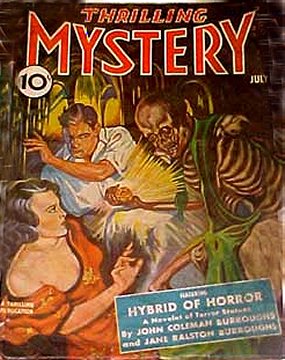

Hybrid

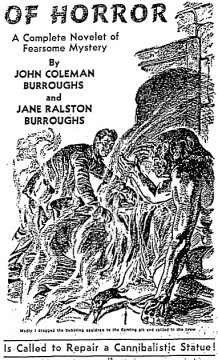

Of Horror

A

Complete Novelet of Fearsome Mystery

by

John

Coleman Burroughs

and

Jane

Ralston Burroughs

Chapter

II: Master of the Manor

The man bowed low, in apelike

mimicry of an ancient human greeting.

"Good evening, David Renton.

I welcome you to the cozy hospitality of Gribold Manor."

I drew back involuntarily.

Speech shouldn't have flowed so easily from the mouth of an atavism like

that. And his breath! God, it was as fetid as though he had been dead for

centuries.

A cross between a snarl and

a frozen smile lifted the corner of his flabby mouth, revealing a dirty,

yellow fang. I was immediately struck by the prominence of the supra orbital

ridges and the short, receding forehead -- the indication of an extremely

thick skull. His round, owl-like eyes gleamed like twin holes into hell.

The short cane he grasped in one hairy hand seemed to be fashioned of some

greenish stone. It had been broken, leaving a wicked, jagged end.

"I trust you enjoyed my concert,

Mr. Renton?" the rasping voice went on. "I often have them, much to the

discomfort of my splendid servant here."

Rakor Gribold shuffled over

to Mason, and poked him with his cane.

"Get up and take our guest's

bags to his room, you stupid fool! What do I pay you for -- to sleep on

the floor?" Mason cowered as the giant, bearded figure of the Master of

Gribold threatened him with his boot.

"Gribold," I interrupted, "if

you don't mind, I'd like to see the statue you want me to repair."

I found myself struck with

a strong desire to get the job over, collect that extra thousand, and get

out. Gribold came close to me again. He blew in my face and grinned. Then

he shuffled off sown the hallway.

I took a thick tallow from

a nearby stand, lit it, and followed Rakor Gribold down into the dungeons.

Tortuous winding corridors

led ever downward. The air was damp with the chill of a lonely grave. Strange

noises whirred through the hanging moss and roots. Bats, I thought. Carefully

I shaded the candle with my hand.

I slipped suddenly. The candle

fell, rolled away into a tunnel off the main corridor. I cursed, wiped

the slime from my clothes and groped after the flickering light. It had

rolled against the rusty bars of a tiny cell.

I clutched the tallow firmly

and turned to go on. Out of the corner of my eye I caught a glimpse of

something white. I swung around, held the candle high. Mutely staring down

at me was the bleached skull of some long dead human There came a mirthless

chuckle behind me. Gribold was fingering his necklace of teeth.

"An ancient enemy of the Gribolds,"

he purred. "It was an exquisite torture. They hung him on the wall -- very

carefully, so he wouldn't strangle. Then they covered his body with molasses.

Our little friends did the rest."

Gribold pointed to the walls

and beams supporting the roof of the tunnel. They were covered with a pulsing

blackness. I drew back as something fell on my hand. I brushed it off,

crushed it under my heel. It was a shiny, black cockroach!

Gribold slashed at the beauty

of a fragile moss-flower with his broken cane.

"Of course, Mr. Renton, you

realize that this was done in centuries past. We don't think of doing those

things in this day."

He moved to the main corridor.

I followed, noting with relief that the tremendous beams and the supporting

walls of the main tunnel were free of the repulsive insects. But each side

tunnel seemed to move with a hideous life of its own. Now and then flickering

lights would start and disappear in the murky darkness.

The cobblestones under my feet

had been worn into a trough like path by Gribold's ancestors. The hollows

between the stones were filled with puddles of black water that blinked

up like evil eyes as the light of the candle glanced over them.

