy lawn on which certain broad creatures, in form like beetles

but enormously larger, reposed.”

In short, what we have here is an insectopia, a land of giant

beetles and dragon flies, both flying and crawling along the ground.

The implication here is that the flyers themselves, given the structure

of their wings, are probably of insectoid descent, which further implies

that the ‘big heads’ are also insectoid in origin.

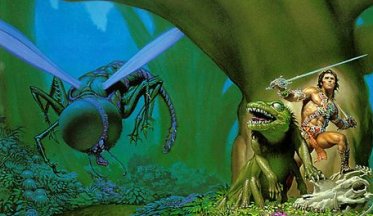

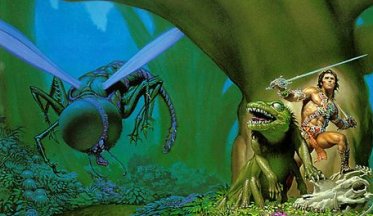

Barsoomian

Creatures on Wells Mars? Apes and Men, oh My!

There is, however, a very strange anomaly.

Mr. Cave observes ‘white apes’:

“He several times saw certain

clumsy bipeds, dimly suggestive of apes, white and partially translucent,

feeding among certain of the lichenous trees, and once some of these fled

before one of the hopping, round-headed Martians. The latter caught one

in its tentacles, and then the picture faded suddenly.”

This is very peculiar. What is an apparent, mammal-like, endoskeletal

vertebrate, particularly a semi-bipedal ape creature, doing here in an

ecology otherwise dominated by insects and the Martians we’ve seen.

There is no room, in this ecology, and no time for a single advanced ape-like

vertebrate to evolve. So where does it come from?

This is very peculiar. What is an apparent, mammal-like, endoskeletal

vertebrate, particularly a semi-bipedal ape creature, doing here in an

ecology otherwise dominated by insects and the Martians we’ve seen.

There is no room, in this ecology, and no time for a single advanced ape-like

vertebrate to evolve. So where does it come from?

Why describe this biped creature as an ape at all?

Although these tantalizing lines are all we have, we must assume that Mr.

Cave deliberately chose ‘ape’ rather than man, because its features, appearance,

movement were more apelike than manlike, despite its bipedal nature.

It is still remarkable though, and the ‘white apes’ of

H.G. Wells stick out like sore thumbs in his version of Mars.

One is tempted to speculate that here we may have the inspiration of Burroughs

Great White Apes of Mars.

But apparently, there are not just ‘white apes’ on Wells’

Mars, but something very like humans, as we see in this passage in Chapter

2 of the Second Part of War of the Worlds:

“Their undeniable preference

for men as their source of nourishment is partly explained by the nature

of the remains of the victims they had brought with them as provisions

from Mars. These creatures, to judge from the shrivelled remains that have

fallen into human hands, were bipeds with flimsy, silicious skeletons (almost

like those of the silicious sponges) and feeble musculature, standing about

six feet high and having round, erect heads, and large eyes in flinty sockets.

Two or three of these seem to have been brought in each cylinder, and all

were killed before earth was reached. It was just as well for them, for

the mere attempt to stand upright upon our planet would have broken every

bone in their bodies.”

These bipeds are definitely not Mr. Cave’s ‘white apes.’

They have round erect heads and large eyes in flinty sockets, suggesting

something very close to human. Little more can be told about

them, since obviously, they were killed before reaching Earth, their bodies

shrivelled utterly drained of fluid by the Martians, and now subject to

extensive decomposition and the shock of Earthfall. Whether

their flimsy spongelike skeletons were natural to their lives, or some

side effect of their drainage, shock of impact and decomposition is arguable.

Like the apes, these Manlike creatures are also the prey

of the ‘big head’ martians, and they’re just as inconsistent with the other

glimpses of Martian life that Mr. Cave spies through his egg.

In fact, these Martian humans and apes seem rather more

suggestive of Barsoom. One can, after all, be suspicious that

Burroughs may have read ‘The Crystal Egg’, but we can be almost sure that

he read War of the Worlds.

Like Burroughs' red and green men, and for that matter,

like the Kaldanes, Wells’ Martians are telepathic:

“I watched them closely

time after time, and that I have seen four, five, and (once) six of them

sluggishly performing the most elaborately complicated operations together

without either sound or gesture. I have a certain claim to at least an

elementary knowledge of psychology, and in this matter I am convinced-

as firmly as I am convinced of anything- that the Martians interchanged

thoughts without any physical intermediation. And I have been convinced

of this in spite of strong preconceptions. Before the Martian invasion,

as an occasional reader here or there may remember, I had written with

some little vehemence against the telepathic theory.”

Finally, let’s take a moment to consider the vegetation seen

in the Crystal Egg:

“There were also trees

curious in shape, and in colouring, a deep mossy green and an exquisite

grey, beside a wide and shining canal.... The terrace overhung a thicket

of the most luxuriant and graceful vegetation, and beyond this was a wide

grassy lawn....beyond that, and lined with dense red weeds....

among a forest of moss-like and lichenous trees... that it was these

creatures which owned the great quasi-human buildings and the magnificent

garden that made the broad valley so splendid. ... “

The red weeds, of course, provide another layer of identity

to link ‘The Crystal Egg’ with The War of the Worlds, suggesting

that Wells was using the same ideas for both, or perhaps that the two stories

were genuinely related.

“Apparently the vegetable

kingdom in Mars, instead of having green for a dominant colour, is of a

vivid blood-red tint. At any rate, the seeds which the Martians (intentionally

or accidentally) brought with them gave rise in all cases to red-coloured

growths. Only that known popularly as the red weed, however, gained any

footing in competition with terrestrial forms. The red creeper was quite

a transitory growth, and few people have seen it growing.”

But the descriptions of plants are not too different from

those that Burroughs himself uses, earthly plants with slightly unearthly

colours and shapes. Overall, the description of the fertile

valley is almost similar to that of the Valley Dor.

And finally, let me humorously quote this bit of Wells,

and have the reader think of Burroughs red men:

“The Martians wore no clothing.

