| passed away. It avoids a lot of unpleasantness.

To a solicitor, the commands of a client are ironclad. And so, right

after the Earl of Streatham had died, a formal notice appeared among the

day's legal advertisements, advising all interested parties that the papers

of the Mildin family would be unsealed.

The ad attracted the scant attention that usually follows any legal

notice. For at the appointed hour there were present in the offices --

Mr. Edmund Bennet, the solicitor who handled the case, and two clerks of

his office. No one else showed up.

The boxes and chests containing the memorabilia lay on a broad table.

At precisely 11 AM, Mr. Bennet picked up the certified copy of the will,

read the applicable paragraph, asked formally if there were any objections

to carrying out the proviso. Naturally, since no outsider was present,

there were none. Forthwith, the seals were broken and the boxes opened.

Most of the material was typical of that collected by old English families.

There were account books and records dating back to the time of Henry the

VIIIth. Stacked neatly in their containers were yellowing, crumbling letters

from kings, queens, dukes and earls.

"The old boy had some very distant relatives," one of the partners shrugged.

"We might as well ask them if they want this stuff -- if not, we'll just

turn it all over to some museum. There's really nothing startling here.

. ."

The office staff began packing all the papers back into the boxes when

one of the clerks, who had b been rummaging through a brassbound chest,

let out a sudden whoop of amazement.

"Good Lord!" the clerk exclaimed. "Look at this!"

He thrust forward a thick packet of papers that looked as though they

made up a manuscript of some sort. Hand-printed neatly on the cover page

was the following:

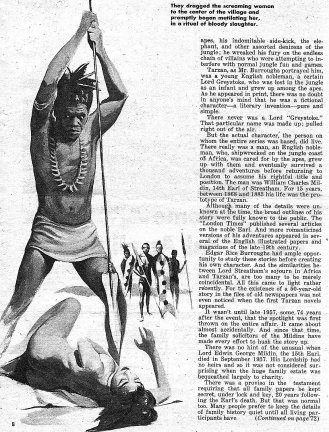

"An account of the incredible adventures of Lord William Charles Mildin,

the 14th Earl of Streatham, who lived for nearly 15 years among the apes

and animals of the African jungle.

Astounded, the law clerks took the manuscript and began reading through

it. They were still at the job more than three hours later -- for the manuscript

consisted of more than 1,500 pages of fine, tiny-charactered handwriting.

"By God!" Henry Randolph, the senior partner of the firm, muttered.

"I remember now -- there was some story about Lord Edwin's father.

I heard something strange and weird -- years ago -- when I was only a child.

. ."

The story that then unfolded was odder than odd -- stranger than strange

-- and proved once again that truth can often put fiction to shame.

"I was only eleven," wrote Lord Mildin, the father of the Earl of Streatham

who died in 1937, "when, in a boyish fit of anger and pique, I ran away

from home and obtained a berth as cabin boy aboard the four-masted sailing

vessel, Antilla, bound for African ports-of-call and the Cape of

Good Hope. . ."

Lord William described the voyage from England and down the African

Coast in great and meticulous detail. Then, he told of a violent storm

which caught the Antilla in the Gulf of Guinea -- a storm which,

raging for over 72 hours, wrecked the vessel.

"When the wind subsided, I dis- |