WHAT WE KNOW

OF PLANET MARS

Professor Edward S. Holden

Draws Line Between Facts

and Fancies

THINGS SEEN ON MARS

No Direct Evidence of Human

Life -- Little Water or Air

TESLA'S IDEAS CRITICISED

By Edward S. Holden

(Copyright, 1901, by the S. S. McClure company.

Reprinted by special permission of McClure's Magazine)

Astronomy

has done so many wonderful things in t he past, and is accomplishing such

marvels in the present, that it is sometimes difficult to realize its limitations.

If, by merely examining the spectrum of a star, astronomers can determine

the velocity with which the earth, and the whole solar system, is now approaching

that star, why should it be so difficult to say whether it is, or is not,

likely that the planets are fitted to sustain human life? If the spectroscope

can do so much, how is it that our greatest telescopes can do so little

towards settling a question that seems to be comparatively simple? At first

sight, the problem appears to be a mere matter of observation, and the

solution to be close at hand and obvious.

Astronomy

has done so many wonderful things in t he past, and is accomplishing such

marvels in the present, that it is sometimes difficult to realize its limitations.

If, by merely examining the spectrum of a star, astronomers can determine

the velocity with which the earth, and the whole solar system, is now approaching

that star, why should it be so difficult to say whether it is, or is not,

likely that the planets are fitted to sustain human life? If the spectroscope

can do so much, how is it that our greatest telescopes can do so little

towards settling a question that seems to be comparatively simple? At first

sight, the problem appears to be a mere matter of observation, and the

solution to be close at hand and obvious.

Let us see what the obstacles really are. When the planet

Mars is nearest to the earth its distance is never less than 35,000,000

miles. Usually it is much greater. The moon's distance is about 240,000,

so that Mars is always 146 times more distant than the moon. It is seldom

possible to use a magnifying power of more than 600 diameters to examine

Mars, under such conditions, no better than the moon can be seen in a filed

glass magnifying about four times. If any one will examine the moon with

a common opera-glass he will appreciate the difficulty of making out an

answer so far-reaching a question by mere gazing.

NO DIRECT EVIDENCE OF HUMAN LIFE

Under ordinary circumstances a square patch on the planet

wit sides of twenty miles would go entirely unnoticed. The best telescopes

can never show us markings of the size of most of the great cities on the

earth. Direct evidence of human life is not to be expected. All such evidence

must be indirect. We must ask what is the climate of Mars. If it is much

colder than the arctic regions (as it is), human life (that is, of the

kind we know about) cannot exist there. Is there an atmosphere about the

planet with sufficient air, and air of the right kind, to sustain human

life? Is there water? It is upon the answers to question s of this kind

that our final judgment must depend. The fundamental problem reduces itself

to an inquiry whether the planet is inhabitable -- whether it presents

the conditions of habitability - and not whether it is actually inhabited

by human beings.

There are many other kinds of life besides human life.

If there were no land at all on the earth -- if it were all a single ocean

-- there might e a vigorous population of fishes. Or, if there were not

enough air surrounding it for men to breathe, still there might e animals

which could exist and multiply. Or, if the terrestrial temperatures were

too high for human beings, it might be perfectly suitable for reptiles.

Or, again, if all conditions were unfavorable for animals, a vigorous plant

life might still exist.