Their conceptions of ornament and decorum were necessarily different from

ours; and not only were they evidently much less sensible of changes of

temperature than we are, but changes of pressure do not seem to have affected

their health at all seriously.”

Its almost tempting to see a shadow of influence there.

Did Burroughs initial fantasies involve a heroic Earthman turning the tables

on the Martians, perhaps rescuing a nude, telepathic captive princess from

the tentacled monsters of pure intelligence that preyed upon her race?

It’s almost tempting to see the bald Therns, cannibal intellectuals preying

on the red Martians much as Wells Martians must have preyed upon Wells

Marsmen, as a sort of stepped down version. The sumptuous garden

of the Valley Dor is more than a little reminiscent of the lush valley

seen by Mr. Cave, right down to the ‘white apes.’ And

of course, the Kaldanes of the later Chessmen

of Mars seem strangely reminiscent of Wells invaders. There

are peculiar similarities in the shades and descriptions of vegetation,

as between Burroughs and Wells, perhaps the one coloured the other?

This

is all just groundless speculation. I’m being mischievous,

after all, if Mr. Lupoff can claim that Arnold’s Gulliver Jones is the

inspiration

for John Carter’s Barsoom, I think that with equal merit, I can offer up

Wells’ Mars as an equivalent inspiration. It’s not at all certain

that Burroughs ever saw Gulliver Jones, but he almost certainly read Wells’

novel, and quite probably his short story. This

is all just groundless speculation. I’m being mischievous,

after all, if Mr. Lupoff can claim that Arnold’s Gulliver Jones is the

inspiration

for John Carter’s Barsoom, I think that with equal merit, I can offer up

Wells’ Mars as an equivalent inspiration. It’s not at all certain

that Burroughs ever saw Gulliver Jones, but he almost certainly read Wells’

novel, and quite probably his short story.

The real truth of the matter, is that all three, and for

that matter, other writers, were truly influenced by the astronomers

of their day, particularly Lowell and Schiaparelli. Their similar

visions of Mars as desperate dying worlds laced by canals and hosting human

and inhuman races is born of the science and prejudices of the day.

But what the hell, I didn’t put White Apes and Humans

on H.G. Wells Mars, he did that himself. And having done

so, we can’t say that perhaps there wasn’t some slight influence on Burroughs.

Barsoom may well include Wells’ Mars, or Wells’ Mars might have contained

the seeds of Barsoom.

Wellsian

Creatures on Barsoom: Kaldanes and Rykors, Oh My!

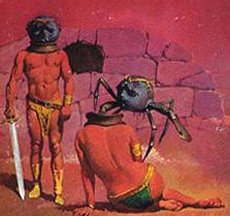

Now, take a moment and consider again Wells' descriptions

of his Martian invaders, (dubbed Sarmaks by George Alec Effinger in his

John Carter story, and dubbed Marvaders by certain fans, both names obvious

plays on Martian):

“They were huge round bodies-

or, rather, heads- about four feet in diameter, each body having in front

of it a face. This face had no nostrils- indeed, the Martians do not seem

to have had any sense of smell, but it had a pair of very large darkcoloured

eyes, and just beneath this a kind of fleshy beak. In the back of this

head or body- I scarcely know how to speak of it- was the single tight

tympanic surface, since known to be anatomically an ear, though it must

have been almost useless in our dense air. In a group round the mouth were

sixteen slender, almost whiplike tentacles, arranged in two bunches of

eight each. These bunches have since been named rather aptly, by that distinguished

anatomist, Professor Howes, the hands. .....their physiology differed

strangely from ours. Their organisms did not sleep, any more than the heart

of man sleeps. Since they had no extensive muscular mechanism to recuperate,

that periodical extinction was unknown to them. They had little or no sense

of fatigue, it would seem. On earth they could never have moved without

effort, yet even to the last they kept in action. In twenty-four hours

they did twenty-four hours of work, as even on earth is perhaps the case

with the ants.”

Meanwhile, we have Burroughs' Kaldanes from the Chessmen

of Mars, bodiless heads that ride headless bodies. The

Kaldanes inhabit a lost section of Barsoom called Bantoom.

The Rykors are humanoid bodies, apparently derived from some Barsoomian

primate and cross bred with Barsoomian humans to have only residual heads.

They appear, without Kaldanes, to be crawling creatures, able to breath

and move about, but barely able to feed themselves.:

“The heads were hideously

human and grotesquely inhuman at the same time. The eyes were

far apart and protruding. The nose scarce more than two parallel

vertical slits set vertically above a round hole that was the mouth....

the loathesome head rolled from the body and was now crawling on six short

spider like legs.... two stout chelae which grew just in front of

its legs and resembled an earthly lobster.... he extended a little

bundle of tentacles from the posterior part of the head....”

Wells discusses the internal structure of his Martians, essentially

giant brains with severely atrophied organs:

“The internal anatomy,

I may remark here, as dissection has since shown, was almost equally simple.

The greater part of the structure was the brain, sending enormous nerves

to the eyes, ear, and tactile tentacles. Besides this were the bulky lungs,

into which the mouth opened, and the heart and its vessels.

And this was the sum of the Martian organs. Strange as it may seem to a

human being, all the complex apparatus of digestion, which makes up the

bulk of our bodies, did not exist in the Martians. They were heads- merely

heads. Entrails they had none. They did not eat, much less digest. Instead,

they took the fresh, living blood of other creatures, and injected it into

their own veins. I have myself seen this being done, as I shall mention

in its place. But, squeamish as I may seem, I cannot bring myself to describe

what I could not endure even to continue watching. Let it suffice to say,

blood obtained from a still living animal, in most cases from a human being,

was run directly by means of a little pipette into the recipient canal....

The physiological advantages of the practice of injection are undeniable,

if one thinks of the tremendous waste of human time and energy occasioned

by eating and the digestive process.”

The Kaldanes, similarly, are brains with very little else

going for them, as Ghek tells us in Chessmen of Mars:

“Your brain is bound by

the limitations of your body. Not so ours. With

us, brain is everything. Ninety per centum of our volume is brain.