There was a sharp turn and

the corridor ended. Rakor Gribold stood before a huge iron door. He fumbled

under his thick robe, drew forth a key, fitted it into the lock. It was

then that I noticed the curiously voluminous clothing that covered him

from neck to foot.

The door moved slowly inward,

sighing as though it were eternally weary of being opened and shut.

When Rakor Gribold entered

the chamber, I felt an urge to turn and run. The evil that poured out of

the room was as potent as the smell.

Then I saw the pit.

It was in the center of the

floor. From its cavernous depths billowed red flames and a sickening odor

that I can compare only to burning flesh. Boiling sluggishly in a massive

iron pot hanging over the pit was a nauseous mass that gurgled and belched

green fumes.

Suspended from chains that

disappeared into a seemingly endless ceiling were a dozen bleached skeletons.

They swung, still articulated, on giant hooks. I shrank from the wanton

torture that must have taken place there.

The room was so dry that it

almost crackled. Feeling a peculiar roundness under my feet, I looked down.

I drew in my breath. The floor was paved with human skulls! Hell would

have a floor like this.

Carved in the nearest wall

were symbols of the Black Arts, and a map of forgotten secrets of the Gribold

blood cults. Old musty books stood on a shelf -- black books of the Faith's

Kingdom.

Again my eyes were drawn to

the cauldron. Through the smoke and flames I thought I saw a figure bent

over the boiling mass. A witchlike thing stirred the brew with a human

leg bone! I had a confused glimpse of red glaring eyes, matted hair, incredibly

wrinkled skin, a loose mouth moving over stained fanged teeth. But even

as I peered closer, the figure seemed to dissolve. I reasoned that the

smoke from the pit and the steam from the brew had caused an optical illusion.

Rakor Gribold was lighting

giant candles at one end of the room. He stepped aside.

I quickly joined him at the

base of a thronelike pedestal. I looked up, gasped! Before me crouched

the famous Statue of Gribold!

Never had I seen such realism

used to depict so fantastic a subject. It looked human, but the hideous

grotesqueness of the thing made the human qualities uncanny. If it were

standing, I judged it would be about the size if Rakor Gribold. The torso

and legs were human. But the features were so insanely cruel that I found

myself marveling at the hands that had modeled them. I saw some intangible

expression, perhaps a similar facial angle, that reminded me of the bearded

Rakor Gribold.

The creature on the pedestal

had four arms. Two were short and two were long. ONe of the long arms had

been broken off at the elbow. Gribold pointed to the broken joint.

"This is why I needed you,

a sculptor, to mend my little pet."

He stroked the hideous head

as though he were caressing his dog. I examined the broken stub.

"How was the arm broken?" I

naturally asked. "Do you have the piece?"

My answer was a crooked smile

from the Master of Gribold Manor.

"Tomorrow you will start to

work," he said. "It will be quite cozy for you down here. But of course

you will have to work by oil light."

I was about to protest. Working

by oil light in a smelly dungeon would be a hardship for any artist, but

for two thousand dollars I could endure it. I'd repair the Statue's arm

twice as fast as any other sculptor could, and beat it away from that fantastically

horrible place.

As we left the dungeon, I caught

sight of Mason scurrying around a sharp turn of the corridor. A fierce

light flared up in Gribold's eyes. I saw that yellow fang bared again.

My room was on the second floor

at the head of the stairs. I was tired and scarcely noticed much about

it when I climbed into the huge old bed. I did remember to lock the door,

however.

The clock at the foot of the

stairs bonged twice. I awoke with a start, listening intently.

There was a soft shuffling

just outside my door. I sprang from my bed, flipped the lock and yanked

the door open.

Mason was standing there, like

a frightened dog.

"They're starin' at me again,

Gov'nor. Borin' into me. Just like they do every night!" He clutched at

my arm. "Can't yer do something? Make 'em stop?"

In an attempt to quiet the

fellow, I drew him into the room and closed the door. I shook his arm.

"What's staring at you?" I

asked.

"Hit's 'is eyes again -- They're

tryin' to make me go down to that dungeon," Mason whispered fiercely in

my ear. "To that place in the basement where that statue is. Keep me in

here, Gov'nor. Don't let me go!"