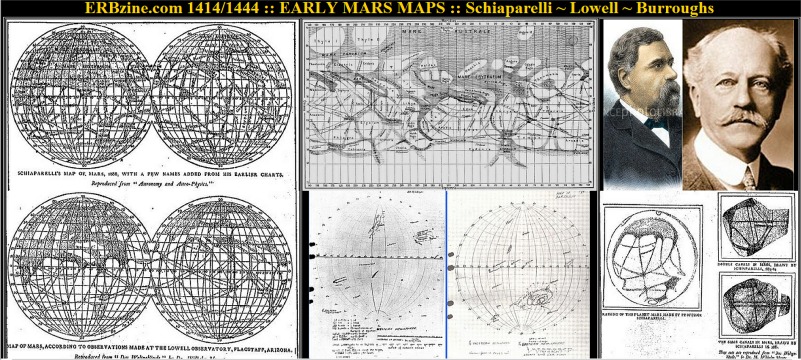

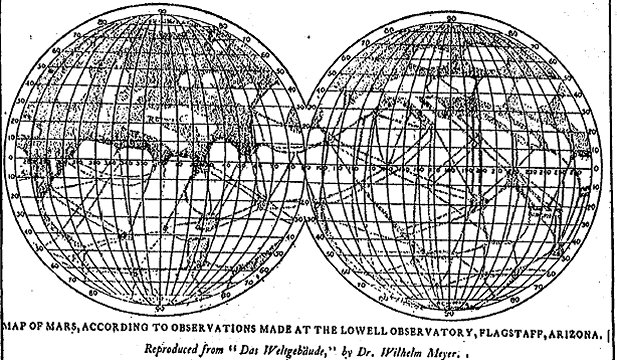

THINGS SEEN ON MARS MULTITUDINOUS

A complete account of the appearances observed on the

planet Mars would fill volumes. During a single opposition many hundreds

of drawings and sketches are secured, to say nothing of measures, etc.

The illustrations presented here will serve to show the kind of evidence

afforded by good drawings made at the telescope. No thorough-going discussion

of the material available has yet been printed. Mr. Percival Lowell has

published a volume dealing with his recent work at Flagstaff, in Arizona,

and M. Camille Flammarion has issued useful book on Mars; but many valuable

series are yet unpublished.

The instant we imagine human life anywhere -- on the earth

or on a distant planet -- the place where this life may be takes on an

entirely new relation to us. Love can be there, and joy and sorrow, and

we realize that we have a deep and new interest in any and every spot where

such human life is possible. One of the first and most natural questions

asked about the moon, or about a distant planet, is, and always will be,

"Is it inhabited?" or, "Is it fitted to be the abode of men?" If the answer

is "No," a lively scientific curiosity may remain, but the nature

of this curiosity is completely changed. There is no lack of such inquisitiveness

in regard to the moon, for example, and yet the general public has long

ago accepted the fact that the moon is to be studied like a specimen

in a museum; that it has no life now, and that, in all probability, it

never had any.

WHY PEOPLE ARE INTERESTED IN MARS.

The case is not the same for Mars. For one reason and

another the general reader has come tot he conclusion that human life may

exist, and probably does exist, on this planet as well as on our own earth.

Hence the extraordinary attention that has been paid to quite extravagant

and baseless publications regarding it.

Let us turn to the moon for a moment and see what is the

basis of the general belief that the moon is not fit to sustain life. In

the first place, geologists tell us that the surface of the moon is simply

a cooled lava bed. Astronomers have looked at every spot on the part of

the moon presented to us thousands of times, without once detecting any

signs of the existence of living beings. It is a certainty that no

human life now exists there, because the lunar temperature is so low that

no such life could withstand it. There is no water and no air; certainly

not enough air to sustain human life, if there is no water there can be

no life. For thousands of years there has been no considerable action of

water on the lunar mountain chains, and for thousands of years there has

been no human life there. In all likelihood there never has been any.

Our interest in the moon is then, a scientific interest

only. We have no feeling of brotherhood as to the satellite of the earth.

It is intensely interesting as an object of study and in its way. But this

way is devoid of all human interest. In Kepler's time it was reputed

to be peopled, and excited a different feeling.

Mars in now thought of by the general reading public somewhat

as the moon was in the days of Kepler. Its "continents," "stars," "lakes,"

"oases," "canals," its "intelligent inhabitants," its engineers," etc.,

have been so often referred to in popular writings that they have been

more or less generally accepted, except by those whose business it is to

study the planet telescopically. It is safe to say that only a few professional

astronomers accept these things without reserves. It is worth while to

recite how this popular acceptance of doubtful matters came about.

WHAT EARLIEST OBSERVERS RECORDED

The earliest observers of the planet Mars( in the seventeenth

and eighteenth centuries) recorded markings on its surface that were permanent

in position, just as the seas and oceans of the earth are permanent. A

large part of the surface of the planet was reddish, and the general opinion

came to be that the red areas were land. There was absolutely no scientific

reason whatever for this belief. This opinion was widespread for

this belief. This episode was widespread before the time of Sir John Herschel,

but the publication of his famous "Outlines of Astronomy" -- the first

elementary exposition of the science -- fixed it in the popular mind.

If the red areas were "land," then the dark markings were

"water," the larger ones "seas," the lesser "lakes," and son on. The dark

regions on Mars were often bluish in color. For that reason, and for that

reason alone, they were called "oceans." The mischief began with its nomenclature.