We have only the simplest of vital organs and they are very small for they

do not have to assist in the support of a complicated system of nerves,

muscle, flesh and bone. We have no lungs for we do not require

air...."

Wells discusses his Martian’s abandonment of bodies:

“Our bodies are half made

up of glands and tubes and organs, occupied in turning heterogeneous food

into blood. The digestive processes and their reaction upon the nervous

system sap our strength and colour our minds. Men go happy or miserable

as they have healthy or unhealthy livers, or sound gastric glands. But

the Martians were lifted beyond human frailties.”

The Kaldanes attitude towards bodies, is flatly contemptuous:

“When your body becomes

fatigued, you are comparatively useless. When it is sick, you are

sick. If it killed you die. You are the slave of a stupid mass

of useless flesh and bone and blood. There is nothing more wonderful

about your carcass than the carcass of a banth. It is only your brain

that makes you superior to a Banth, but your brain is limited by your body.”

And beyond that, Wells discusses their hypothetical origins

and evolution in very Kaldane-like terms:

“It is worthy of remark

that a certain speculative writer of quasi-scientific repute, writing long

before the Martian invasion, did forecast for man a final structure not

unlike the actual Martian condition. His prophecy, I remember, appeared

in November or December, 1893, in a long-defunct publication, the Pall

Mall Budget, and I recall a caricature of it in a pre-Martian periodical

called Punch. He pointed out- writing in a foolish, facetious tone- that

the perfection of mechanical appliances must ultimately supersede limbs;

the perfection of chemical devices, digestion; that such organs as hair,

external nose, teeth, ears, and chin were no longer essential parts of

the human being, and that the tendency of natural selection would lie in

the direction of their steady diminution through the coming ages. The brain

alone remained a cardinal necessity. Only one other part of the body had

a strong case for survival, and that was the hand, "teacher and agent of

the brain." While the rest of the body dwindled, the hands would grow larger.

There is many a true word written in jest, and here in the Martians we

have beyond dispute the actual accomplishment of such a suppression of

the animal side of the organism by the intelligence. To me it is quite

credible that the Martians may be descended from beings not unlike ourselves,

by a gradual development of brain and hands (the latter giving rise to

the two bunches of delicate tentacles at last) at the expense of the rest

of the body. Without the body the brain would, of course, become a mere

selfish intelligence, without any of the emotional substratum of the human

being.”

Meanwhile, the Kaldanes look forward to that same relentless

process of cerebation:

"From the beginning of

time, Nature has laboured arduously towards the consummation of this purpose.

At the very beginning, things existed with life, but with no brain.

Gradually, rudimentary nervous systems and minute brains evolved.

Evolution proceeded. The brains became larger and more powerful.

In us, you see the highest development; but there are those of us who believe

that there is yet another step - that some time in the future, our race

will develop into the super-thing, just brain. The incubus

of legs and chelae and vital organs will be removed.

The future Kaldane will be nothing but a great brain.”

Wells writes:

“We men, with our bicycles

and road-skates, our Lilienthal soaring-machines, our guns and sticks and

so forth, are just in the beginning of the evolution that the Martians

have worked out. They have become practically mere brains, wearing different

bodies according to their needs just as men wear suits of clothes and take

a bicycle in a hurry or an umbrella in the wet.”

Wells

refers to the Martians Machines, of course. But the Kaldanes

also have bodies that they put on and take off according to their needs,

wearing their Rykors like we wear suits of clothes. Wells

refers to the Martians Machines, of course. But the Kaldanes

also have bodies that they put on and take off according to their needs,

wearing their Rykors like we wear suits of clothes.

There are other similarities. Both races seem

strongly telepathic. Both reproduce asexually, the Wells’ Martians

by budding, and the Kaldanes by clone eggs laid by a single ‘King’.

Thus, with Wells’ Martians and Burrough’s Kaldanes, we

have two creatures that exhibit some physical similarities, but interestingly,

the deeper you go into their philosophies and evolution, the more identical

they become.

I speculated earlier, of course, that Burroughs might

well have taken some inspiration from Wells’ War of the Worlds,

but when it comes to the Chessmen of Mars, its impossible not to

believe that Burroughs had read Wells and that his Kaldanes were influenced

strongly by Wells’ Martians, to the extent that one is clearly related

to or descended from the other.

Clearly, the Kaldanes are Burroughs' adoption and modification

of Wells’ Martians. A tribute or borrowing if you will.

Thus, in any taxonomical sense, the two races are clearly linked.

Thus, we have an interesting bit of reciprocity.

H.G. Wells gave us white apes and humans on his Mars, as well as telepathy

and red and purple vegetation. Burroughs gives us evolved,

bodiless brains committed to cold intellect, wearing bodies like clothes.

Wells and Burroughs Mars now have at least five points of significant overlap.

We have come full circle, H.G. Wells’ Mars is on Barsoom.

Locating

Wells' Martians on Barsoom

But then, of course, we must ask... If Wells Mars

is Barsoom, then where on Barsoom are Wells Martians?

As always, geography rules. First

let us turn to descriptions of the geography that Mr. Cave sees in his

crystal:

“The view, as Mr. Cave

described it, was invariably of an extensive plain, and he seemed always

to be looking at it from a considerable height, as if from a tower or a

mast. To the east and to the west the plain was bounded at a remote distance

by vast reddish cliffs. These cliffs passed north and south -- receding

in an almost illimitable perspective and fading into the mists of the distance

before they met. He was nearer the eastern set of cliffs....

and passing up the valley exactly parallel with the distant cliffs, was

a broad and mirror-like expanse of water... a wide and shining canal.”

All right, first of all, this is real geography we’re talking

here. Mr. Cave’s view is from a high elevation, perhaps

hundreds of feet in the air, and clear in every direction.

The features he sees are entirely unambiguous, and more, they seem large

enough and distinctive enough to actually be able to locate.

