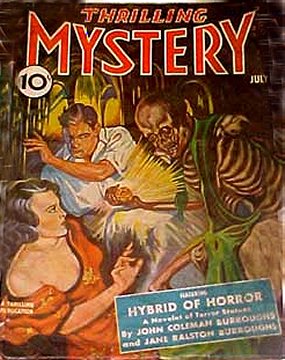

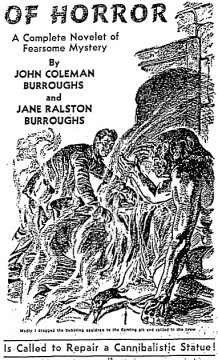

Hybrid

Of Horror

A

Complete Novelet of Fearsome Mystery

by

John

Coleman Burroughs

and

Jane

Ralston Burroughs

Chapter

III: The Fearful Workroom

Rakor Gribold

was waiting for me at the door. We went immediately to the dungeons. I

saw that Gribold had set up some oil lanterns around the statue. They illuminated

the crouching figure, but only served to make the surrounding darkness

more Stygian.

Rakor

Gribold stood by with folded arms while I made a careful examination of

the statue. As I had suspected the night before, it was not chiseled stone.

It seemed to be a composition what I was completely unfamiliar with. The

arm should be repaired with the same material. Gribold moved over to the

cauldron.

"This

is what you will need," he said, anticipating my question.

He brought

an iron dish filled with some of the substance from the cauldron. It was

a remarkably light plastic, and of the same greenish hue as the statue

-- and strangely like the greenish pieces of stone the sheriff had picked

up. I hardened and modeled easily.

I found

it impossible to become absorbed in my work. LIke an unclean servant of

Belial, Rakor Gribold hung over my shoulder. His rancid panting irritated

me almost beyond endurance. He scarcely spoke a word, merely grunting with

satisfaction as the work progressed. His eyes continually feasted on the

hideous statue. He caressed it, drooled on its squat hand.

The murky

chamber, the crouching horror on the pedestal and Rakor Gribold suddenly

became synonymous with everything that was inhuman and evil. I dropped

the tool I was working with. A timid knocking sounded at the door. Sweating

with relief, I turned from the statue. Rakor Gribold yelled fiercely as

he saw the latch slip.

"Put

that tray down outside, you blundering idiot, and stay out! Stay out, I

say!"

The tray

clattered to the floor. Cursing softly to himself, Gribold crept across

the room. He jabbed the sharp broken end of his cane viciously through

the large keyhole. If Mason had been there, he would have been blinded.

I shuddered. This whole business was getting on my nerves.

Gribold

put the tray on an improvised table and grabbed a chicken leg. The meat

was gone in one gulp. Gribold tossed the bone to a far corner of the room.

There was a sharp squeal, a scurrying of feet. I saw beady, unblinking

eyes gather from every corner of the room to stand just outside the feeble

circle of light. Gribold talked to them, flung them bones and bits of meat.

It occurred to me that the rats had always been there, waiting for bones

and meat!

I forced

myself to eat something, lit a cigarette.

Gribold's

eyes blazed. With one bound he reached me, struck the cigarette from my

hand into the fire.

"You

fool! Would you take the chance of destroying the statue with a careless

cigarette tossed too near it?"

Then

he calmed himself, but with difficulty. I stared at the hideous, mouthing

face. The man was insane.

Gribold

was muttering apologies, placating me, but I determined to double my energy

and finish the statue's arm. Why was he so afraid of a cigarette when that

pit was always burning, filled with flames?

That

night at dinner it was the same thing again -- the horrible wolfing of

meat in one form or another. I felt my appetite dwindling away before the

carnivorous voracity of Rakor Gribold.

Mason

came in wit the wine on a tray. I noticed that the cockney was even more

haggard than he had been the night before. He was trembling so violently

that I wondered if he had seen a ghost.

He poured

my wine and moved around the table to serve Gribold. His trembling upset

the bottle and it rolled off the tray, striking the table. Its contents

poured over the Master of Gribold.

Gribold

jerked to his feet. He flung his chair spinning to the wall. His face was

a contorted replica of the statue in the dungeon. He seized the unfortunate

man by the scruff of his neck. One mighty arm held the petrified servant

dangling in mid-air. Gribold swung him gently back and forth. Mason's face

started to get purple. I arose, suddenly angry, and advanced toward my

host. Then Gribold flung Mason ten feet across the room to slam into the

door and roll out of sight into the pantry.

"Now

stay out, you incompetent fool. That was our last blunder."

Gribold

roared with laughter. The sound made me collapse suddenly into a nearby

chair. The man was the devil's twin. His laughter came straight from the

sulfurous depths of hell.

