It was a favourite even in the early days of

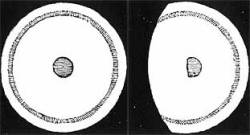

telescopes, for the 17th century astronomers. Fontana made

the first sketch of the red planet. Huyghens in 1666 determined the

length of the Martian day, followed in the same year by Cassini’s description

of the polar caps.

Fontana sketches and Cassini's Mars

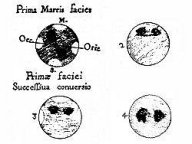

Huygen's Mars

Oddly red in colour, astronomers could train their telescopes

upon it and make out actual surface features, and more than that, they

could observe changes, marking the progress of seasons.

They could discern the white polar caps and watch them swell and retreat

over the Martian year good evidence there for ice of some sort, almost

certainly water ice. They could occasionally spot clouds,

and see when dust storms obscured the entire surface of the planet, clear

evidence of a reasonable atmosphere.

They could make out light and dark features that seemed

remarkably consistent, and yet, changed slightly over time and with seasons.

The equatorial region seemed the source of a dark thick, dark erratic band.

The upper hemisphere was somewhat light, the southern hemisphere somewhat

dark. It was speculated at first that the upper hemisphere

was a continent, the darker areas were seas.

Later, around 1890 evidence of water waned, perspectives

changed and the notion arose that the light areas were desert, and the

dark areas the marshy remnants of dried seas. The conception

of the Martian atmosphere changed, due to the infrequency of clouds and

dust storms, the air was thought to be relatively thin.

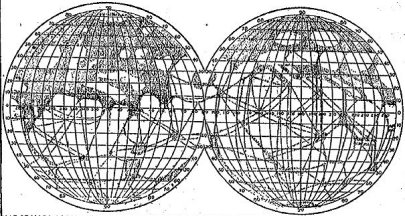

Notwithstanding this interpretation, it is remarkable

how the maps made were quite close to telescope photographs, and even of

the maps drawn from the space probes. Genuine features, including

Syrtis, Hellas, Argyre and the poles were accurately described.

Over centuries, astronomers proved themselves by giving us reasonably accurate

broad descriptions of the planet. (Some degree of caution must be

used with maps of this era, since due to astronomical convention, they

were done upside down, with north and south reversed) Where they

fell off, was with fine details, like the canals....

The earliest sketches or drawings of Mars which appear

to show canals actually date back to 1840, and appear again independently

in 1864, though they were not called canals then.

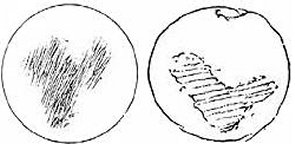

Schiaparelli was the first astronomer to identify the

illusory features as Canals, in 1877. Producing the first accurate

(for its time) detailed map of mars. This was also the

year that Mars two moons, Phobos and Deimos were discovered.

So there was a kind of ‘plausibility by association.’ If one

new feature (the moons) were accepted, why not the other (the canals).

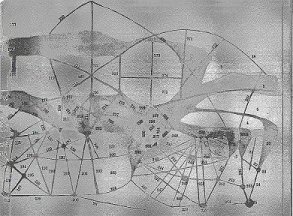

Schiaparelli's

Mars 1888

Schiaparelli repeated and elaborated on his observations

two years later in another close approach in 1879, eventually identifying

some sixty distinct canal like structures. He called them ‘Canali’

or channels, which did not necessarily mean they were products of intelligent

life.

But on the other hand, he refused to rule out intelligence

and failed to propose any other explanation. He felt that they

might be a system for distributing water from melting polar snows to other

parts of the planet, a theory which naturally inspires thoughts of intelligent

origin. In other words, Schiaparelli was being coy, describing

structures which were highly suspicious and suggestive of life and intelligence,

but at the same time, reluctant to speculate as to their origins, refusing

to rule intelligence out, or to embrace it.

Unfortunately,

for the next several years, no one else saw canals on Mars.

The next observations were nine years later, by a pair of Astronomers.

But indeed, they were observed only infrequently after that.

Lowell writes in 1895 that the number of people who had seen and described

the canals could be counted on one hand. The astronomy community

capable of making those observations was small, but not that small.

Unfortunately,

for the next several years, no one else saw canals on Mars.

The next observations were nine years later, by a pair of Astronomers.

But indeed, they were observed only infrequently after that.

Lowell writes in 1895 that the number of people who had seen and described

the canals could be counted on one hand. The astronomy community

capable of making those observations was small, but not that small.

