Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute Site Since 1996 ~ Over 15,000 Webpages in Archive Presents Volume 1494 UNRAVELLING AMTOR

|

Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute Site Since 1996 ~ Over 15,000 Webpages in Archive Presents Volume 1494 UNRAVELLING AMTOR

|

CONTENTS Introduction Wrong Way Carson! Maps of Amtor Making the Most of the Map Attempts at a Corrected Map Carson's Verifiable Venus Life on Venus Avenue Burroughs Venus Looking for Matches on the Planet of Love Assuming Venus Equals Amtor, What Conclusions? Getting to Amtor

Introduction This is a sequel to rewarding and interesting attempts to match current Mars to Burroughs Barsoom. Unfortunately, most sequels tend to be a step down from the original. The best ideas have been used, the sequel must either go through paces originally set, with less originality or accomplishment, or it must take chances by departing from the original while still tied to it. In either case, the results are often unsatisfying. True to form, the effort to match Amtor to Venus is apt to be considerably less rewarding and a lot more frustrating, to both reader and cartographer. But on the other hand, if you're reading this, then you've probably read many of my other examinations of Burroughs universe, and you're pretty much along for the ride, aren't you? Fasten your seat belts. The differences between the two situations are profound. With Barsoom, John Carter and his kin and allies crossed from one end of the planet to the other, charting planet spanning rivers, immense marshes, now covered hills, visiting each pole as well as mighty cities, dead sea bottoms and lost cities. Through the course of the Martian series, Barsoom was thoroughly mapped, with both political and geographic features revealed in detail. There was plenty of room left, of course, but the shape of the planet was well established. This gave us a wealth of detailed information on the geographical and geological features which we could then apply to Mars and find a greater degree of correspondence than we had any right to expect. Venus.... Well, Venus is kind of a mess. Where to begin? Well, let's start with the reliability of our narrator: Carson Napier.

Wrong Way Carson! A man who took off in a spaceship for Mars.... And wound up on Venus? That's not encouraging. How did that happen? Apparently, he forgot about the Moon. That's even less encouraging. Shall we consider Carson's history on Venus?

Speaking charitably, Carson is either spectacularly unlucky, or he has a very poor sense of direction, or he may actually be handicapped, perhaps dyslexic. This is the man we are relying upon for our geographical knowledge of Amtor. Frankly, we should be astonished that he can distinguish Mountains from sand dunes. Right at the start, we've got big problems. When investigating Matching Mars, I noted that John Carter was a slightly unreliable narrator as his sense of direction was occasionally not the best. He or his allies would go astray from time to time. Accordingly, given Barsoomians propensity for getting lost, a certain margin of error had to creep into their estimates of geographical locations. But Carson? My god, I should have quit when I was ahead. This is a man who could get lost on the way to the refrigerator. If Barsoomians' sense of direction entitles us to a certain margin of error, what are we to make of this guy?

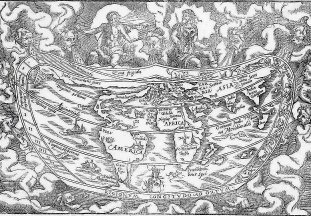

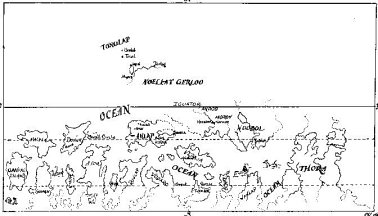

Maps of Amtor Ah well. Despite the inherent unreliability of our narrator on matters of geography, we still have the residents of Amtor, don't we? They know their planet, don't they? They can find their way about and make decent maps, can't they? Perhaps not. Here is the archetypal map of Amtor's southern hemisphere, drawn according to the Amtorian cartography, provided to Carson and through him transmitted to Burroughs and thence to us: We have a problem here. The Amtorians, Carson discovers, are even more incompetent than he is. The Amtorians of the southern hemisphere, as just one example, have not the slightest clue that a northern hemisphere even exists. In fact, they refuse to believe in any such place. That in itself, is not a good sign. They believe that the southern hemisphere is a huge saucer with an upturned rim sitting upon a sea of molten metal and rock. Flat earthers are not known for their command of geography, and the Venerians go it one further by attributing a convex rather than concave structure to Earth. In short, their maps are inherently distorted by getting the curvature inside out, assuming that they are sophisticated enough to adjust for curvature. It's not clear to us that they are. Whether they've flattened their curvature or actually inverted it, we can take it for granted that they've basically screwed up this fine detail. It goes on. The Amtorian sailors, due to the poor quality of their maps and cartography, hug the coastlines as their only hope of avoiding getting lost. There is no navigational instrument more accurate than a compass. Reckoning by the sky is impossible, considering the eternal cloud cover. The thick cloud cover and the ionosphere make effective radio or radar impossible. All of this seems to suggest a fairly primitive mapmaking tradition. Even were they not so horrifically backwards, Amtorian maps would probably be highly inaccurate, perhaps on a par with sixteenth century maps. In those days, maps were developed from sailors reports and measurements, from multiple inconsistent reports where scale and time varied immensely. Distortions accumulated. Obviously, you could not get a shape of the world, or even of North and South America from a single seafarers charts and notes. Instead, a seafarer would make a map of a relatively small area that he explored. Cartographers made large maps by assembling these small maps from multiple sources, into larger ones, guessing at scales, relationships and joinings by constantly referring to different sets of seafarers charts, notes, observations. It was quite easy for every sort of error to creep into these maps. One seafarer might pass by a region and miss a river, another would come at the region from another perspective and spot a river. One river might be mistaken for another river. In joining maps, a mapmaker might look at two descriptions of the same coastline, decide that they obviously must represent different areas, and depict the same area twice. The mathematics that allowed the world to be divided into latitude and longitude, and the sophisticated systems of cartography that both recognized that the world was round, that the earth was curved, and allowed for that curvature to be adjusted for on a flat map simply did not exist. Thus, for all these reasons European maps appear distorted and childish to modern eyes. As we see here with this early map of the new world. Note that while North America is somewhat recognizable, its also horribly distorted, the upper part is appallingly broad, Florida is a mere stub and not the graceful extension we know, Cuba and Hispanolia are actually almost touching, the gulf of Mexico is gnarled like a rotten orange peel and South America is entirely shapeless. In many ways, this 1587 Map is pretty good. People