Sometime

after midnight I awoke. The old manor was vibrating with sound. It took

me a moment to come to my senses. Then I realized what I had heard. A man's

scream of mortal agony had set the echoes reverberating through the corridors.

Even now I could still faintly hear it rolling away through the vast halls

and rooms.

I grabbed

up my robe, paused to light a candle, and rushed down the stairs. The light

from my candle flickered and almost went out. I stopped, shielding it carefully

with my hand. The shadows on the ceiling and walls were hideous, threatening

ghouls reaching for the trail light that was my only guide.

The house

was silent, chill, like a huge galleon at the bottom of the sea. The same

chill, the same awful silence hung over the evil Manor.

Down

through the long corridor to the kitchen I ran, through the back pantry

to Mason's tiny room. It seemed as though time stood still. There was a

breathlessness, a suspensive waiting for the same noise to break the spell.

I called aloud.

"Mason!

Mason, are you all right?"

Mocking,

echoing voices mimicked me, flinging the words away into the darkness.

Mason's

room was empty, the floor ajar. Suddenly I thought of the dungeon. Mason

had mentioned the irresistible attraction it had for him. Could he

have gone down there tonight?

And then

came that same inexplicable sensation of eyes watching my every thought

-- the cold scrutiny of my brain by some hidden evil force. Somehow, the

thought of searching the corridors, peering into the dungeon for Mason,

seemed fearfully alluring.

I found

myself running through the kitchen, down the long hallway to the massive

oak door that led to the dungeons.

Dodging the dank pools an d

low hanging moss, I hurried through the corridor. There were hundreds of

bats beating wildly through the moss and roots near the beamed ceiling.

They dived a me, emitting eager shrilling noises. The candle attracted

them. It was all I could do to beat them off.

I passed the cell where the

bones hung, rounded a sharp turn. The door to the forbidden room was closed.

I tested it. It was locked. I felt relief sweeping over me. Mason hadn't

gone in.

But I had to look through the

keyhole . . .

The room was hazy, filled with

a luminous smoke. Faintly I saw a figure at the cauldron. It was stirring

the brew with mighty sweeps of the leg bone. First it was the witch. Then

it had four arms. Finally it was Gribold bending over the stream. I rubbed

my eyes. Why were all those impressions leaping at me? I looked again.

Steam, thick and fetid, poured

out of the cauldron. No figure bent over it. I tried to see more of the

room, the pedestal, the statue. My eye caught the glinting lights on the

floor. The rats were out again. Then I heard them. They were squealing,

fighting viciously over some dark mass on the floor near the fire-pit.

Suddenly, as though something

had deliberately extinguished it, my candle flame went out. The whir of

wings swept my head and face. The candle wick glowed briefly and died.

Fear swept through my veins.

I stumbled ot my feet, ran blindly forward. I crashed into the wall a the

sharp turn. It jarred me back to my senses. I slowed down, concentrating

on the corridors, the branching tunnels, any sort of landmark. I could

make it. It would just take a little time.

Waving my arms in front of

my face, I groped slowly along. The cobblestones were a help. The side

tunnels were all planked with wood. I could feel the difference if my feet

didn't freeze. I had lost a slipper in my blind flight. The slimy pools

of the corridor were unpleasant, but at least I knew that I was on the

right track.

Then I lost my balance and

crashed to the floor. I had stepped on a huge toad. I felt it squash through

my toes. I almost screamed as the gelatinous mess oozed over my foot.

I floundered forward, dragging

my foot over the cobblestones, trying to free it from the mucosity of the

entrails.

The swooping bats, the toad,

the darkness, all contributed to my hypnagogic state. I forgot the cobblestones

by which I had been guiding myself through the damned place. I ran, stumbling,

cursing, dashing my face and body against unresisting walls.

The pain of my cuts and bruises

finally slowed me down again. I groped against a wall, panting, hurt, cursing

the day that Mason had brought me the money and letter. It would take more

than two thousand to pay me for this. Welcome anger poured over me, replacing

my blind panic.

And then I felt it. The wall

was moving under my bare hands! I could feel it move where I had

slumped against it to rest. It crackled, rustled. The stench was nauseating.

My God, I had leaned against

the cockroach wall!

I flung myself forward, fell

into the arms of a thing that was huge, muscular beneath its baggy clothing.

Several arms seemed to grasp me. Rakor Gribold's voice cut into the nightmare

of my thoughts.

"Are you lost, Mr. Renton?"

He struck a match, lit a candle.

Then he guided me out of the cockroach tunnel, into the main corridor.