This isn’t a case, for instance, of some guy who describes his home as

‘between a couple of low hills, with a winding river,’ rather, the geography

described should stand out like a sore thumb.

This is a large plain, likely several miles, or even dozens

of miles across, bounded on both sides by ranges of red cliffs.

These cliffs run roughly north to south, and are vast and immense,

so extensive that they vanish into the distance without apparent diminishment.

A river or canal runs down the centre. And obviously, we have

to be in the northern hemisphere, or no lower than the equator, because

we can see northern hemisphere stars from this valley.

Okay, so with a description like that, it should be hard

to miss. The first thought, of course, whenever we think of

a giant valley on Mars with high cliff walls, is obviously Valles Marinis,

but unfortunately, that immense canyon system runs east to west, not north

to south. Besides, on Barsoom, the Valles Marinis is well established

as being the site of the Toonolian Marshes for over half its length, and

as identified broken canyons and forest areas for the balance, the whole

area being well colonized by red man city states, so there’s no room for

Wells' Martians there.

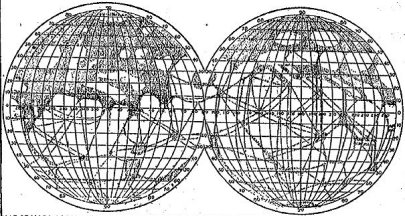

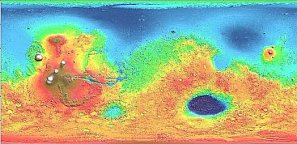

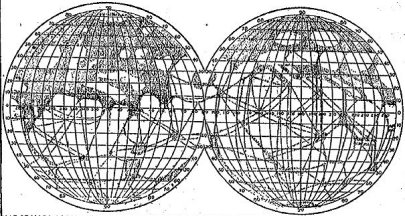

But here’s the truly interesting thing. If

we go and look at the MOLA topographic Map of Mars (never leave home without

it) we can actually find a little piece of Mars that fits our requirements.

http://ltpwww.gsfc.nasa.gov/tharsis/Mars_topography_from_MOLA/

If we take a look at the area of Mars known as the Tharsis

(the big brown mass with white spots) highlands, and if we look further

on the left side, between the immense central volcano Olympus Mons (the

big white spot), and the group of volcanoes collectively known as

Tharsis Montes (the central trio of white spots), we see a remarkable feature

resembling the spikes of a green trident sticking out from Tharsis.

This is the area of approximately 5 degrees latitude, and -140 degrees

longitude on the topographic map.

Now, if you are employing the internet version of the

Topographic map, you can actually zoom in on features. We can

see close up on this little trident feature, and we’ll see that the central

prong of the trident is actually a long straight cliff or mountain range,

moving roughly north/south (actually, slightly off true north, perhaps

northwest), as is the inner prong of the trident, closest to Tharsis.

Effectively, what we have here is a wide, deep, flat valley running and

opening between two roughly north/south straight cliff ranges.

In short, we seem to have found a far better geographical match than we

deserve.

And, of course, there is more. The Tharsis

mound is a highland region, the highest on Mars. Created by volcanic

uplift, it is well above the level of Barsoomian clouds.

As with mountain ranges on Earth, it’s a barrier to water bearing clouds

and water vapours. Thus, we can expect that water clouds and

moisture in the atmosphere, travelling through the air, encounters the

Tharsis barrier and can go no further. The clouds, bunching up like

a traffic jam, release their moisture as rain, or as streams and rivers

flowing down the Tharsis cliffs. And of course, where geography

shapes or guides the clouds and moisture into geographical corners and

cul de sacs you will get an accumulation of water.

Thus, our valley, bordered by two sets of cliffs, and

extending out from Tharsis, just south of the largest mountain on Mars,

is likely to be extremely well watered, with a healthy river or canal extending

out upon Barsoom. This explains the lushness, as compared to

most of Barsoom. It fits.

This area is in a largely unexplored portion of Barsoom,

the impenetrable and barren Tharsis highland acts as a barrier to exploration

from the east, and the western cliffs would also act to conceal it.

Cartographers or explorers would take the Western cliffs as the beginnings

of Tharsis, and not the sign of a valley. Only by entering

the mouth of the Valley would it be discovered.

And of course, there are a couple of collateral bits of

evidence. It is just north of the area we have provisionally identified

as the Kaldane’s Bantoom, and there is speculation that Wells Martians

may well be related to the Kaldanes.

Meanwhile, it is south of the area of Tempus Terra in

the northern edges of the Tharsis Mound, an area we have identified provisionally

as the Opal Sea and Hither lands of Gulliver Jones. In the

League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, of course, Gulliver Jones is

depicted as leading his Hither against the Martians. And geographically

at least, this seems feasible. Gulliver would simply have lead his

people around the edge of Tharsis, skirting Olympus Mons and then heading

straight down south.

Further, the redoubt or fortress of the Martians in Alan

Moore’s comic, is depicted as being inside an immense valley surmounted

by high cliffs on either side.... A valley mis-identified by some

as Valles Marinis, but whose appearance and description match may match

well enough to the trident valley we’ve identified on the topographic map.

Around on the other side of Tharsis, and comfortably back

in Burroughs, is the shallow end of Valles Marinis, hosting dried forested

portions of the Kaolian region, inhabited by at least a few species of

giant insect, notably the wasplike sith.

A final thought takes us back to Wells. Obviously,

the most benign spot for the Martians to launch their cylinders would be

from the Equator. And in order to construct their immense cannon,

they would need access to both vast amounts of energy and metals.

The volcanic Tharsis region would probably be the richest source of minerals

and geothermal energy on the planet, as well as a perfect launch site.

In short, not only is the geography of Wells’ Martian

region consistent with a bit of real geography on the actual Mars, but

it fits in quite well with Burroughs Barsoom, and with Alan Moore’s pastiche.

Evolution

of Wells' Martians on Barsoom

Here is the problem. How shall I put it?

Wells’ Martians seem biologically.... Inconsistent, on Barsoom.

Just as Wells’ apes and humans seem somewhat inconsistent on his Mars.