It assumed as true that which was utterly without proof. The observing

astronomers knew, and always have known, just how little positive proof

was forthcoming; but some nomenclature was necessary, and the words "lakes,"

"canals," etc. were convenient, provided they were not misunderstood. And

they certainly have been misunderstood. From this mistaken nomenclature

a host of beliefs has arisen.

HOW POPULAR THEORIES HAVE GROWN

When Professor Roentgen discovered the action of his

wonderful "rays," he was in doubt about their nature. In a truly scientific

fashion he named them "X-rays"; that is to say, "rays whose nature we do

not yet comprehend." He committed himself to no hypothesis. Not only were

scientific men left free to choose a suitable explanation and an appropriate

name at leisure, but the popular intelligence was informed, by their designation,

that scientific certainty had not yet been attained. If the astronomers

of Herschel's day had had called the red areas of Mars Y and the dark ones

Z many errors would have been avoided.

It is curious to remark how one error has led to another

and another in a regular implication. For example, the large dark areas

on Mars were called "seas," the smaller ones "lakes." Narrow streaks connecting

"lakes" with "seas" would naturally have been called "rivers." But rivers

on the earth are sinuous; and now winding, meandering, narrow streaks have

yet been discovered on Mars. Hence, as the narrow dark streaks on t he

planet were straight they were called "canals." A "canal" implies

"commerce" and "intelligent engineers" and so forth. AGain, it has been

maintained (why I do not know) that rivers on Mars were straight because

the land was flat. On the earth rivers in flat countries are far from straight.

So it became a commonplace that the surface of Mars was quite flat, until

the observers at Mount Hamilton discovered mountain chains on its surface.

SOME FACTS ABOUT THE "CANALS"

The dark, narrow, straight "canals" were at first only

seen in the "continents." But by and by the same observers discovered "canals"

in the midst of the "seas." A "canal" in the midst of a "sea" is an anomaly,

but the name still constrained opinion. One would think that the idea could

not long persist.

These "canals" are never less than twenty miles wide.

To dig the network of "canals" shown on Schiaparelli's chart would require,

it has been calculated, the labor of every man, woman, and child of a population

as dense as that of Belgium; and their labor would have to be extended

over centuries. At times these "canals" are (apparently) filled up and

vanish. In a region where one "canal" formerly existed two new ones appear,

hundreds of miles in length. This "process" of the creation of extended

"double canals" may last only a few hours. Changes of this sort have been

referred to "irrigation" experiments on the planet. The latest book on

the subject assumes the planet to need an extensive system of irrigation

ditches. The south polar snows melt, it is there said, and irrigate the

southern hemisphere and much of the northern. The northern polar snows

melt and irrigate the northern hemisphere and much of the southern.

"The corresponding problem on the earth would be to irrigate

San Francisco, Chicago, New York, Rome, and Tokio from the snow melting

at the south pole, and to irrigate Valparaiso, the Cape of Good hope, and

Australia from the snow melting at the north pole; all the irrigated land

lying between New York, etc. on the north and the Cape of Good Hope, etc.,

on the south, to be irrigated alike (through the same canals) from the

north and south poles."

It is not necessary to pursue these fanciful expositions

any further. They all flow from the mistaken nomenclature of "land" and

"water" adopted long ago and followed with persistency. Sir William Herschel's

dictum of 1783 that "the analogy between Mars and the earth is perhaps

by far the greatest in the solar system" evidently needs closer examination.

LITTLE OR NO WATER ON MARS

The point upon which he founded his confusion was, at

the time (1783), well taken. He observed that the poles of Mars were sometimes

covered with polar caps of a white material that he assumed to be snow.

The "snow" was greatest in amount when the poles were coldest, just as

happens on the earth. As the amount of solar heat increased the "snow caps"

grew smaller and gradually disappeared. He supposed them to melt and to

become water. The explanation was correct, so far as his knowledge then

went. We now know two facts that make it impossible. In the first place,

according to the best knowledge attainable, the temperature of Mars is

always far below the freezing point. Water can never melt on Mars. In the

second place, there is, in fact little or no water on Mars. The observations

at the Lick Observatory have shown this conclusively, and this result is

now generally accepted.

The "polar caps" exist, however. What are they? The answer

is that it is not (yet) certainly known. They are X for the present, like

Professor Roentgen's rays. It is likely that they may be composed of carbon

dioxid. This vaporizes (and becomes invisible at -100o

of Fahrenheit's thermometer. At a lower temperature than this it

is deposited as a white "snow." A layer an inch thick (or less) would account

for all the observed phenomena. This explanation may not be correct, but

it is worthy of serious examination. Whether it is correct or not, it is

certain that the polar caps of Mars are not composed of "snow."

