Science

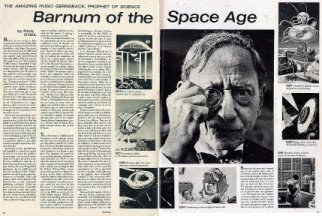

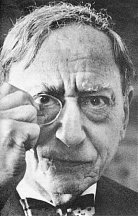

is now so big, so flamboyant and so barnacled with politicians, press agents,

generals and industrialists that Hugo Gernsback, who invented it back in

1908 (and has re-invented it, annually, since) can scarcely make himself

heard above the babble of the late-comers. Although he is now 78, Gernsback

is still a man of remarkable energy who raps out forecasts of future scientific

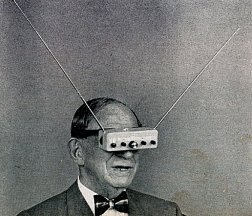

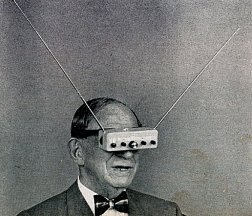

wonders with the rapidity of a disintegrator gun. He believes that millions

will eventually wear television eyeglasses--and has begun work on a model

to speed the day. "Instant newspapers" will be printed in U.S. homes by

electromagnetic waves, in his opinion, as soon as U.S. publishers wrench

themselves out of the pit of stagnant thinking in which Gernsback feels

they are wallowing at present. He also believes in the inevitability of

teleportation--i.e., reproducing a ham sandwich at a distance by electronic

means, much as images are now reproduced on a television screen.

Science

is now so big, so flamboyant and so barnacled with politicians, press agents,

generals and industrialists that Hugo Gernsback, who invented it back in

1908 (and has re-invented it, annually, since) can scarcely make himself

heard above the babble of the late-comers. Although he is now 78, Gernsback

is still a man of remarkable energy who raps out forecasts of future scientific

wonders with the rapidity of a disintegrator gun. He believes that millions

will eventually wear television eyeglasses--and has begun work on a model

to speed the day. "Instant newspapers" will be printed in U.S. homes by

electromagnetic waves, in his opinion, as soon as U.S. publishers wrench

themselves out of the pit of stagnant thinking in which Gernsback feels

they are wallowing at present. He also believes in the inevitability of

teleportation--i.e., reproducing a ham sandwich at a distance by electronic

means, much as images are now reproduced on a television screen.

Gernsback pays absolutely

no attention, while issuing such pronunciamentos, to the fact that the

public is rapidly becoming inured to scientific advance and that scientists

themselves may not actually stand in need of his advice and counsel. He

paid as little attention to the head-tapping some of his announcements

set of in the 1920s--a period in which he was often considered nuttier

than Albert Einstein himself.

Gernsback,

in fact, has felt himself impelled to preach the gospel of science ever

since his youth in Luxembourg--not so much, apparently, for the good of

science as for his own satisfaction and the delights of seeing his name

in the papers. In 55 years as a self-appointed missionary, he has stiffly

ignored both the cackling of the heathen and the cries of competing apostles.

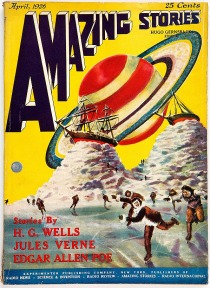

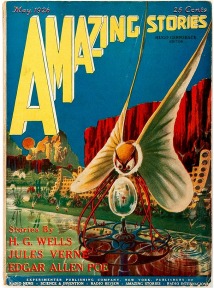

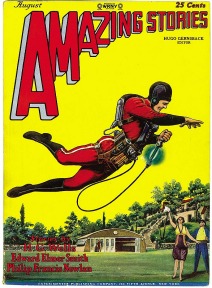

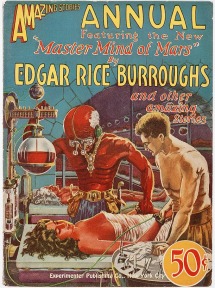

Moreover, as founder, owner, and guiding spirit of Gernsback Publications,

Inc., a New York-based publishing enterprise which has produced a succession

of scientific and technical books and magazines (among themAmazing Stories,

the first science-fiction monthly), he has not only provided himself with

a method of firing endless barrages of opinion, criticism and augury but

the means of making a good deal of money as well.

Gernsback,

in fact, has felt himself impelled to preach the gospel of science ever

since his youth in Luxembourg--not so much, apparently, for the good of

science as for his own satisfaction and the delights of seeing his name

in the papers. In 55 years as a self-appointed missionary, he has stiffly

ignored both the cackling of the heathen and the cries of competing apostles.

Moreover, as founder, owner, and guiding spirit of Gernsback Publications,

Inc., a New York-based publishing enterprise which has produced a succession

of scientific and technical books and magazines (among themAmazing Stories,

the first science-fiction monthly), he has not only provided himself with

a method of firing endless barrages of opinion, criticism and augury but

the means of making a good deal of money as well.

Neither Gernsback's instinct

for the unorthodox, however, nor his unabashed sense of theater has prevented

his full acceptance as a member of the science community. Dozens of today's

top scientists were attracted to their calling by reading his magazines

as boys, and a good many--including Dr. Donald H. Menzel, director of the

Harvard Observatory-- earned money for college tuition by writing for them.

He is heralded as the "Father" of modern science fiction (the statuettes

which are annually awarded to its top writers are, in his honor, known

as Hugos, but he is simultaneously a member of the American Physical Society

and a lecturer before similar learned groups. The greatest inventors and

scientists of the early 20th Century--among them Marconi, Edison, Tesla,

Goddard, DeForest and Oberth--corresponded freely with him and came, in

many cases, to admire and confide in him as well. The Space Age caused

no diminution of this cozy relationship with the great; RCA's General David

Sarnoff is among his friends and pen pals, and so are former Atomic Energy

Commissioner Lewis L. Strauss and President Kennedy's science adviser,

Dr. Jerome Wiesner.

