A Lost Freedom Classic

. . . Found!

by Wally

Conger

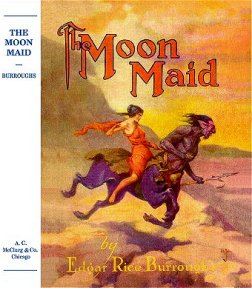

When I was 13, my parents

gave me a copy of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ The

Moon Maid for Christmas.

They did it for two reasons.

First, they knew I loved Burroughs’ Tarzan

and

John Carter of Mars

books. Second, they knew I loved science fiction.

I thanked them for the gift.

Then I tossed it into the back of my closet, unread.

I did it for two reasons.

First, neither Tarzan nor John Carter was in the novel. Second, it was

called The Moon Maid, which stirred up images of that awful Moon

Maid character from the Dick Tracy comic strip.

That old copy of The Moon

Maid is probably sitting in some Salvation Army thrift store today.

But I’ve been feeding a Burroughs binge lately, rereading the Tarzan stories

and Carter’s adventures on Barsoom. And last week, looking for something

I hadn’t read yet, I finally picked up a new copy of The Moon Maid.

What I missed at age 13 —

and only now discovered at 50 — is not just a sci-fi classic but a pioneering

novel of freedom and resistance that stands splendidly alongside Ayn Rand’s

Atlas

Shrugged, Ira Levin’s This

Perfect Day, and, most recently, Vin

Suprynowicz’s The Black Arrow.

The Moon Maid has a remarkable

history. It consists of three consecutive novellas. The second was actually

written first, in the spring of 1919, shortly after the Bolshevik revolution.

Burroughs titled this story

“Under the Red Flag.” Set a century or two in America ’s future, it told

the tale of Julian James, born in a Bolshevik dystopia and living in the

31st Commune of the Chicago Soviet. Lantski Petrov is president of the

United States , and Otto Bergst is the new commander of the Red Guard at

Chicago .

As a piece of anti-Communist

fiction, “Under the Red Flag” predated Rand ’s We

the Living by 17 years and Orwell’s Animal

Farm by almost three decades. But in 1919, no one would publish

it. The story was rejected 11 times by periodicals as varied as the Saturday

Evening Post and the Argosy

All-Story line of pulp magazines, which had already published Burroughs’

enormously popular A

Princess of Mars (1912), Tarzan

of the Apes (1912), and At

the Earth’s Core (1913), among others.

The unpublished story was

filed away, but not for long. Burroughs was a businessman, and he decided

he had to salvage something from his time spent writing “Under the Red

Flag.” During a single day in 1922, he rewrote the yarn. It was still set

in the 22nd Century, but the Bolsheviks were turned into Kalkars, a brutish,

mongrel breed of lunar invaders. President Petrov became Jarth, Jemadar

of the United Teivos of America. Commander Bergst of Chicago ’s Red Guard

was transformed into Brother-General Or-tis, the new Commandant of Chicago.

And James Julian, the story’s tragic lead character, morphed into Julian

the Ninth, one in a long line of Julian family heroes. Burroughs re-titled

the story “The Moon Men” and cleverly made it a sequel to an as-yet-unwritten

story.

Within months, Burroughs

penned “The Moon Maid,” the first third of what was becoming a multi-generational

narrative. This segment takes place 100 years before “The Moon Men.” It’s

the story of Julian the Fifth, whose unfortunate spaceship crashes on the

Moon. His subsequent adventures in a world beneath the lunar surface launch

a chain of events leading to the Kalkar invasion of Earth.

“The Moon Maid” quickly sold

to Argosy All-Story Weekly, which serialized it in spring of 1923.

All-Story had no choice now but to publish its “sequel,” the rewritten

“Under the Red Flag,” in February and March 1925.

Finally, there remained for

Burroughs the task of satisfactorily concluding the Julian family saga.

Six months after publishing “The Moon Men,” All-Story Weekly serialized

his “The Red Hawk,” the final piece of the chronicle. Jumping 300 years

beyond “The Moon Men,” it describes Julian the Twentieth’s role in the

revolt that ends Kalkar tyranny on Earth. All three stories were collected

in book form as the novel The Moon Maid in 1926.

The Moon Maid (the

title refers to a princess in the first novella and has nothing to do with

most of the book) is strikingly different from most of the Burroughs canon.