Snow is water, and there is no water to speak of on the

planet. Moreover, the polar caps "melt," and the temperature of the arctic

regions of Mars is always below the melting temperature of water. The polar

caps of Mars are not "snow": they may be carbon dioxid; they certainly

are composed of some substance that acts much as carbon dioxid would act

if it were exposed to such conditions as exist at the poles of Mars - let

us call it X for the present, after the safe and scientific fashion of

Professor Roentgen.

AIR AND CLOUDS ALSO SCARCE

Not only is there no water on Mars, but there is no air

or little. Spectroscopic observations at the Lick Observatory, far more

complete and thorough-going than those made at other stations, lead to

the conclusion that the atmosphere on Mars is certainly lower in amount

than that surrounding the summits of the highest Himalayan peaks. It is

probably much less than this; at any rate, there is not sufficient air

to sustain human life. It is by no means certain that what air there is,

is the right kind for human beings to breathe. All telescopic observation

leads to the conclusion that there are no clouds on Mars. If there were

air and water, clouds would certainly form. In thousands of observations

clouds have not been seen. The sky of Mars is absolutely sunny. Clouds

have only been suspected on two or three occasions. It is safe to say that,

speaking generally , Mars is a planet without water, without air in any

marked quantity and totally unfit for the abode of human beings. Its nearest

analogue in the solar system is our own moon, as was pointed out years

ago by George Bond, the director of the Harvard College Observatory.

The same conclusion was also reached early in the history

of the observations of Mars made at the Lick Observatory, and the latter

observations made there have reinforced it with new proofs. Several observers,

notably M. Flammarion in France, and Mr. Lowell in America have taken a

different view, which has been widely spread through their scientific and

through their popular writings. The daily press of the United States and

elsewhere has found "Human Life on Mars" to be a taking headline, and it

has been often employed . The general reader, hearing only one side, and

having the unfortunate nomenclature of "seas" and "canals" before his eyes,

has naturally, accepted results that appealed to his imagination and that

he had no way of testing for himself.

POPULAR OPINIONS MUST CHANGE

In the light of what has gone before, it is clear that

a change of popular opinion must be made. Popular opinion has no other

desire than to be well founded, and is entirely ready to be guided by the

judgment of experts. We may appeal to them. Professor Young of Princeton

has this to say on the matter of temperature on Mars: "Recalling the fact

that the the solar radiation is less than half as intense as here, the

inference is almost irresistible that the temperature must be appallingly

low - so low that water, if it exists at all, can exist only in the form

of ice." Professor Newcomb of Washington remarks in a recent paper: "Mars

has little or no atmosphere. There are few or no clouds on Mars." It is

by no means certain, he says, that the polar ice caps are ice at all. Other

judgments of the same sort from astronomers of equal authority could be

quoted. These will suffice.

A confirmation of the views held by the leading American

astronomers has lately come from an unexpected source. The planet Mars

has been assiduously studied in recent years in the observatory of M. Flammarion,

near Paris, by his colleague, M. Antionadi. There, as elsewhere, the "canals"

on the planet have been seen, usually as long, narrow, dark lines lying

on the arcs of great circles of the surface. The experiments of M. Daubree

have shown that if a planet is composed of an exterior layer of crust over

an interior nucleus that is shrinking a series of rogations, like mountain

chains, will be produced. If, on the other hand, the nucleus is expanding,

a series of long cracks, crevasses, and canons will result. The "canals"

on Mars are probably merely long crevasses in its outer crust, produced

in this way.

ANTIONADI ON "DOUBLE CANAL"

The "doubling" of the Martian canals has been studied

by M. Antionadi also. He describes the phenomenon graphically. If, he says,

the Seine would suddenly disappear, and if two new rivers who'll be created,

one running form Nanies to Marseilles, the other from Dunkirk to Strassburg,

we should have a precise terrestrial analogue to the appearance of a "double

canal" in Mars. (What a problem in "engineering" this would be!) To arrive

at an explanation of such appearances, Mr. Antionadi has made a careful

study of the optical illusions that attend prolonged and strained vision

of delicate markings of this nature, and he has come unreservedly to the

conclusion that the doubling of the canals on Mars arises from defective

focussing of some kind, either of the telescope or of the observer's eye

(through fatigue).