This

admiration is solidly based. Gernsback, in his unique career, has not only

done his best to prepare the public mind for the "wonders" of science but

has sometimes managed to tell science itself just what wonders it was about

to produce. for instance, he conceived the essential principles of radar

aircraft detection in 1911--a year when the airplane itself was barely

able to stagger off the ground. This early concept was so complete that

Sir Robert Watson-Watt, whose radar tracking devices helped save London

in the Battle of Britain, considers him the original inventor.

This

admiration is solidly based. Gernsback, in his unique career, has not only

done his best to prepare the public mind for the "wonders" of science but

has sometimes managed to tell science itself just what wonders it was about

to produce. for instance, he conceived the essential principles of radar

aircraft detection in 1911--a year when the airplane itself was barely

able to stagger off the ground. This early concept was so complete that

Sir Robert Watson-Watt, whose radar tracking devices helped save London

in the Battle of Britain, considers him the original inventor.

Gernsback not only coined

the word "television" (he refuses to accept credit for that since he has

discovered a Frenchman used an equivalent of the word a little earlier)

but in 1928, as owner of New York's radio Station WRNY, actually instituted

daily telecasts with crude equipment. His list of successful scientific

prophecies is almost endless and the persicacity with which he has reported

scientific thinking on the part of others is remarkable. In the 1920s,

to make the point, he was force-feeding his readers all sorts of crazy

stuff about atomic energy and about the problems of weightlessness and

orbital rendezvous to be encountered in "space flying."

It

is, therefore, difficult not to believe that U.S. science has been influenced

in many ways as a result of Gernsback's extraordinary career in evangelism;

certainly it has absorbed a flavor, unobtainable by any other means, simply

through harboring him in its midst, like a peppercorn in a pudding, for

a full half-century. The effect, however, would hardly have been achieved

were it not for a certain duality in Gernsback's nature. While he is cuckoo

for science and takes a Barnum like joy in the bizarre (he is so proud

of having invented a device for hearing through the teeth that he has listed

it in Who's Who), he is also a man of real intellect in whose mind are

mated astonishing scientific intuition, an instinct for command and a shrewd

if exotic sense of business.

It

is, therefore, difficult not to believe that U.S. science has been influenced

in many ways as a result of Gernsback's extraordinary career in evangelism;

certainly it has absorbed a flavor, unobtainable by any other means, simply

through harboring him in its midst, like a peppercorn in a pudding, for

a full half-century. The effect, however, would hardly have been achieved

were it not for a certain duality in Gernsback's nature. While he is cuckoo

for science and takes a Barnum like joy in the bizarre (he is so proud

of having invented a device for hearing through the teeth that he has listed

it in Who's Who), he is also a man of real intellect in whose mind are

mated astonishing scientific intuition, an instinct for command and a shrewd

if exotic sense of business.

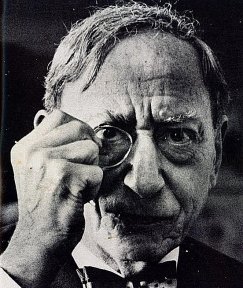

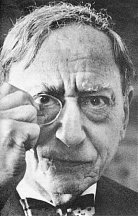

People who are only hazily

aware of his background and accomplishments often expect to find him at

a desk in a loft and dressed up like Thomas Alva Edison. They are almost

uniformly taken aback when they meet him in person. Gernsback is a dude

of the first order. He owns a vast collection of shirts and ties from Sulka

and Charvet, uses a toilet water of splendid fragrance and wears suits

reminiscent at once at Rome and Bond Street. He is an art collector, a

world traveler and a connoisseur of champagnes. He not only speaks German,

French, English and the patios of Luxembourg with equal facility, but he

does so in tones of ducal authority. He is at his most impressive in restaurants.

He screws a monocle into one eye while inspecting menus and rejects wine

which does not live up to his expectations as well as any food served on

a plate which has not, in his opinion, been sufficiently warmed. If the

subsequent offering does not please him, he sends that back too. Gernsback's

record of consecutive, one-sitting refusals now stands at three, for both

food and wine.

A DEEP CONCERN FOR SEX

AND FUNERALS

He

is perfectly capable of humor--he has, in fact, a genuine sense of comedy--but

he habitually wears that grave and forbidding manner which was the hallmark

of big-power diplomats before World War I. His effect on a listener who

is only gradually becoming aware of his dearer interest can be fascinating.

Gernsback devotes a good deal of thought toward sex (he publishes, among

other works, a magazine entitled Sexology, which aims to present a scientific

view of problems inherent in the reproductive processes). He also broods

about funerals; he is against them, feels the world is gradually being

converted into one huge graveyard, and had a plan for freezing corpses

and firing them into space at speeds calculated to remove them, once and

for all, from our planetary system. Gernsback delivers such monologues

with epic gravity and assurance--with exactly the air, one cannot suspect,

which Bismarck wore in directing the Congress of Berlin.

He

is perfectly capable of humor--he has, in fact, a genuine sense of comedy--but

he habitually wears that grave and forbidding manner which was the hallmark

of big-power diplomats before World War I. His effect on a listener who

is only gradually becoming aware of his dearer interest can be fascinating.