Here is the problem. How shall I put it?

Wells’ Martians seem biologically.... Inconsistent, on Barsoom.

Just as Wells’ apes and humans seem somewhat inconsistent on his Mars.

Think about it. Barsoom is wall to wall vertebrates,

everything has an internal skeleton, and all too often, way too many limbs.

There’s no shortage of bone and muscle, tooth and claw, and animal attributes

of every sort.

Meanwhile, the Kaldanes seem peculiarly out of place.

Obviously, they’re not vertebrates, they are not creatures of internal

skeletons. They possess insectlike legs and chelae.

Wells’ Martians with their soft round bodies, waving tentacles and rudimentary

organs seem similarly foreign to the Barsoomian ecology that we know.

The Wells’ Martian life we see in the crystal egg includes a flying species,

equally alien to Barsoom as we know it, with both tentacles and insectlike

legs, and further, most of the fauna we see through Wells crystal egg is

insect life, including gigantic beetles.

So where do these creatures come from?

Allan Moore, in his League of Extraordinary Gentlemen seems to have

Gulliver Jones and John Carter suggesting that Wells’ Martians are themselves

alien invaders to Mars. Essentially, that they’re foreign to

Barsoom. Moore obviously was wrestling, in part, with the same

problem that I am. The Wells’ Martians obviously seem foreign

to the ecological context of Barsoomian life. They don’t

seem to fit.

This theory is espoused by fans and Wold Newton writers,

and even by later day science fiction, such as the 1980's War of the

Worlds TV series which acknowledged Mars was a dead planet, and therefore

the invaders must be from farther out.

Well, the ‘alien hypothesis’ would solve a lot of problems,

but it doesn’t seem to hold up.

In Burroughs Chessmen of Mars, it seems clear that

the Kaldanes evolved as a sort of spider or insect. Specifically,

the Kaldanes co-evolved with their Rykors, and are definitely home grown

Barsoomians. This poses a problem.

The Kaldanes are all too clearly close relatives to Wells Martians.

If the Kaldanes are home grown, then so are Wells Martians.

Moreover, Wells himself, in both his “Crystal Egg” and

his War of the Worlds offers no suggestion that his Martians are

from anywhere but Mars. Quite clearly, their evolution is consistent

with his view of Mars as an ancient and dying world.

So on a strict reading of the canonical text, it seems

that they are stuck on and with Barsoom.

Alan Moore’s version of John Carter notwithstanding, the

Wells' Martians are local boys, just like the Kaldanes, Green Men, Red

Men, Hither, etc. It should be noted that John Carter, in Moore,

is bent on genocide. He’s united the entire rest of the planet with

the sole objective of wiping these creatures out, so it may make sense

that he refers to them as foreign invaders.

Wells gives no taxonomy or evolution for the Martians,

at one point, he warns that they could have evolved from creatures like

us, but in the "Crystal Egg," he seems to place them in an ecology dominated

by, or based on, insects, which suggests that they are ultimately some

form of insect life.

(On the logic that if the dominant lifeform is a big critter,

and your planet’s ecology is dominated by dinosaurs, then your dominant

critter is a dinosaur, or if your ecology is dominated by mammals, the

apex creature, Man, is probably a mammal).

So, what are we to make of this? The most

rational conclusion is that both the Kaldanes and Wells’ Martians are highly

evolved insect life forms. Well, evolution doesn’t just

produce one off's or happy monsters. If you had highly evolved

insect forms like Wells’ Martians and Burroughs' Kaldanes, you have to

have a variety of other evolved insects, effectively, several lines of

species, and even an insect ecology.

And in fact, this is what Wells’ shows us through the

"Crystal Egg." Interestingly, Burroughs also hints at other

highly evolved insects in the form of the Sith, a giant wasp of the Kaolian

forest, and the giant spiders of Ghasta in the southern hemisphere.

It’s hard to see how Burroughs' own giant insects, the Sith and Spiders

could have evolved in ecologies so dominated by vertebrates.

The conclusion must be that on Barsoom, there

was a parallel, isolated ecology of insect life, separate from the principal

ecologies of the vertebrate life. Where was this?

We can rule out the life around the polar ocean.

Although divided into three lobes or great seas, all of these ocean shores

would have been filled by fish and colonized by various sorts of lobe fin

fish. Thus, the oceans and their shores would be dominated

by vertebrate life.

The Hellas Basin, or Torquas Sea, had conditions far too

similar to the ocean shores, and was likely colonized by vertebrate life

moving overland from several directions. The ring of uplands

around Hellas was too gradual, and broken in too many places to prevent

infiltration from the species moving out from the shorelines.

Meanwhile, the Argyre basin, the site of the Valley Dor

and Sea of Korus, appears to have evolved as a plant utopia, eventually

producing carnivorous plants and the remarkable plant men.

In contrast, the insect utopia that produced the Kaldanes

and other remarkable forms, has to have four requirements:

1) It had to be remote from the other

areas and geographically distinct, there had to be physical barriers of

some sort to prevent Vertebrate life from invading and overwhelming the

insect forms, or vice versa (depending on which line of evolution was advancing

first and which had the most potential). In short, it had to

be literally locked off or isolated.

2) It had to be reasonably hospitable to life.

Obviously, we couldn’t be looking at a sparse desert, but rather, something

hospitable enough and stable enough that it could support a rich distinctive

ecology, and the opportunity for that ecology to refine and diversify itself

over millions of years.

3) But it had to have conditions sufficiently

different from those the vertebrates thrived in that they could not easily

colonize the region. In short, there had to be a certain

degree of ‘unfriendliness’ whether this be in the severity of seasons,

the distribution of water, the average temperatures, temperature extremes,

etc.

4) There has to be some geographical relationship

of sophisticated insect species now, even assuming that they diffused out

of their homeland. For instance, we don’t see Kangaroos

in England, nor do we see Bears in New Zealand. However, we

do see Kangaroos in New Guineau, which was once connected to Australia.