This was also an age of canals on Earth. The Suez

Canal had been built in 1860, and the French had begun an effort at central

American canal to unite the Pacific and the Atlantic. Canals,

even fairly large ones had been built in the United States and Canada,

France and England, so they were well known, but the new giant Panama and

Suez canals were literally an order of magnitude greater, transforming

continents. The notion that there were similar works

on Mars came naturally.

Nevertheless, the fact that they were being spotted independently

by a handful of observers, the fact that they preceded their official discoverer

by a generation, and the fact that they were quite consistent among those

who observed them, suggested that there was actually something real there,

so the scientific and the popular communities generally accepted their

existence. Even the failure of these canals to appear in most

photographs was not damning, particularly as at least a few photographs

under perfect conditions, seemed to show some of them.

Part of this acceptance lay in the fact that observation

conditions were often imperfect, due to inclination, Mars was best observed

from the southern hemisphere. The power of telescopes, and

the weather conditions and local conditions of observatories varied widely.

So no one took it all that seriously if features so subtle were not universally

recognized.

Another part of this was that Mars orbits and Earth’s

orbits were quite different. Close approaches varied from fifty

million miles to an optimum of about thirty five million. Only about

every several years were the planet’s lined up at closest approaches.

Following Schiaparelli, the best oppositions occurred in 1892 and 1894,

1907 and 1909 and 1924 and 1926.

The first two sets of dates are particularly critical.

1892 and 1894 were the crucial times during which Percival

Lowell made his critical observations and wrote his popular book

on Mars, a book that Edgar Rice Burroughs undoubtedly read and was

influenced by. It was also likely this book and these same

series of observations

that brought Mars into prominence and inspired both Arnold’s and Wells

respective books about Martians. Meanwhile, 1907 and 1909 would have

put Mars prominently in the news once again, only a few years before Burroughs

wrote A Princess of

Mars.

The astronomer, Pickering, in 1892, came up with the suggestion

that canals were not truly watercourses. They were too thick for

that, the smallest were estimated to be ten to twenty miles in width, the

largest were 150, rather. He thought instead they were bands

of vegetation, perhaps fed by watercourses. But the actual canals

or Martian rivers were too small to see, we were observing the vegetation

that grew up around them. This neatly explained why some different

numbers of canals were seen... Some simply would not be in season

at some times. Several other noteable astronomers wrote of

Mars canals, including Kayser, Proctor, Green, Dreyer and Flammarion.

Meanwhile, there was a picture being built up of Mars.

There was a growing consensus in the 1892-1894 period that its small size

and lack of reflections indicated that there were no major areas of deep

water on the planet. The lighter area of the north, and in

the south, were taken as evidence of continental structure, perhaps worn

smooth and reduced to desert. The dark central band which waxed and

waned with the seasons was assumed to be a dry sea bed. Vegetation

living off residual moisture in the sea bed was considered a likely explanation

for the seasonal changes.

Mars, astronomers decided, was a dry planet having lost

most of its waters to space or absorbed by the planet’s chemical processes.

The lack of clouds and the difficulty in observing signs of atmosphere

lead to the belief in a very thin and perhaps slowly vanishing atmosphere,

perhaps comparable to the mountain regions of Earth. It was

believed to be a very old world.

In short, this was hardly different from the Barsoom that

Burroughs described. He was building his world based on the

state of the scientific art of his time, and indeed, that persisted for

decades after. And for that matter, this was the science

picture of Mars that anchored both Wells' War

of the Worlds and Arnold’s Gulliver

Jones of Mars. So with respect to the Arnold/Burroughs

thing, at least one source of similarity was that they were both drawing

on the same picture of Mars present and past.

These theories made Mars a world unlike any other in the

solar system. It was a world with a past. The moon had always

been a rock, we couldn’t tell what was under Venus clouds, and the other

planets seemed stolid and timeless. But Mars had a past, a

past that included continents and oceans and thick air and possibly life.

It had been a young world like Earth. And now it was an old world,

the seas dried up, the continents worn away, endless encroaching deserts

and life clinging on in drying sea beds. It was a vision both

romantic and evocative, disturbing in its hints of our own fate, tragic

or disquieting to contemplate life and intelligence trapped on that dying

world. Mars, shared with Earth a uniquely metaphysical

distinction of being world with history written upon it.

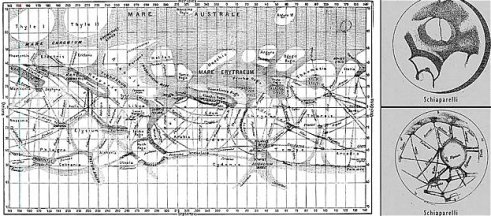

Canals really came into their own with Percival Lowell,

who built on Schiaparelli’s work. Through painstaking observations,

Lowell built up a detailed

map, identifying over 180 canals (subsequent astronomers

eventually charted over 500) including most of those seen by Schiaparelli.