Gernsback devotes a good deal of thought toward sex (he publishes, among

other works, a magazine entitled Sexology, which aims to present a scientific

view of problems inherent in the reproductive processes). He also broods

about funerals; he is against them, feels the world is gradually being

converted into one huge graveyard, and had a plan for freezing corpses

and firing them into space at speeds calculated to remove them, once and

for all, from our planetary system. Gernsback delivers such monologues

with epic gravity and assurance--with exactly the air, one cannot suspect,

which Bismarck wore in directing the Congress of Berlin.

Gernsback is a firm believer

in the effects of environment and conditioning and feels that both his

personality and his career were firmly shaped in early childhood. He was

as bald as an egg until he was five years old and his father, a wealthy

wholesaler of wines, hustled him all over Europe diligently seeking a cure

for this peculiarity. Gernsback eventually sprouted hair on his own, apparently

out of simple boredom with travel, but not before concluding that he was,

obviously, a very unusual fellow.

He

was introduced to electricity, and thus, in a sense, to science at the

same early age; his father's superintendent, one Jean Pierre Gogen, gave

him a Leclanche wet battery, a piece of wire and an electric bell and showed

him how to hook them up. When the bell began ringing amid a shower of "wonderful

green sparks," Hugo instantly decided that he stood on the threshold of

a career worthy of his mettle.

He

was introduced to electricity, and thus, in a sense, to science at the

same early age; his father's superintendent, one Jean Pierre Gogen, gave

him a Leclanche wet battery, a piece of wire and an electric bell and showed

him how to hook them up. When the bell began ringing amid a shower of "wonderful

green sparks," Hugo instantly decided that he stood on the threshold of

a career worthy of his mettle.

He wasted not a single moment

in launching it. The boy sent off to Paris for a battery-actuated telephones

and six-volt light bulbs and, after electrifying the family estate to his

satisfaction, began contracting for similar jobs in the neighborhood. Business

success led as it sometimes does, to vice; he carried every newly earned

handful of francs to a poker game at Luxembourg's Grand Cafe and was cleaned

out by his elders every time.

A LIFELONG AFFAIR WITH

MARS

This

involvement with the gaming tables ended, however, as soon as he read Mars

by the American astronomer, Percival Lowell--a book which suggested that

Earth's sister planet supported green vegetation and perhaps even higher

forms of life. The prospect of sudden material gain, he discovered, was

not half so exciting as the idea that creatures like himself might inhabit

distant worlds.

This

involvement with the gaming tables ended, however, as soon as he read Mars

by the American astronomer, Percival Lowell--a book which suggested that

Earth's sister planet supported green vegetation and perhaps even higher

forms of life. The prospect of sudden material gain, he discovered, was

not half so exciting as the idea that creatures like himself might inhabit

distant worlds.

Gernsback was subjected to

rigorous bouts of education; he attended a French grammar school in Luxembourg,

moved on to a Brussels boarding school for instruction in languages and

then studied mathematics and electrical engineering for three years at

the Technikum in Bingen, Germany. He found time, nevertheless, to invent

the "most powerful dry cell battery in the world"--a stack of zinc and

carbon plates packaged in a salammoniac jelly which produced 375 amperes

and would melt a piece of metal as thick as a pencil. He read Mark Twain

too, listened to the music of John Phillip Sousa and pored over comic books

about the American "Wild West" which were popular in Germany at the time.

In the process he fell in love with the U.S. and determined to invade and

conquer it as soon as possible.

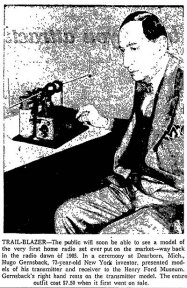

When his term of study at

Bingen was done, he bought a first class ticket to Hoboken on the Hamburg

American liner Pennsylvania, got himself a set of calling cards which identified

him as "Huck" Gernsback, bundled up two models of the most powerful battery

in the world, made a touch of $100 --his last--on the family exchequer

and set out to seek his fortune in the new world. The year was 1904. He

was 19. He spent $20 for a silk hat on the arrival in New York and, thus

equipped, was able to discover that the big city, as he had anticipated,

was an absolute pushover for a bright young man. He launched himself in

business by remodeling his dry cell and talking the Packard Motor Car Co.

into buying it for the ignition systems of their horseless carriages. In

the meantime he founded a little mail-order house, the Electro Importing

Company, and in three days of hard work designed a wireless sending and

receiving set (the world's first home), which sold for just $7.50 and caught

the public fancy in a matter of months.

He was able to afford Victor

Herbert musicals and dinners at Delmonico's from the beginning, and by

1910 needed 60 workmen and a factory on Fulton Street to satisfy the demand

for his radio set and the wide variety of condensers, spark coils, tuners

and other accessories his firm offered the amateur wireless telegrapher.

When the U.S. government banned amateur transmission during World War I,

he was stranded with $100,000 worth of useless tools and useless parts,

but extricated himself from financial disaster by an inspired blend of

craftiness and constructive though. He dashed off a handbook of heady information

on How To Make an Electric Fish ('One of the most mysterious tricks you

can perform!') and How to Build a Wireless Telephone (Show 'Ma' and 'Pa"

how you can actually talk through a brick wall!") and with this publication

on hand divided his heaps of contraband into "electric experimental kits"

for boys. The kits sold like hot cakes at $5 a throw--and made a profit

of 400%.

This ability to dominate

outrageous circumstance served to confirm a suspicion which Gernsback still

nurses--that nothing could be "easier than becoming a millionaire many

times over." Mere money-making bored him, however, and with honor satisfied

and capital retrieved he sold the Elecrtro Importing company and launched

himself wholeheartedly and for life as self-appointed front man, director,

scene arist and prompter for the unfolding drama of science and invention.

It

was a day when the physicist, the mathematician and even the astronomer

went almost completely unsung; Gernsback was motivated, in the main, by

a medicine-show barker's compulsion to yank them all out into the lamplight

to the accompaniment of banjo music, whether they liked it or not, and

to hold them up--not without certain mugging and cuff-shooting on his own

part--before the wondering world.