One of his experiments may be tried by any one who will

take the trouble to rule a fine line on a visiting card and to look at

it from a distance through an opera glass. A slight disturbance of the

focal adjustment of the glass or a slight fatigue of the eye will always

produce a double image of the single line. These experiments throw a flood

of light on the appearances observed on Mars. They explain why the double

canals are only to be seen after prolonged and strained vision, why they

are more often seen in short than in long telescopes, etc.

PHYSICAL LAWS WILL EXPLAIN MUCH

The experiments of M. Antionadi seem to prove that the

doubling of the canals on Mars is always the result of an optical illusion.

His conclusions are noteworthy in themselves, and also as a sign of a return

to rationality in the explanation of the physical appearances presented

by the surface of Mars These are to be explained by physical laws, and

not by intervention of "human beings like ourselves," "engineers" engaged

in "irrigation works," or in "commerce," and possessed of a burning desire

to communicate with their brothers on the earth by signal lights. The apparatus

of the sensational astronomical journalist is made useless in an instant.

It is interesting to note that these experiments were conducted by an assistant

to M. Flammarion, who has long been the high priest (in France) of the

doctrine of human life on Mars.

In the foregoing no attempt has been made to discuss technical

points. These are matters for the scientific journals and for professional

astronomers. What is here set down is so simple and obvious that no special

knowledge is required to interpret it. It is plain to all that we have

the right to conclude that there is not the slightest reason to believe

that human life can exist on the planet Mars.

MAN WOULD FREEZE ON MARS

If by some miracle a man were suddenly transported to

that planet he would undoubtedly freeze solid in an exceedingly short time.

He would find no water there, nor sufficient air to breathe. It is more

than likely that what air there may be is of a kind fatal to human life.

So far as we know, there is no likelihood that life exists on any other

planet than earth. There is not a scintilla of evidence to show that Mercury,

Venus, Jupiter, Saturn, and the rest are better fitted to sustain human

life than Mars.

These are not the conclusions that have been generally

accepted by the readers of recent popular astronomical literature. But

any one who will take the pains to examine all the evidence can come to

no other judgment.

TESLA'S THEORY CRITICISED

(Since the foregoing article was written Mr. Nikola Tesla

has announced that he is "almost confident" that certain disturbances of

his apparatus arise from electric signals received from some source beyond

the earth. They do not come from the sun, he says hence, they must be of

planetary origin, he thinks, probably from Mars. It is a rule of sound

philosophizing to examine all probable causes for an unexplained phenomenon

before invoking improbable ones. Every experimenter will say that it is

"almost" certain that Mr. Tesla has made an error and that the disturbances

in question come from currents in our air or in the earth. How can any

one possibly know that unexplained currents do not come from the sun? The

physics of the sun is all but unknown as yet. At any rate, why call the

currents "planetary" if one is not quite certain?

Why fasten the disturbances of Mr. Tesla's instruments

on Mars? Are there no comets that will serve the purpose? May not the instruments

have been disturbed by the Great Bear -- or the Milky Way -- or the Zodiacal

light? There is always a possibility that great discoveries in Mars and

elsewhere are at hand. The triumphs of the science of the past century

are a striking proof. But there is always a strong probability that new

phenomena are inexplicable by old laws. Until Mr. Tesla has shown his apparatus

to other experimenters and convinced them as well as himself it may safely

be taken for granted that his signals do not come from Mars.

Astronomy

has done so many wonderful things in t he past, and is accomplishing such

marvels in the present, that it is sometimes difficult to realize its limitations.

If, by merely examining the spectrum of a star, astronomers can determine

the velocity with which the earth, and the whole solar system, is now approaching

that star, why should it be so difficult to say whether it is, or is not,

likely that the planets are fitted to sustain human life? If the spectroscope

can do so much, how is it that our greatest telescopes can do so little

towards settling a question that seems to be comparatively simple? At first

sight, the problem appears to be a mere matter of observation, and the

solution to be close at hand and obvious.

Astronomy

has done so many wonderful things in t he past, and is accomplishing such

marvels in the present, that it is sometimes difficult to realize its limitations.

If, by merely examining the spectrum of a star, astronomers can determine

the velocity with which the earth, and the whole solar system, is now approaching

that star, why should it be so difficult to say whether it is, or is not,

likely that the planets are fitted to sustain human life? If the spectroscope

can do so much, how is it that our greatest telescopes can do so little

towards settling a question that seems to be comparatively simple? At first

sight, the problem appears to be a mere matter of observation, and the

solution to be close at hand and obvious.