I was numb. I couldn't think. I could hardly move. Gribold helped me thorough

the long hallways, up the stairs to my room.

I flung myself on the bed,

too exhausted to care whether or not I had picked up any cockroaches, that

my foot was still slippery with toad slime. I fell into a deep sleep. My

last conscious thoughts were:

"What had Rakor Gribold been

doing in the dungeons? Could he see in the dark like any nocturnal creature?"

Next morning I awoke to find

myself stiff and sore. In the light of the new day, my reactions of the

night before seemed unexplainable. I had never had nerve trouble before,

had never experienced a powerful phobia like the one that had driven me

so near to madness the night before.

Mason's disappearance was not

mysterious at all, I reasoned. He had probably taken the night train out

of Gribold village. He was so anxious to go that he hadn't bothered about

the few possessions I had seen in his room I had rather liked Mason in

spite of his perpetual terror. I would miss him.

I would finish the work by

evening and leave the following morning.

I went immediately to the dungeon.

Gribold unlocked the door for me and disappeared. I didn't see him again

until that night at dinner.

Working steadily all morning,

I was grateful for once of the deep silence of the place. The work progressed

rapidly. I felt my old joy of accomplishment returning. Around noon, I

began to get a little hungry and wondered why Mason did not bring the tray.

Then I remembered that he had gone. So I worked on.

I was finally ready for the

finishing touches -- those little cuts, the adding of a wrinkle or tracing

a vein, perhaps the smoothing and defining of minor forms. Those are the

intangible factors that make art approach reality.

Before I began, I stood back

to look at the figure as a whole. How hideous it was, yet awe inspiring,

too! It seemed to be the embodiment of all the evil grotesqueness of this

world and the next.

It crouched as though about

to spring. Two of the muscular arms and hands were curled about the base

of the pedestal. The other two were curled about the base of the pedestal.

The other two were curved forward, bent at the elbow, the fingers clenched

as though to strangle the air between. The squat head was thrust forward

with quivering intentness. The eyes seemed to glitter, the mouth to drool.

For some reason I thought of

Mason, poor Mason. I shook myself free of the spell of the thing. Why had

I said poor Mason? He was probably miles from here by now, looking forward

to joining the Queen's Navy again.

I forced myself to laugh, swung

my arms about, relaxing the tired and sore muscles. Then I started to work

again.

The rats seemed to be quieter

than usual. I didn't hear them scratching and squealing as they had done

the previous day.

Only once during the day did

my nerves go back on me again. I had been working on the closed hand, rounding

the knuckles. I was using a sharp pointed instrument of fine steel that

I had invented for the numerous bits of detail in the final stage of reconstruction.

I had struck the tool in the forearm of the statue to have it handy.

Suddenly I heard a faint clawing

noise at the door. I turned to see what it was. A great rat was dragging

a bone across the floor. I threw a piece of the plastic stuff at it. The

rat scurried away into the darkness of the room.

When I turned back and reached

for my tool, it was clenched in the hand I had been working on! I was sure

I had left it stuck in the forearm. But my nerves were still shaky from

the night before. I must have experienced a brief period of amnesia. I

had to get out of this place before I really did break . . . .

Two hours later, I was through.

At least my work was as near complete as any artist will ever admit. I

gathered up my tools, gave the statue a farewell glare and went up to my

own room.

Not having

eaten all day, I was as ravenous as Gribold that night at dinner. I was

aware that he was watching me constantly. When I told him the statue was

done, he seemed in high spirits, grinning and chuckling to himself. The

meat juices trickled through his beard, dripped off his chin in a greasy

stream.

He began

questioning me about the meat. Did I like it? Was it tender enough for

me? He seemed unusually concerned and I felt myself getting unaccountably

angry at him. I worried over the meat, pulling it here and there in the

gravy. It seemed more fibrous than usual, but hunger is a great factor

for overcoming the aversion to slightly unpalatable food.

I had

almost cleared my plate. There remained only a chunk of fat with a small

piece of meat stuck to it. I dug my fork into the fat. It fell apart.

Then

I saw it, floating half submerged under the fat in the gravy. I poked my

fork at it tentatively. Here again my imagination flooded my reason with

a horrible thought. The peristaltic muscles of my stomach began to reverse

their digestive action.

I flung

my chair back from the able and ran out of the dining hall.

Staggering

up to my quarters, I retched miserably, fell on my bed, completely unnerved.

The thing

that my fancy had pictured floating, half submerged in my gravy, was a

purple tattoo mark. The mark of the Queen's Navy had once been on Mason's

forearm!

The Authors

John

Coleman and Jane Ralston Burroughs

.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()