It

was a day when the physicist, the mathematician and even the astronomer

went almost completely unsung; Gernsback was motivated, in the main, by

a medicine-show barker's compulsion to yank them all out into the lamplight

to the accompaniment of banjo music, whether they liked it or not, and

to hold them up--not without certain mugging and cuff-shooting on his own

part--before the wondering world.

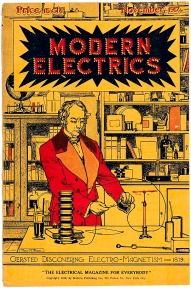

He was well prepared to do

so. His instinct for center stage and his bent for evangelism had already

prompted him to found a little monthly magazine called Modern Electrics

and he used it for a decade to thwack civilization onward toward destiny,

Gernsback, for instance, was the first man to conclude that the power and

wavelengths of radio stations would have to be regulated by the government

to prevent anarchy on the airwaves. Thanks to the vigor with which he called

this idea to congressional attention, one of his editorials on the subject

was adopted, almost word for word, as the Wireless Act of 1912, thus initiating

the whole present body of federal legislation on radio transmission. Also,

and more significantly by far, he wrote a serial for Modern Electrics entitled

Ralph 124C 41+, Thrilling Adventures in the Year 2660.

Ralph, which has been printed,

reprinted and then translated into French, German, and Russian during its

52 years, is still regarded with awe, and in some cases with active loathing,

by science fiction writers, editors and fans. It is Gernsback's contention

and that of his followers that genuine science fiction (it was Gernsback

who coined the term) must be scientifically feasible in all regards or

else it is mere fantasy. By this yardstick Ralph was the first major work

of science fiction, and all that went before and a great deal which has

followed is to be considered mere crabgrass in the lawn of verity. This

stiff-necked insistence on scientific validity is known among dissenters

in the trade as the "Gernsback Delusion."

To describe the book as a

novel is stretching the definition of that word to the screech-point. It

begins with the hero, Ralph 124C41+ (who possesses one of 10 gigantic minds

on Planet Earth) rescuing beautiful Alice212B 423 from an avalanche, simply

by turning up the juice in his Manhattan power mast and melting the Alpine

snows with long-distance heat waves. The book's tone and dialogue are reminiscent

of Tom Swift and His Electric Runabout, its plot is illogical and the level

of writing to be encountered in it is, to quote the author himself, "simply

awful."

All this, however, is only

critical niggling. Ralph 124C 41+ was whacked together simply as a vehicle

for scientific prediction, and as such it is an astonishing performance.

Gernsback's description of radar is probably the book's most brilliant

stroke, but it also accurately prophesied advances in dozens of other new

fields: fluorescent lighting, sky writing, plastics, automatic packaging

machines, tape recorders, liquid fertilizer, stainless steel, loudspeakers,

night baseball, microfilm, synthetic fabrics and even flying saucers.

A great many attitudes about

science which were held in the U.S. during the 1920s, '30s, '40s and even

throughout the early 1950s stemmed, if only subconsciously, from science

fiction and it is difficult not to feel that they all had their beginnings

in Ralph 124C41+ and in Gernsback's unbridled enthusiasm for the medium.

It would doubtless be incorrect to suggest that Buck Rogers, motion picture

space queens and box-top disintegrator guns would not have evolved without

him, but all of them in fact germinated in a thick mulch of Martians, space

ships, galactic empires and robots which Gernsback troweled into his early

magazines.

In his decades of attempting

to gauge the public temper and captivate, and occasionally browbeat the

public mind, Gernsback has never hesitated to kill going magazines and

to found new ones. Over the years, as a result, he has published literally

dozens of them--including, at one point, a monthly called Coocoo-Nuts devoted

to translating well-known sayings and clichés into funny illustrations.

Most of his publications, however, have been technical by nature. In the

beginning he leavened them continually with tales of space ships and distant

worlds. But in 1926 he founded Amazing Stories, the first magazine devoted

entirely to what he then described as "scientifiction" and the one which--simply

by succeeding and fostering imitators--popularized the form and thus, in

its own hyperthyroid fashion, forecast the fantastic realities of the Space

Age.

It is doubtful that any single

scientific work has so influenced science fiction--although this was not

Gernsback's purpose in buying and publishing it--as a three-part article

entitled "The Problems of Space Flying" which he ran in Science Wonder

Stories in 1929. Very few Americans are aware, even today, that basic concepts

of space travel now being applied by the U.S. and the Soviet Union were

worked out in detail by a German scientist named Hermann Oberth during

the 1920s. Gernsback, as a prodigious reader of German scientific publications,

followed his career with vast excitement and managed to talk one of the

physicist's disciples into writing a long dissertation on the master's

concepts.

"The Problems of Space Flying"

begins with a discussion of weightlessness--assuring the reader that humans

can endure it for long periods, though at the risk of atrophy of important

muscle systems in the body. It describes the behavior of liquids during

free fall and suggests--since water escaping from a bottle would float

about in spherical form--that food and drink be served in squeeze packages.

It discusses orbital rendezvous, methods of building a space station and

giving it an artificial gravity, the need of reflective surface painting

to heat and cool space vehicles, and the means of generating electricity

from solar heat. It describes space suits, problems of re-entry into the

earth's atmosphere, methods of celestial navigation, time tables for trips

to the nearer planets (Venus, 146 days; Mars 235), and the advantages to

be derived from placing fuel depots and launching stations on the moon.