His observations, while more extensive, were in general agreement with

his predecessors. Lowell formed a theory of a dying world,

its seas dried up, its continents worn away. The canals, he

concluded, were artificial structures created by the inhabitants of Mars

in order to draw moisture from the poles, or from the remnants of the Martian

seas.

Lowell's

Mars

The canals, as described by Lowell, Schiaparelli and others,

were peculiar features indeed. For the most part they were

absolutely straight, adjusting only for curvature of the planet.

Their lengths varied from 250 miles to 4000 miles. They often joined

one another, like spokes in the hub of a wheel, though angles varied.

Their thickness was uniform along their length, varying from 20 mile thick

small canals, to giants 140 miles thick. There were double

canals, structures running parallel to each other. There seemed to

be triangular structures joining canals, similar to river deltas.

Their ‘oasis’ or joining points defied explanation.

In short, Lowell’s theory that they were the work of intelligent

beings was regarded as wild by other astronomers, not because it flew in

the face of data. In fact, the work of intelligence was quite

a good explanation for what Lowell and others were recording. But

the conservative minds of the scientific community simply argued that there

might be other explanations for these structures.... Like vegetation.

Their problem with Lowell was that they merely considered him premature.

Nevertheless, Lowell’s speculative book was read widely,

and almost certainly by Burroughs himself. Lowell’s romantic

depiction of a dying civilization, struggling desperately to survive by

building a network of canals, finds its way into Burroughs.

A link to the book, now available on the net can be found at the Bibliomania

site:

Indeed, at the conclusion of his discussions, Lowell dwells

at length on the nature of the Martians. The passages are worth

quoting here,

for the echoes of John Carter’s own experiences:

“We may, perhaps, in conclusion,

consider for a moment how different in its details existence on Mars must

be from existence on the Earth. If we were transported to Mars, we should

be pleasingly surprised to find all our manual labor suddenly lightened

threefold. But, indirectly, there might result a yet greater gain to our

capabilities; for if Nature chose she could afford there to build her inhabitants

on three times the scale she does on Earth without their ever finding it

out except by interplanetary comparison. Let us see how. As we all know,

a large man is more unwieldy than a small one. An elephant refuses to hop

like a flea; not because he considers the act undignified, but simply because

he cannot bring it about. If we could, we should all jump straight across

the street, instead of painfully paddling through the mud. Our inability

to do so depends upon the size of the Earth, not upon what it at first

seems to depend, on the size of the street.

As the reader must also note, the

deduction refers to the possibility, not to the probability, of such giants;

the calculation being introduced simply to show how different from us any

Martians may be, not how different they are.

Mars being thus old himself, we

know that evolution on his surface must be similarly advanced. This only

informs us of its condition relative to the planet's capabilities. Of its

actual state our data are not definite enough to furnish much deduction.

But from the fact that our own development has been comparatively a recent

thing, and that a long time would be needed to bring even Mars to his present

geological condition, we may judge any life he may support to be not only

relatively, but really older than our own.

Quite possibly, such Martian folk

are possessed of inventions of which we have not dreamed, and with them

electrophones and kinetoscopes are things of a bygone past, preserved with

veneration in museums as relics of the clumsy contrivances of the simple

childhood of the race. Certainly what we see hints at the existence of

beings who are in advance of, not behind us, in the journey of life.

To talk of Martian beings is not

to mean Martian men. Just as the probabilities point to the one, so do

they point away from the other. Even on this Earth man is of the nature

of an accident. He is the survival of by no means the highest physical

organism. He is not even a high form of mammal. Mind has been his making.

For aught we can see, some lizard or batrachian might just as well have

popped into his place early in the race, and been now the dominant creature

of this Earth. Under different physical conditions, he would have been

certain to do so. Amid the surroundings that exist on Mars, surroundings

so different from our own, we may be practically sure other organisms have

been evolved of which we have no cognizance. What manner of beings they

may be we lack the data even to conceive.”

And there we have it folks. John Carter’s astonishing

leaps. The detailed portrait of an ancient world with an ancient

civilization technically more advanced than our own. And of

course, the glimmers of the Green Men appear in speculations of Martian

giants three times our size, of nonhuman nature. The outlines

of Barsoom can be found in Lowell.

The canals on Mars were a done deal. I have

a book on astronomy, originally published in 1922, reprinted in 1939, which,

despite noting that the canals were still controversial and that some astronomers

disputed their very existence, states that “the canals, as far as

they are considered to be line like markings, have been completely verified.”

![]()

![]()