The fellow seemed sincere enough

in his belief that Gribold's eyes were hypnotizing him. I didn't have the

heart to make him go down again to his lonely room off the kitchen.

The remainder of the night

I listened to Mason's explosive snores and pondered over the man's strange

terror. I found myself becoming aware of that same sensation of being watched

by someone unseen. Only in this case it was my very thoughts that seemed

to be under cold scrutiny by some hidden evil force.

I attributed the feeling to

Mason and the power of suggestion. Finally, just as the first rooster was

awakening, I fell asleep.

That morning at breakfast,

the iron knocker banged on the front door. Its thunder reverberated through

the manor, rousing all the dormant echoes from the dungeons. I felt sure

that I could never accustom myself to that frightful din.

Mason, still worried, came

in a moment later.

A man to see yer, Gov'nor.

'E said 'e'd wait outside."

Puzzled, I went to the front

door. I saw a wizened man with ferret eyes, pulling impatiently at

a large black mustache.

"Follow me," the man said crisply

in a cracked voice.

I followed him obediently out

the door. When we were some distance from the manor he stopped.

"I'm the sheriff from Gribold

village' he barked. Then he dug a bony paw into his coat pocket and pulled

out a small automatic, cold and blue. "Take it," he said suddenly.

Surprise must have been evident

on my face as I took the gun. The sheriff conjured a water-logged toothpick

from behind a golden facade of dentistry and blew it into space.

"That gun," he remarked. "Yuh

can't kill nothin' much with it -- but yuh can use it to call me up here

with!"

The sheriff next produced a

package of gum. He undressed each piece and stuffed them all into his mouth.

Then he dabbed at his bald head with a pink handkerchief.

"I dunno what yer business

is here," he said, after a pause. "An' I don't say as I give a damn. But

I ain't hankerin' to have any more people around here showin' up vanished!"

I still must have appeared

unconscious of what he was driving at, but he kept right on chewing and

talking.

"Shoot that gun off I give

yuh three times if yuh need me, son, an' don't ferget it. I'll hear it

down at the office an' hot-foot right up here."

"I don't understand," I finally

managed. "Why should I need you?"

"They's legends," he said,

"among the villagers an' farmer folk 'bout this place. They says the Gribolds

has always been meat eaters. It's part o' their religion, an' well -- some

of the stories is pretty goll durned screwy. Others? I dunno. I'm sheriff.

I'm supposed to deal in facts."

The sheriff paused to adjust

his cud of gum.

"All I know is people come

into this place and they don't never come out. Farmers are murdered hereabouts

or they just disappear. I've come up here umpty-nine times with warrants,

questioned Gribold an' tried to search the damn place. But all I can ever

find is rats, cockroaches and a thousand smells. So this is just in case.

The sheriff peered about the

gardens to make sure we were still alone. Then he drew out a red bandanna

tied into a sack. He dumped out on his hand what looked like some green

pieces of stone.

"In the dead o' night, a week

back,' he whispered, "a farmer down yonder, 'Plow' Hendricks they call

him, woke up to see somethin' peerin' at him through the window. He grabbed

his shotgun and blasted away. The critter, whatever it was, beat it. But

here's a queer thing about it." The sheriff bounced the greenish pieces

of stone in his hand. "I found these goll durned things all over the ground

by that farmer's window!"

I took some of the pieces and

examined them closely. What at first I had taken to be a green igneous

stone now looked like some soft plastic material that had hardened.

"Ever notice anything like

that around in the manor?" the sheriff questioned.

I shook my head and handed

him back the pieces. He wrapped them up again carefully in his bandanna

and slipped the sack into his pocket.

"I just wondered," he said.

"I'll be leavin' now. Watch yourself, son, an' remember them three shots

if yuh need me.

"That farmer," I asked quickly,

just as he turned to go. "Was he able to describe what he had seen looking

in at him that night?"

"Well, yeah," admitted the

sheriff. "But every prowler 'round these parts fits the same description

-- like it's allus been since I was a kid an' my ole man afore me."

"What description?"

"Just as Plow Hendricks said,

the critter he seen lookin' in at him had four arms!"

I slipped the automatic into

my coat pocket. The sheriff turned and ambled off down the trail toward

the village.

The Authors

John

Coleman and Jane Ralston Burroughs

.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()