AN ORBITING MIRROR TO

FRY THE ENEMY

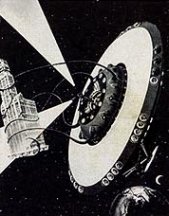

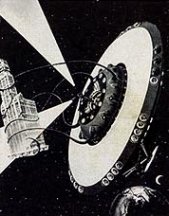

It

does not overlook the civil and military benefits which could accrue to

a nation with a strong position in space. Oberth strongly advocated construction

of an orbital mirror 60 miles in diameter. This devise, with a surface

composed of thousands of movable, shutterlike panels, would by his calculations

have needed 15 years of work and the expenditure of $750 million for development.

But the nation which owned it, he predicted, could control sunlight, and

therefore weather, could eliminate night over big areas of countryside

and also, with a few quick adjustments, burn its enemies to a crisp.

It

does not overlook the civil and military benefits which could accrue to

a nation with a strong position in space. Oberth strongly advocated construction

of an orbital mirror 60 miles in diameter. This devise, with a surface

composed of thousands of movable, shutterlike panels, would by his calculations

have needed 15 years of work and the expenditure of $750 million for development.

But the nation which owned it, he predicted, could control sunlight, and

therefore weather, could eliminate night over big areas of countryside

and also, with a few quick adjustments, burn its enemies to a crisp.

Gernsback dealt severely

in his own articles with those who he felt were scientific pretenders.

He looked with doubt on famed H. Grindell Matthews for "claiming" to have

invented a death ray, noting acidly that "the possibility of Matthews having

discovered a ray not known to the editor of this magazine is very slight."

On the other hand, he allowed his imagination, and that of others, full

swing, if he felt there was the slightest basis in fact to support a scientific

premise. He was delighted, in 1920, to quote England's Sir Oliver Lodge

on the "prodigious forces" inherent in the atom-- "there is enough energy

in one ounce of coal to raise the German fleet from the bottom of Scope

Flow and pile it on the Scottish Mountains." He was, and still is, fascinated

by the idea of gravity-nullifying devises and ran a "city the size of New

York" floating, apparently on a large platter, high above the earth "where

the air is purer and free of disease-carrying bacteria."

His childhood enchantment

with Mars left him with an enormous, sentimental regard for that planet

and he has felt a constant compulsion to get in touch with it. As early

as 1909 he advocated hooking all the wireless stations in the U.S. to one

central key located in Lincoln, Nebraska and sending a super signal to

alert the Martians-- a race of beings he seemed to feel ought to exist

even if they didn't-- to the Earth people's interest in them. Eleven years

later he published the details of another plan; blinking code messages

into space with a battery of 1,000 powerful searchlights. He also invented

a Martian--a tall, skinny, birdlike creature--who has been copied by cartoonists

and illustrators ever since.

Gernsback's Martian has long

since served his purpose--to startle and stir people who thought of Mars

only as a remote point of red light in the eastern sky--and now he must

be considered as extinct as the moon maidens and long-bearded Venusian

seers who were his companions on the pages of forgotten pulp magazines.

Time eroded the stuff of many another Gernsback prophecy and has taken

many a scientist whose career he tracked and dramatized. Lee DeForest,

who shopped at the Electro Importing Company for materials with which he

developed the vacuum tube, is long gone. So is the great Nikola Tesla,

who gave the world alternating current and wore shoes with wooden pegs

because of his fear of it. The death mask of Tesla which Gernsback commissioned

and now keeps in his office is the sole monument raised to the electrical

genius in the U.S. Dr. Alfred C. Kinsey, with whom Gernsback collaborated

and broke bread in the early 1950s, is, too, only a name.

The considerable list of

Gernsback's own inventions sounds quaint and archaic--the "Radiotrola"

(first radio console with a loop aerial), the "Staccotone" (a radio piano),

several obscure types of electronic circuitry and the "Osophone" (his bone-conduction

hearing aid-- which unfortunately helped only those willing to walk around

with a microphone in one hand and a hard rubber mouth-piece between their

teeth).

The

tele-numbed 1960s make his laborious, excited and splendidly bull- headed

1928 telecasting seem more archaic yet. The devise by which Station WRNY

emitted its primitive video signals--a whirling perforated "scanning disc"

hooked to a set of photoelectric cells--produced a picture only one and

a half inches square. Programs simply showed the head and shoulders of

a singer, a speaker or a doll which was sometimes used as a substitute

subject. They could be received in all New York by only a dozen or so rabid

"experimenters" who had built similar disc machines from instructions in

one of Gernsback's own magazines, Radio News. But those telecasts dramatized

his own tenacity more pointedly than the process dramatized the inevitability

of image by wireless.

The

tele-numbed 1960s make his laborious, excited and splendidly bull- headed

1928 telecasting seem more archaic yet. The devise by which Station WRNY

emitted its primitive video signals--a whirling perforated "scanning disc"

hooked to a set of photoelectric cells--produced a picture only one and

a half inches square. Programs simply showed the head and shoulders of

a singer, a speaker or a doll which was sometimes used as a substitute

subject. They could be received in all New York by only a dozen or so rabid

"experimenters" who had built similar disc machines from instructions in

one of Gernsback's own magazines, Radio News. But those telecasts dramatized

his own tenacity more pointedly than the process dramatized the inevitability

of image by wireless.

Television constitutes but

one stream in the flood of innovation which recently has threatened to

wash Gernsback out of existence; the whole of science, in fact, has risen

and gone roaring past him since the discovery of nuclear fission and the

beginnings of the space race, and the placid little backwaters which he

breasted as a young man have been lost forever beneath the torrent. He

seems delighted by the whole phenomenon. "My only reaction is this," he

says--"What took them so long?" But he still works at his self- appointed

mission as intently as a prospector seeking the mother lode.

