It occurred to me to wonder why there are still dinosaurs in Pellucidar,

and how they coexist with other species. I mean, what's up

with that? There are lots of places on Earth where the habitat is probably

similar to what the dinos had in their day. No sign of them (at least,

not in any significant numbers).

It occurred to me to wonder why there are still dinosaurs in Pellucidar,

and how they coexist with other species. I mean, what's up

with that? There are lots of places on Earth where the habitat is probably

similar to what the dinos had in their day. No sign of them (at least,

not in any significant numbers).

So, why did they vanish topside and how did they hang

on down below? Same goes for all sorts of other extinct critters.

Well, thinking things through logically, we've witnessed

several mass extinctions topside, and as best we can figure, mass extinctions

seem to derive from three major causes:

1) Nasty ass stellar events. Either comets or asteroids

hitting and going boom, or supernova putting out enough high intensity

radiation to sterilize entire species and fry the ozone layer, precipitating

ecological and climactic collapse.

2) Climactic and geological changes. An ice age

comes along, that's it boys, we're frosted. Or alternatively, continents

get jammed together, continents get pulled apart, the species plays their

cards and winds up busted. Horses and elephants colonized North America,

but eventually became extinct there. Meanwhile, Camels evolved

in North America, failed here, but did fine in Asia and Africa.

On an Island continent like Australia, a species had no where to escape

too if things were not working out, and thus would disappear permanently.

Essentially, local conditions could bring about local extinction, and if

a species was not sufficiently widespread, local extinction could mean

extinction period.

3) Other species invading and disrupting habitats...

As we've seen with the obliteration of the South American megafauna by

the invasion of North American megafauna. Or as you see with us... we've

been bad news for just about every other species we ever met, ask the woolly

mammoth, the bison, the dodo, etc.

Well, thing with Pellucidar is, down on the underside,

there's no asteroid impacts and no super-nova fry jobs. There

is a nice external thousand mile thick planetary shell that protects the

Pellucidareans from impacts and radiation. So we can

pretty much not worry about that. That's a pretty big load

off everyone's mind.

Also, given Pellucidar has a stable constant sun, no nighttimes,

no seasons etc., we can rule out rapid climatic shifts. There

will be no ice ages, no rainy eras, no dry spells, no nothing.

It's broadly stable weather and climate for the underworld.

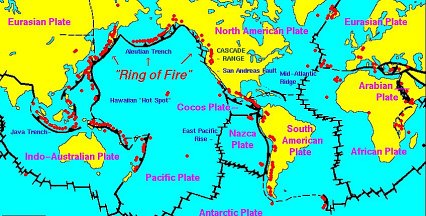

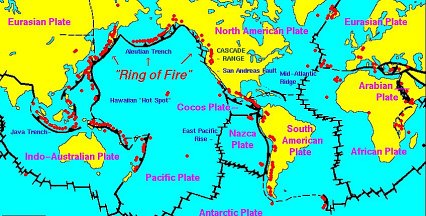

Geologically? Well, I've been thinking some more about

this, and I believe we have to recognize that Pellucidar's plate tectonics

are organized a little differently than the topside. Pellucidar probably

has a lot more tectonic plates, smaller tectonic plates, and more active

plates than topside.

So, although they look like continents, and Pellucidar’s

ratio of land to sea may actually be much higher than topside, structurally,

Pellucidar's lands are actually a large number of smaller plates or 'islands'

wedged up together, and often quite difficult to pass from one to

the other. But because of the speed of Pellucidar’s tectonics,

the plates are constantly mixing and merging, thus while barriers are common,

gateways are also geologically frequent. This has a couple of effects.

The jamming and mixing of multiple plates means that over

time, a species will have opportunities to spread great distances.

The Australian fauna were trapped in Australia. North American

or Asian animals could emigrate and therefore their species could avoid

extinction by establishing populations in other continents in more benign

conditions.

In Pellucidar, there are very few long term traps, and

a lot of opportunities for species, over that long term, to emigrate and

establish populations in different areas. The more widespread

they become, the more difficult extinction becomes.

But the continuing movement of the small plates against

each other creates an endless succession of Islands which are temporarily

protected from each other (temporarily, in this case may mean millions

of years) . This makes the 'introduction of new species to

wipe out old ones' far more problematic. New species just have

a harder time getting into vulnerable “Island” populations.