And we can trace Bears from Europe to Asia to North America, areas which

are or were all geographically related. By this same token,

we should be reluctant to assume that major insect species simply plopped

down randomly on the planet, or evolved in the regions that they are now

in. Rather, we should assume that they evolved in some central

or common region, and either remained there or traveled to their current

habitats in sensible ways.

In fact, the area of Mars most likely to satisfy all of these

conditions is roughly where we find the Kaldanes and Wells Martians.

Just south, in the shadow of the Tharsis bulge: This would

be a region, protected through much of its northern area by the Tharsis

cliffs and highlands, an impassable barrier for life on Mars. Directly

south is the South pole. On the East and West, this area is about

as far as you can get from either the Hellas or Argyre sea basins, both

of which are isolated by mountain and highland barriers. From either

of these basins, you would have to pass through a lot of extremely rough

and unforgiving desert and mountain territory to get to this region.

Further, the region just below Tharsis is itself broken up by low mountain

and highland barriers. In short, it is likely to be (and still

is in John Carter’s time) one of the most difficult and inaccessible regions

on the planet. So, it’s a perfect site for an ecological island.

However, the harsh and inaccessible conditions of the

surrounding terrain do not necessarily mean that this region itself is

harsh. It is likely to be well watered by drainage down from

Tharsis, and its edges are close enough to the polar seas that primitive

life might well make it into the region from time to time, depending on

climactic conditions. Such life might well find a potential

garden of Eden with all the requirements to support a blooming ecology.

Of course, garden of eden is a relative term.

Normally, for life, Martian nights and days elsewhere are moderated by

the polar ocean or the south hemisphere seas. These large bodies

of water regulate climate by soaking up heat during the day and releasing

it during the night, much as oceans and seas do on Earth. Thus,

in the lowland regions of these areas, the climate is pretty steady, from

day to night and from summer to winter. The temperature changes,

but the fluctuations are not savagely extreme. On the

other hand, without a large body of water to regulate temperatures, fluctuations

become extreme, days are sweltering, nights are freezing, summers are blistering,

winters are savage. I have personal experience of this, having

grown up on the Atlantic coast and moved out to the Canadian prairies.

One could only expect that conditions on Barsoom beneath Tharsis, well

away from any moderating body of water, would be more extreme.

These strong fluctuations in temperature would certainly act as a barrier

to more advanced vertebrates, who were more adapted to relatively stable

climates. The temperature ranges would get them, again and

again. Even for desert adapted vertebrates more used to temperature

ranges, the large amounts of moisture and water in the region would combine

with temperature to form a barrier. It wouldn’t keep the vertebrates

out of the region forever, but it would hold them off for a good long time,

allowing life in this region to develop in its own way.

Finally, it makes sense in terms of the dispersal that

we are familiar with. The Kaldanes of Bantoom are still in

or near the homeland. The Wells’ Martians have clearly

moved out, occupying a valley once bordering an ancient sea, but still

hugging the line of the Tharsis bulge. The Sith of the Kaolian forest

has also followed the Tharsis bulge, moving even further. Meanwhile,

the spiders of Ghasta have spread within the southern hemisphere, not too

far from the homeland. The species distribution either diffuses

overland through the southern hemisphere, or follows the outlines of Tharsis.

It works.

Here we might expect Barsoomian insects to evolve into

sophisticated and gigantic forms over long ages, and to even develop sophisticated

brains and societies. Of course, the Insect Utopia would

not endure indefinitely on Barsoom.

Sooner or later, the vertebrates would evolve to the point

where their species would invade the insect regions. Among the earliest

invaders might have been the Great White Apes and Banths who seem ubiquitous

across the planet. We note that in Bantoom, the Rykors have

long been incorporated into the Kaldane’s evolution and society, and that

they are familiar with the depredations of Banths (although practically

no other vertebrate animal intrudes). Even in the Wells’ Martians

secluded valley, white apes appear. Life adapts, evolves and

expands. It is inevitable that life forms would spread to every

point they could reach, and as they grew more sophisticated and adaptable,

their reach would expand. Eventually, the insect utopia would

be breached.

The result would be a mass extinction of much of the sophisticated

insect life. It’s likely that the insects of Barsoom,

as on Earth, simply had less potential and more handicaps than the vertebrates.

With more potential to exploit, the vertebrates would inevitably out-compete

and wipe out most insects. There’s also the comparative sizes of

the two competing ecologies. The Insect Utopia occupied at

most, a fertile crescent in the shadows of Tharsis and some hinterlands.

A few million square miles at most. In comparison, vertebrate

life dominated the polar sea shorelines and lowlands as well as the Hellas

basin. Their territory was tens of millions of square miles.

Competitive pressures were stronger in the diverse and manifold vertebrate

regions, their species were more adaptable and robust.

It would be similar to that experienced when old world

fauna invaded through North America into South America. Many

South American species, with less potential, from a smaller ecological

area and therefore less robust, were simply wiped out.

Pockets of insect life would survive in isolated regions,

of course. The heartlands of insect utopia would provide the

best refuges for insects and the greatest challenges for vertebrates.

The more robust insects would fight back against the vertebrate invasion,

surviving in the new ecology and even spreading into vertebrate regions,

as we see with the spiders and sith. The vertebrates would

incorporate these new insect species into their ecology, just as, in certain

areas, vertebrates would be incorporated into the bastions of the remaining

insect ecology.

It would be at this point that the Kaldanes and Wells

two races of Martian would split off from each other, maintaining their

own isolated ecological enclaves. The Kaldanes clearly began

to enter into symbiotic relationships with host vertebrates, suggesting

that their areas had become a mixed insect/vertebrate ecology.

The Wells’ races of Martians, in contrast, appeared to have remained much

further in the core of the remaining pure insect ecology. Without

the limitations of symbiotic vertebrates, the big heads became even bigger,

doubtless using their mental faculties to best advantage. The

big heads eventually began to prey on vertebrates, but vertebrates remained

a relatively small part of the ecology in these areas. The

flyers likely dominated the cliffsides of Tharsis.