Food and wine are his only

non-scientific interest, and the only hours of real relaxation he allows

are spent at the most posh Manhattan restaurants. He arrives at his spacious,

old-fashioned office in New York's Greenwich Village, dressed to the nines,

by 8:30 every morning, and he sits up late in his handsome apartment overlooking

the Hudson River reading piles of scientific publications. He goes over

then with a beady eye, alert for the stuff of new predictions. Error--even

if he chances to detect it in so lowly a medium as a comic strip--fills

him with indignation. On finding a comic- page character floating in the

infinite without a space suit recently, he cried, "Wrong! His internal

pressure would exceed the external pressure. His eyes would pop out! His

belly would swell out! He would blow up!"

He has abandoned all involvement

with science fiction, now so overshadowed by fantastic reality, and published,

with his book list, but two magazines: Radio electronics, the "bible" of

television repair men, and the curious little monthly Sexology. Gernsback

supports Sexology fiercely; with physics and the delights of space travel

now being pawed over by armies of newcomers, he feels that sex offers a

last, unexplored, scientific frontier.

Gernsback is fully prepared,

even anxious, to answer the slavering critic who accuses him of prurience..

Sex, he feels, is a "cultural subject" and as such should not be "relegated

to back rooms" but discussed openly--even its more peripheral phases. He

finds the "non-scientific attitude" about it "appalling, abysmal stupidity....Let

me tell you something very few people realize," he says. "Even physicians

are not taught anything about sex in college! A horrifying situation!"

Sex has not distracted him

in the slightest, however, from his lifelong interest in electronic gadgetry

and in the new horizons being opened by the advance of more orthodox scientific

knowledge. Neither has it inhibited his bent for invention on those occasions

when he feels that duty and circumstance demand it--although he now invents

only in broad outline, leaving the actual mechanics of the thing to others.

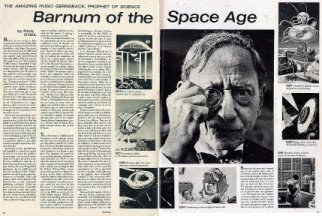

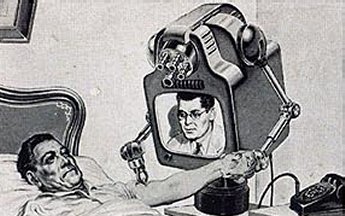

His television eyeglasses--a device for which he feels millions yearn--constitute

a case in point.

When the idea for this handy,

pocket-size portable TV set occurred to him in 1936, he was forced to dismiss

it as impractical. But a few weeks ago, feeling that the electronics industry

was catching up with his New-Deal era concepts, he ordered some of his

employees to build a mock-up.

"It is now perfectly possible

to make thin, inch-square cathode tubes," he says, "and to run them with

low-voltage current from very small batteries with no danger at all of

electrocuting the wearer. Sound can be carried to the ear just as a hearing

aid. Television eyeglasses should weigh only about five ounces. Since there

will be a picture for each eye, the glasses will make a stereoptical view

possible and since they will be masked--like goggles--they can be used

in bright sunlight. The user can take them out of his pocket any where,

slip them on, flip a switch and turn to his favorite station." A V-type

aerial protrudes from the top of Gernsback's mock-up of the TV glasses.

he likes the effect--which can only be described as neo-Martian.

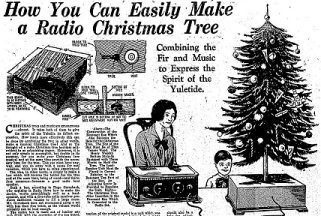

Amidst

these preoccupation's Gernsback also plans, writes, edits and makes up

a gaudily illustrated pocket-size booklet called Forecast, which he mails

out annually at Christmas to 9,000 people--a great proportion of them newspaper

and periodical editors and writers, scientists and executives in electronic

industries--who may not necessarily have availed themselves of the opportunity

to follow his thinking during the year. A certain amount of publicity accrues

to him because of Forecast, which is now in its 29th year, but more importantly

it allows him to keep the minds of influential men and women properly adjusted

to the Gernsback view--something, no human alive is capable of achieving

without assistance from Gernsback.

Amidst

these preoccupation's Gernsback also plans, writes, edits and makes up

a gaudily illustrated pocket-size booklet called Forecast, which he mails

out annually at Christmas to 9,000 people--a great proportion of them newspaper

and periodical editors and writers, scientists and executives in electronic

industries--who may not necessarily have availed themselves of the opportunity

to follow his thinking during the year. A certain amount of publicity accrues

to him because of Forecast, which is now in its 29th year, but more importantly

it allows him to keep the minds of influential men and women properly adjusted

to the Gernsback view--something, no human alive is capable of achieving

without assistance from Gernsback.

Each issue of this little

annual contains references to his past and his more spectacular predictions--into

which certain overtones of self congratulation sometimes creep--so that

even the newest reader is not left in doubt as to its publisher's identity

and place in the scheme of things. Forecast's major function, however,

is the dissemination of Gernsback's latest predictions, and his latest

and most vehement opinions on the state of science and of civilization.

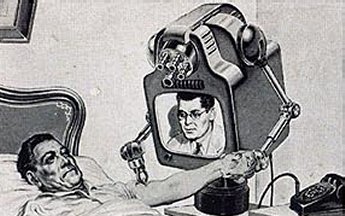

He feels certain, for instance,

that the "doctor shortage" is nonsense or could be quickly solved, at any

rate, if only patients were equipped with "medi-wrist radio transmitters,"

which would send temperature, pulse rate, respiration and other clues as

to their condition to a central monitoring station.