Pellucidar is more prone to big canyons and sharp

jagged impassible mountain ranges, which continually form barriers to life

and species movement... although these barriers probably rise and fall

over millions of years.

When the flora and fauna of two 'islands' meet, one can wipe out the other,

as in South America and North America. However, lots of ‘islands’

also means that there's more chance of a 'reserve' or populations surviving.

The South American fauna, unlike horses and camels, didn't have a biological

‘bolt hole’ that their species could retreat too, if they failed in their

home areas. In Pellucidar, most species may have all sorts

of bolt holes and safety refuges, from which they can recolonize local

areas where they went extinct.

When the flora and fauna of two 'islands' meet, one can wipe out the other,

as in South America and North America. However, lots of ‘islands’

also means that there's more chance of a 'reserve' or populations surviving.

The South American fauna, unlike horses and camels, didn't have a biological

‘bolt hole’ that their species could retreat too, if they failed in their

home areas. In Pellucidar, most species may have all sorts

of bolt holes and safety refuges, from which they can recolonize local

areas where they went extinct.

And of course, the mechanics are that large populations

colonize smaller populations. Large populations have more opportunities

for mutations, they have access to a wider range of environments and thus

tend to be more robust and competitive. Thus, animals from

the ‘Old World’ of Eurasia/Africa/North America tended to be more competitive

than the comparatively small ‘island’ of South America.

On the other side of the coin, tendency seems

to be that on islands, even Island continents, the rate of evolutionary

development seems slower. Smaller ecologies seem to be more

stable. Within an ‘island’ there is less room for a population, and

within a small population, there's less mutation, and less competition,

and less diversity of environments, so much more stability. Of course,

given the small population, a mutation can establish much more readily,

so that new species can and will emerge on islands, and even emerge more

quickly. But they will often be more vulnerable to outside pressure.

If Pellucidar is a sequence of small populations, then

there may not be the inbuilt advantages or evolutionary propulsion that

allows large supercontinents successfully colonize islands and island continents

on the topside.

It's likely Pellucidar has still seen species extinction,

but its far slower, on a more reduced rate than ours. And its likely that

pressured species are more often able to find a bolt hole or refuge.

Evolution probably takes place, as does competition.

I can't really say that for sure, but there are signs of it. The Triceratops,

for instance, are a lot bigger and meaner. There are stegosaurs that appear

to have managed a primitive form of gliding. Certainly there's nothing

like the Mahars, or the Serpent men in the topside fossil record, so they're

either undiscovered species, or perhaps indigenous Pellucidar creatures.

Under the circumstances, it seems plausible to

me that some degree of evolutionary pressure is going on down in Pellucidar,

to produce occasional new species, and to produce fairly radical changes

in old species.

Which may allow us to infer that there is evolutionary

pressure or competition. But if that pressure or competition has enough

safety hatches and soft landing areas, then normally non-competitive or

less competitive species may have opportunities to toughen up to meet the

challenges. Or to find their way into stable secure niches where other

species can't bother them easily.

However, without the savage mechanism of extinction, it

is difficult for new species to establish themselves through evolution.

One cannot grow into ecological niches, they are already occupied.

One must be pre-grown in order to compete. Thus, its likely

that most species in Pellucidar have not evolved there, but probably made

their way in from the outer world.

Most new species come from the topside through vortices,

which in themselves act as temporary barriers. The very creation

of the vortex on top side creates geographical barriers for the spread

of underside critters. It's likely that there are similar (although different)

geographic effects on the undersides of the vortices that stall or slow

the spread of new species... allowing the existing species opportunities

to adapt to cope with the new interlopers.

The bottom line with Pellucidar then, is that the various

species that move in wind up finding homes here and there, and once they've

moved in, they get pretty hard to dislodge. On the small 'island' biomes,

natural selection dulls the edges of the smart and fierce, and gives the

slower and dumber

opportunities to smarten and fiercen up.

Thus, it would appear that the topside's geology, with

its massive supercontinents, vulnerable island continents, radical changes

of climate, seems almost designed to create extinctions. Thus,

the topside is the biological laboratory of Darwin, the land of survival

of the fittest, the continuing source of speciation.

Meanwhile, Pellucidar, because of its geology and environment

seems to act in precisely the opposite way. It's difficult

for a species to become extinct in Pellucidar, the opportunities for both

refuge, proliferation and adaptation seem to weight against extinction.

Thus, Pellucidar has become Earth's biological storehouse of races and

species now long gone from the top side.

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()