Sure, it features plenty of the author’s traditional scenes of romance,

capture, and daring escape, particularly in the first section. But this

novel is consistently dark; victory is never certain and violent death

lurks everywhere. Anyone familiar with the indestructible Tarzan and John

Carter, who always survive insurmountable odds with seldom a scratch, will

be startled by

The Moon Maid. Julian the Fifth, for instance, returns

to Earth successfully at the end of the first novella, but he sacrifices

his life in a horrible explosion during the prologue to Part II. Julian

the Ninth is beheaded by a Kalkar executioner at the close of “The Moon

Men.” And Moses Samuels, another heroic and likeable figure in that same

section, is gruesomely tortured and murdered by his oppressors in an especially

heartbreaking scene.

The Moon Maid also

differs from more typical Burroughs fare in the razor-sharp social and

political commentary that literally saturates it.

Burroughs begins to skewer

state socialism early on in the book. In one scene, a fellow prisoner describes

to Julian the Fifth the collapse of a once great lunar civilization:

“Ages

ago we were one race, a prosperous people living at peace with all the

world . . . . There were ten great divisions, each ruled by its Jemadar,

and each division vied with all the others in the service which it rendered

to its people. There were those who held high positions and those who held

low; there were those who were rich and those who were poor, but the favors

of the state were distributed equally among them, and the children of the

poor had the same opportunities for education as the children of the rich,

and there it was that our troubles first started.”

A secret society called The

Thinkers, the prisoner explains, filled the people of Va-nah, the Moon’s

interior world, with envy and dissatisfaction. They eventually overthrew

the Jemadars and drove the ruling class from power. But . . .

“The

Thinkers would not work, and the result was that both government and commerce

fell into rapid decay. They not only had neither the training nor the intelligence

to develop new things, but they could not carry out the old that had been

developed for them. The arts and sciences languished and died with the

commerce and government, and Va-nah fell back into barbarism.”

The Kalkars, who invade Earth

with the help of a traitorous Earthling in Part II, are descendants of

The Thinkers. And naturally, they transplant their failed political and

social systems to Occupied Earth.

In the second novella, we’re

told that “the accursed income tax” in agrarian, collectivized America

is one percent of all a family buys or sells during a month, paid at the

end of each month with produce or manufactured goods. But since nothing

has any fixed value, the tax collectors’ appraisals are based on the highest

market values for the month. Says a Kalkar tax collector to Julian the

Eighth:

“You

paid five goats for half your weight in beans, and as everyone knows that

beans are worth twenty times as much as coal, the coal you bought must

be worth one hundred goats by now, and as beans are worth twenty times

as much as coal and you have twice as much beans as coal your beans are

now worth two hundred goats, which makes your trades for this month amount

to three hundred goats. Bring me, therefore, three of your best goats.”

I’d love to hear the late

Murray Rothbard dissect that nonsense.

Edgar Rice Burroughs was

no libertarian. His “Americans,” as the subjugated Earth people are called

in the book, worship a tattered American flag (called simply The Flag)

and sing “Onward Christian Soldiers” during forbidden (and oddly secular)

religious services. And despite all their talk of freedom and independence,

I suspect these Americans would ultimately replace their Kalkar masters

with equally despotic rulers. But Burroughs’ contemptuous portrayal of

Earth just prior to its alien invasion — a planet so dedicated to “peace

at any price” that possession of firearms is illegal worldwide and “even

edged weapons with blades over six inches long [are] barred by law” — shows

that his heart was largely in the right place. Burroughs was a lover of

freedom. And no libertarian should find argument with the old American

virtues of self-reliance, physical courage, and survival so explicitly

depicted in The Moon Maid.

I think The Moon Maid

is a surprisingly overlooked Edgar Rice Burroughs masterpiece. Its epic,

generations-long “future history” was unique for its time. It’s a brilliant

early example of social extrapolation in science fiction. And it delivers

an exciting and inspiring story that should delight most liberty-seekers.

(I highly recommend the 2002

“complete and restored” University of Nebraska Press edition of The

Moon Maid. It restores all the passages deleted from both the magazine

and book versions over the last eight decades.).

May 23, 2005

Wally

Conger is a marketing consultant and writer living on California ’s

central coast. He has been a non-political, anti-party activist in the

libertarian movement since 1970. His blog of unfinished essays and spontaneous

eruptions can be found at wconger.blogspot.com.

Wally

Conger Archive at www.Strike-the-Root.com

discuss

this column in the forum

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()