HIS LATEST SCHEME: MINING

THE MOON

Neither

the size, cost, nor the impressive achievements of the U.S. space program

prevent his giving NASA occasional advise. It is his opinion that the U.S.

should immediately cease this "senseless" orbiting of the earth with manned

space capsules--since the Russians, in effect, have already done it for

us--and get on the moon with all dispatch. In a recent issue he worked

out plans for the transport of metals from the moon after it is explored

and after mining camps have been set up there to exploit its "fantastic

mineral riches." Two-way traffic will, in his view, be unnecessary. Moon

colonists, if they are wise, will simply construct 50-foot, spherical,

unmanned, one-way space ships of valuable beryllium, load them with 300

tons of gold and lob them into one of earth's oceans. Since each beryllium

ship would float, it could easily be retrieved and, after removal of the

fold, be melted down for use on earth. Total profit per ship-trip; $606

Million.

Neither

the size, cost, nor the impressive achievements of the U.S. space program

prevent his giving NASA occasional advise. It is his opinion that the U.S.

should immediately cease this "senseless" orbiting of the earth with manned

space capsules--since the Russians, in effect, have already done it for

us--and get on the moon with all dispatch. In a recent issue he worked

out plans for the transport of metals from the moon after it is explored

and after mining camps have been set up there to exploit its "fantastic

mineral riches." Two-way traffic will, in his view, be unnecessary. Moon

colonists, if they are wise, will simply construct 50-foot, spherical,

unmanned, one-way space ships of valuable beryllium, load them with 300

tons of gold and lob them into one of earth's oceans. Since each beryllium

ship would float, it could easily be retrieved and, after removal of the

fold, be melted down for use on earth. Total profit per ship-trip; $606

Million.

Gernsback does not arrive

at the sum of the year's augury for Forecast without steady, month-by-month

cerebration. He is not, in fact, above wishing that the electronic-brain-with-memory-cells

which he recently forecast were already in being to give him occasional

assistance. His expression, in its absence, is habitually grim. "Mr. Gernsback,"

says a merchant on Manhattan's West 14th Street who has watched the prophet

heading for his office every morning for years, "always looks as though

he is carrying the world on his shoulders." The statement needs only minor

editing. For complete accuracy delete "always looks as though" and replace

"world" with "our planetary system."

Gernsback,

in fact, has felt himself impelled to preach the gospel of science ever

since his youth in Luxembourg--not so much, apparently, for the good of

science as for his own satisfaction and the delights of seeing his name

in the papers. In 55 years as a self-appointed missionary, he has stiffly

ignored both the cackling of the heathen and the cries of competing apostles.

Moreover, as founder, owner, and guiding spirit of Gernsback Publications,

Inc., a New York-based publishing enterprise which has produced a succession

of scientific and technical books and magazines (among themAmazing Stories,

the first science-fiction monthly), he has not only provided himself with

a method of firing endless barrages of opinion, criticism and augury but

the means of making a good deal of money as well.

Gernsback,

in fact, has felt himself impelled to preach the gospel of science ever

since his youth in Luxembourg--not so much, apparently, for the good of

science as for his own satisfaction and the delights of seeing his name

in the papers. In 55 years as a self-appointed missionary, he has stiffly

ignored both the cackling of the heathen and the cries of competing apostles.

Moreover, as founder, owner, and guiding spirit of Gernsback Publications,

Inc., a New York-based publishing enterprise which has produced a succession

of scientific and technical books and magazines (among themAmazing Stories,

the first science-fiction monthly), he has not only provided himself with

a method of firing endless barrages of opinion, criticism and augury but

the means of making a good deal of money as well.

This

admiration is solidly based. Gernsback, in his unique career, has not only

done his best to prepare the public mind for the "wonders" of science but

has sometimes managed to tell science itself just what wonders it was about

to produce. for instance, he conceived the essential principles of radar

aircraft detection in 1911--a year when the airplane itself was barely

able to stagger off the ground. This early concept was so complete that

Sir Robert Watson-Watt, whose radar tracking devices helped save London

in the Battle of Britain, considers him the original inventor.

This

admiration is solidly based. Gernsback, in his unique career, has not only

done his best to prepare the public mind for the "wonders" of science but

has sometimes managed to tell science itself just what wonders it was about

to produce. for instance, he conceived the essential principles of radar

aircraft detection in 1911--a year when the airplane itself was barely

able to stagger off the ground. This early concept was so complete that

Sir Robert Watson-Watt, whose radar tracking devices helped save London

in the Battle of Britain, considers him the original inventor.

It

is, therefore, difficult not to believe that U.S. science has been influenced

in many ways as a result of Gernsback's extraordinary career in evangelism;

certainly it has absorbed a flavor, unobtainable by any other means, simply

through harboring him in its midst, like a peppercorn in a pudding, for

a full half-century. The effect, however, would hardly have been achieved

were it not for a certain duality in Gernsback's nature. While he is cuckoo

for science and takes a Barnum like joy in the bizarre (he is so proud

of having invented a device for hearing through the teeth that he has listed

it in Who's Who), he is also a man of real intellect in whose mind are

mated astonishing scientific intuition, an instinct for command and a shrewd

if exotic sense of business.

It

is, therefore, difficult not to believe that U.S. science has been influenced

in many ways as a result of Gernsback's extraordinary career in evangelism;

certainly it has absorbed a flavor, unobtainable by any other means, simply

through harboring him in its midst, like a peppercorn in a pudding, for

a full half-century. The effect, however, would hardly have been achieved

were it not for a certain duality in Gernsback's nature. While he is cuckoo

for science and takes a Barnum like joy in the bizarre (he is so proud

of having invented a device for hearing through the teeth that he has listed

it in Who's Who), he is also a man of real intellect in whose mind are

mated astonishing scientific intuition, an instinct for command and a shrewd

if exotic sense of business.