As Barsoom began its long decline, and the seas vanished,

it appears that the big heads and flyers left the shadow of Tharsis, whose

environment had begun to deteriorate, and moved to a sheltered valley adjacent

one of the former seas. They were clearly seeking a more stable

geographical area, and a watered river or canal valley bounded on both

sides by long impenetrable cliffs would be both eminently defensible and

feature extremely stable climate.

A

Little Problem

There is one small obstacle to unifying Wells and Burroughs

Mars. Wells’ Mars had themselves quite a loud and nasty invasion

of Earth, round about 1898-1899. Neither John Carter

nor any other of Burroughs protagonists, in the series, ever actually refer

or say anything that could be construed as a reference to this invasion.

This has got to be a pretty big gap. After

all, one can imagine that if Martians with tentacles and crap like that

had trashed England in their giant machines, this would have certainly

coloured views for a long time. John Carter’s arrival

on Barsoom was around 1867 or thereabouts, so obviously, wouldn’t have

been influenced by the War of the Worlds.

But why on Earth would Gulliver Jones or Ulysses Paxton

want to go there, given that their journeys were taking place well after

the Martian invasions, when presumably everyone knew what the Martians

were like?

In the case of Jones, we might make an excuse or two for

him, his adventures were published in 1905, so they occurred before this.

It is possible that his journey to Mars occurred before the War of the

Worlds.

On the other hand, Paxton goes to Mars during WWI, around

1917, or nearly twenty years after the Martian Invasion. Surely

he’s got to suspect that its not all Red Princesses and Green Men.

But there’s never a mention or a hint, not even so much

as an awkward silence. That’s a bit hard to swallow.

Of course, we can offer some fairly speculative explanations.

We can assume that the world was not so tightly woven

together in those days. Thus, for America and for Europe, England

was a remote far off country. In 2001, the entire world watched

the World Trade Centres fall. But 1899 is a different country, communication

is slower and less immediate. The telegraph could splash the

news of the Martian invasion of England onto front pages in America, but

the information will come through laboriously slow as a series of dots

and dashes, there will be no photographs, descriptions and reports will

be terse and second hand. There won’t be front page photos,

live television, or endless camcorder records. At best, you’ll

get a few badly drawn sketches based on secondhand information.

In short, for much of the world, the impact of a Martian

invasion of England, might not have the same immediate and worldwide impact

as a major terrorist attack or disaster like the Tsunami in the modern

day.

The world of 1899 was far more accepting of the notion

of life, of intelligent life, on other worlds, so that would not necessarily

have been as shocking. Meanwhile, a number of factors would

have limited the shock and acted to restore complacency. The

invasion seemed confined to England, and the invasion was remarkably short

lived, only a matter of weeks. Finally, the Martians simply were

unable to cope with Earth’s conditions, clearly shutting the door on the

whole matter.

So, one might imagine a stir for a year or two, but eventually,

people would settle down, get on with their lives and forget about it.

Particularly when no further invasions are forthcoming. I imagine

the English would still be somewhat traumatized, but John Carter, Gulliver

Jones and Ulysses Paxton are all Americans.

One thing which would certainly insert itself into public

consciousness is the fact that there are humans, or humanoids on Mars,

in addition to the ugly Wells creatures. So, doubtless all

sorts of fancies or fantasies would be spun to the public to explain both

humans and the failure of the big heads to return.

Of course, this might explain the failure of the War

of the Worlds to create a big long lasting ripple. But still,

there must have been some awkward moments between Carter and his nephew.

Indeed, if we’re willing to read generously into Burroughs

canon, one very peculiar fact does stand out. There are, awkward

pauses for which there is no apparent explanation.

Consider, according to these timelines:

http://www.xenite.org/edgar_rice_burroughs/barsoom_chronicles/timeline.html

http://www.erbzine.com/mag0/0051.html

John Carter goes to Mars originally in 1866, returns

to Earth in 1876 and leaves for Barsoom again in 1886, after which Burroughs

finds his manuscript for Princess of Mars.

In 1898, John Carter returns to visit Burroughs and tell

him of his and his son’s adventures. This is just before the

War of the Worlds, which likely takes place sometime between 1898

and 1900 (call it 1899). So obviously, the conversations and

discussions between them are not tainted by the War of the Worlds.

But then, following the War of the Worlds, there

is a twenty seven year gap to John Carter’s next visit in 1925.

Well, that’s a huge awkward silence, is it not? It seems

a cold chill has descended between Earth and Mars for an entire generation,

possibly as an indirect result of the Martian invasion?

The next contact is five years later, via Paxton and the

Gridley Wave, in 1935. And ten years later, in 1940, there

is another Gridley Wave transmission from Paxton.

Now, here’s something very peculiar. Despite

the clear fact that Burroughs is receiving Gridley Wave transmissions in

the '30s and '40s, there is no official contact between Mars and Earth

until the Moon Maid reports it in 1967.

Again, there’s an inexplicable cold radio silence for

thirty years, where the channels seem open, but Earth isn’t officially

willing to receive. Is this further evidence of fallout of

chill from the War of the Worlds?

Or how about this: Although Burroughs

has received the Princess of Mars manuscript as early as 1886, and

hears the next three stories by 1898, it isn’t until decades have passed

before Princess of Mars is published in 1912, with the three succeeding

stories coming out of the next decade.

Now, it may be curious why Burroughs does not publish

John Carter’s manuscript between 1886 and 1898, but perhaps he feels no

need to do so. It’s an odd curio. However, in 1898, he’s

now in possession of no less than four manuscripts.... So why

does it take well over a decade to publish them?

Or for that matter, Arnold’s Gulliver Jones may

well take place prior to 1898, but is not published until 1905. Why

the delay?

Because, in 1899, the Martian invasion occurs, and after

that, adventures of humans on Mars are literary poison. The public

has well established ideas of what Martians look like, what Mars is like,

and what the relationship to earth is, all horrible, and simply will not

look at anything that deviates from those ideas.

Over time, the idea of humans on Mars percolates through

of course. The shock of the invasion wears off.