He

was introduced to electricity, and thus, in a sense, to science at the

same early age; his father's superintendent, one Jean Pierre Gogen, gave

him a Leclanche wet battery, a piece of wire and an electric bell and showed

him how to hook them up. When the bell began ringing amid a shower of "wonderful

green sparks," Hugo instantly decided that he stood on the threshold of

a career worthy of his mettle.

He

was introduced to electricity, and thus, in a sense, to science at the

same early age; his father's superintendent, one Jean Pierre Gogen, gave

him a Leclanche wet battery, a piece of wire and an electric bell and showed

him how to hook them up. When the bell began ringing amid a shower of "wonderful

green sparks," Hugo instantly decided that he stood on the threshold of

a career worthy of his mettle.

This

involvement with the gaming tables ended, however, as soon as he read Mars

by the American astronomer, Percival Lowell--a book which suggested that

Earth's sister planet supported green vegetation and perhaps even higher

forms of life. The prospect of sudden material gain, he discovered, was

not half so exciting as the idea that creatures like himself might inhabit

distant worlds.

This

involvement with the gaming tables ended, however, as soon as he read Mars

by the American astronomer, Percival Lowell--a book which suggested that

Earth's sister planet supported green vegetation and perhaps even higher

forms of life. The prospect of sudden material gain, he discovered, was

not half so exciting as the idea that creatures like himself might inhabit

distant worlds.

It

was a day when the physicist, the mathematician and even the astronomer

went almost completely unsung; Gernsback was motivated, in the main, by

a medicine-show barker's compulsion to yank them all out into the lamplight

to the accompaniment of banjo music, whether they liked it or not, and

to hold them up--not without certain mugging and cuff-shooting on his own

part--before the wondering world.

It

was a day when the physicist, the mathematician and even the astronomer

went almost completely unsung; Gernsback was motivated, in the main, by

a medicine-show barker's compulsion to yank them all out into the lamplight

to the accompaniment of banjo music, whether they liked it or not, and

to hold them up--not without certain mugging and cuff-shooting on his own

part--before the wondering world.

It

does not overlook the civil and military benefits which could accrue to

a nation with a strong position in space. Oberth strongly advocated construction

of an orbital mirror 60 miles in diameter. This devise, with a surface

composed of thousands of movable, shutterlike panels, would by his calculations

have needed 15 years of work and the expenditure of $750 million for development.

But the nation which owned it, he predicted, could control sunlight, and

therefore weather, could eliminate night over big areas of countryside

and also, with a few quick adjustments, burn its enemies to a crisp.

It

does not overlook the civil and military benefits which could accrue to

a nation with a strong position in space. Oberth strongly advocated construction

of an orbital mirror 60 miles in diameter. This devise, with a surface

composed of thousands of movable, shutterlike panels, would by his calculations

have needed 15 years of work and the expenditure of $750 million for development.

But the nation which owned it, he predicted, could control sunlight, and

therefore weather, could eliminate night over big areas of countryside

and also, with a few quick adjustments, burn its enemies to a crisp.

The

tele-numbed 1960s make his laborious, excited and splendidly bull- headed

1928 telecasting seem more archaic yet. The devise by which Station WRNY

emitted its primitive video signals--a whirling perforated "scanning disc"

hooked to a set of photoelectric cells--produced a picture only one and

a half inches square. Programs simply showed the head and shoulders of

a singer, a speaker or a doll which was sometimes used as a substitute

subject. They could be received in all New York by only a dozen or so rabid

"experimenters" who had built similar disc machines from instructions in

one of Gernsback's own magazines, Radio News. But those telecasts dramatized

his own tenacity more pointedly than the process dramatized the inevitability

of image by wireless.

The

tele-numbed 1960s make his laborious, excited and splendidly bull- headed

1928 telecasting seem more archaic yet. The devise by which Station WRNY

emitted its primitive video signals--a whirling perforated "scanning disc"

hooked to a set of photoelectric cells--produced a picture only one and

a half inches square. Programs simply showed the head and shoulders of

a singer, a speaker or a doll which was sometimes used as a substitute

subject. They could be received in all New York by only a dozen or so rabid

"experimenters" who had built similar disc machines from instructions in

one of Gernsback's own magazines, Radio News. But those telecasts dramatized

his own tenacity more pointedly than the process dramatized the inevitability

of image by wireless.

Amidst

these preoccupation's Gernsback also plans, writes, edits and makes up

a gaudily illustrated pocket-size booklet called Forecast, which he mails

out annually at Christmas to 9,000 people--a great proportion of them newspaper

and periodical editors and writers, scientists and executives in electronic

industries--who may not necessarily have availed themselves of the opportunity

to follow his thinking during the year. A certain amount of publicity accrues

to him because of Forecast, which is now in its 29th year, but more importantly

it allows him to keep the minds of influential men and women properly adjusted

to the Gernsback view--something, no human alive is capable of achieving

without assistance from Gernsback.

Amidst

these preoccupation's Gernsback also plans, writes, edits and makes up

a gaudily illustrated pocket-size booklet called Forecast, which he mails

out annually at Christmas to 9,000 people--a great proportion of them newspaper

and periodical editors and writers, scientists and executives in electronic

industries--who may not necessarily have availed themselves of the opportunity

to follow his thinking during the year. A certain amount of publicity accrues

to him because of Forecast, which is now in its 29th year, but more importantly

it allows him to keep the minds of influential men and women properly adjusted

to the Gernsback view--something, no human alive is capable of achieving

without assistance from Gernsback.

NEW

YORK (UPI) - Who is ahead in the space race? Forget about Russia and the

United States. They're way behind.

NEW

YORK (UPI) - Who is ahead in the space race? Forget about Russia and the

United States. They're way behind.