The trauma diminishes, and slowly, people become more open.

As the ‘big head’ Martians become trite and cliched, people become more

and more fascinated by the tantalizing evidence that there are indeed human

martians, whose remains were found in the invaders capsules.

The ‘literary chill’ is so profound that it takes Arnold

six years to publish Gulliver, which essentially merely tests the

waters and is unsuccessful. Burroughs waits a full thirteen

years for the sting of the Martian invasion to fade before offering up

John Carter’s manuscript, and only after it is successful, does he release

the others, one at a time, all of the time, carefully avoiding the very

impolitic fact of the invasion.

Only after the manuscripts success is confirmed, does

John Carter dare to return to earth to carry on his relationship with is

nephew. How John Carter determines that the manuscripts have

been successful is another question. He may simply have decided

to wait a good decade before checking things out.

Despite the thawing of the literary and social chill,

of course, there is a political chill. Thus gridley wave radio contact

between the two worlds is ignored by Earth governments and scientists for

a generation between 1935 and 1940 and 1967.

And of course, the only effort to actually go to Mars

is by Carson, who is a bit of a daredevil in 1930. He

may not even have been born at the time of the Martian invasion, so he’s

clearly not deterred from wanting to go and check the place out.

Indeed, he’s probably intrigued by the mystery of the ‘big heads’ failure

to follow up their invasion, and the reports of humans on Mars.

Earth governments have no interest whatsoever in sending

a ship to that clearly hostile world, no sense looking for trouble,

until well after peaceful communication is established in 1967, and the

‘Big Heads’ are confirmed to be long gone.

Essentially then, it might just be possible to actually

read in the ‘big awkward silences’ some hints that Wells' War of the

Worlds occurred on Burroughs Earth, and has resulted in a certain delicacy

and avoidance around the topic.

Finally, and this is obviously conjecture on my part,

the War of the Worlds may well have had an impact on Burroughs Earth.

In the Moon Maid, Burroughs writes that the first world war continued,

almost uninterrupted, off and on until the 1960s on Earth.

In our world, of course, there was an almost 20 year gap between the two

world wars, to be followed by a cold war through the '60s.

In Burroughs world, the war seems to have been an almost continuous, generations

spanning conflict, with perhaps shorter periods of peace and stability.

Wells, in War of the Worlds, writes that human inventors found Martian

machines to be fertile inspiration for their inventions. The

implication is that the alien technology of the Martians has boosted Earth

technology in some respects.

Wells, in War of the Worlds, writes that human inventors found Martian

machines to be fertile inspiration for their inventions. The

implication is that the alien technology of the Martians has boosted Earth

technology in some respects.

At least some of those boosts would be in military technology,

the Martians were using poison gas, for instance, fifteen years before

humans would.

So, is it possible that the influx of useable Martian

technology helped to prolongue and extend Earth’s World War, so that instead

of a couple of short, sharp, brutal conflicts, Burroughs world ended up

in a long dragged out affair? Something to think about.

John

Carter's War of the Worlds

Of course, Burroughs and Wells were dealing with copyright

issues in their day, and as working writers, knew better to step on each

others toes. They would have each recognized that they were

doing radically different things with their Mars, and the others versions

of Mars would not have been all that compatible with what they were doing,

or what they were interested in doing.

But, not so the modern day, where a couple of reputable

professionally published writers of literary reputation have boldly stepped

into the fray and shown John Carter fighting the War of the Worlds on Barsoom.

I’m frankly of mixed minds on this stuff.

The minute you step away from canonical sources, you enter dangerous territory.

In particular, its dangerous to mix media, to go from novels to comics

to movies, as each tends to modify the material. This is precisely

where so much of the Wold Newton stuff goes off the rails, by mixing media

and failing to distinguish canonical and noncanonical material.

But in this case, I think that without fully accepting

the George Alec Effinger and Alan Moore stories, we should acknowledge

that these are both writers of high literary and popular reputation, who

in these and other works exhibit a well known fidelity to their source

materials, and whose pastiches are commercially and professionally published.

So, call it semi-canonical. Something we can play with, and

even, with reservations, accept.

Effinger opens up John Carter’s War of the Worlds with

the beginning of the story. In short order, we’re shown Carter

at peace in Helium, the discovery of the kidnapping of Dejah Thoris, his

travel to the formerly unknown land of the Sarmaks where the big gun is

in preparation... And after that, it offers only hints and outlines,

while reassuring us that everything turned out in the end and the threat

is ended.

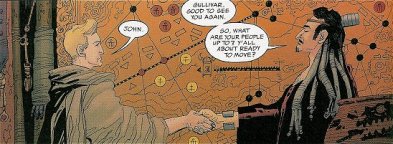

Alan Moore, on the other hand, delivers us the end of

the story. John Carter, as the Warlord of Mars, has put together

a worldwide coalition of races and nations to obliterate the Sarmaks from

existence. Gulliver Jones is part of John Carter’s alliance.

There is a clear reference to Dejah Thoris, and unpleasant things having

happened to her, but its not clear whether she’s living or dead, free or

still a hostage, healthy or injured. The Sarmak have

clearly been pushed back through their valley, to their final redoubt,

and as the walls of their fortress are breached, and their race slaughtered,

they launch their final capsules towards Earth.

There are numerous small discrepancies in Moore’s comic

from the canonical sources: Gulliver flies on his carpet, but in the novel,

it wraps around him like a cocoon, the Thoats have clawed feet rather than

nailless hooves, Gulliver’s look and dress are reminiscent of Laurence

of Arabia, while John Carter’s look and costume seem to be some hybrid

between British officer and oriental potentate. They’ve both

become rather English.

But despite this, we can at least reasonably accept that

George Alec Effinger has given us the beginning, and Alan Moore has provided

us with the end, of the story that Edgar Rice Burroughs never told, the

missing saga of John Carter’s life. The middle, of course,

remains unknown and unknowable.

And here, I will leave it to the reader....

|

. . .. . .

. . .. . .

![]()

![]()