have been mapping the new world world and sailing the

Here's another example:

http://historymedren.about.com/gi/dynamic/offsite.htm?site=http://scarlett.libs.uga.edu/darchive/hargrett/maps/neworld.html Observe the lack of scale and proportion in this earlier map from 1544, over fifty years after Columbus, which manages to identify most of the world but has only rough estimates of contours." Notice how the shape of Africa deforms into a railroad spike, while East Asia is a distorted mess? The sliver of the coast of South America is reasonable, but on the other hand, small Islands are depicted completely outsize, and Antarctica seems to have several large Madagascar scaled islands which do not actually exist. Now, I'm not slagging 16th century maps, and in particular, I'm not slagging these maps. The maps I've shown you were state of the art maps by the most brilliant cartographers of the day, these were the cutting edge maps, well ahead of their rivals. The 16th century was full of a great many crummier maps. We must remember that the 16th century was a time of unparalleled exploration in which entire new continents and oceans were discovered and Europeans sailors on tiny ships wandered the seas with few of the advantages that we have now. With all their handicaps, it is astonishing that the maps they made were as good as they were. Rather, they are presented to show the practical problems and errors that come about trying to construct coherent maps, even with a reasonable degree of sophistication. Of course, I would argue that the 16th century mapmakers were well ahead of their Amtorian cousins. For one thing, they hadn't bunged up the shape of the Earth completely. For another, the 16th century sailors had better instruments, the advantage of reckoning by the sun and stars, and were by all accounts, bolder explorers than the Amtorians. So, in all likelihood, the 16th century maps of Earth are probably better than the Amtorians maps of their own world. Or to put it another way, the Amtorians had a few handicaps built into their cartography. Even if the Amtorians had gotten things right, their maps would probably still be profoundly crude. The distances and relations between islands and locations, and therefore the shapes of geography, are almost certainly distorted by local variations in speeds of wind and current, which make journeys faster or slower and leave measurements shorter or longer. Moreover, it is clear that the Amtorian mapmakers, cartographical mathematics are all but useless. The mapmaking information must come from seafarers endlessly feeling their way around by dead reckoning without even instruments or stars to guide them. Thus, the charts and maps of these seafarers must be appallingly crude and inaccurate, even by the standards of early Europe. On top of that, it is very clear that the Amtorians, at least at this point in their history, are not terribly good explorers. Otherwise, Vepaja could not be so profoundly mistaken about conditions on Strabol or Karbol. With respect to Karbol, they genuinely believe that the centre (equator) is uninhabitable, and so do not go there. With respect to approaches to both Strabol and Karbol, they report only strange beasts and stranger men, similar to the ‘here be dragons’ approach of European mapmakers. Of course, this is as nothing compared to their principle belief. That geography is reversed and that the center of their world is a hot flaming core area, which is actually the equator surrounding them. Meanwhile the rim of the saucer shaped world is a cold icy place.... Actually the pole. Of course, even to Carson this seems lunatic. Carson points out that measurements of distances must surely suggest that there is something wrong with this theory. After all, the measurements of distances around what they believe are the outer rims are very short, measurements around the hot core are very long. And in fact, the Amtorians had done surveys which showed endless apparent discrepancies between the values given in their maps and those encountered by actually going out and measuring things. Unfortunately, this did not dislodge their theory. Instead, they resolved the contradictions by multiplying the numbers by the square root of minus one. As Carson said: “There is no use arguing with a man who can multiply anything by the square root of minus one.” Consider, if you will, how geographically illiterate a nation must be, if a man like Carson turns his face away in disgust. All of which, we argue, seems to go substantially towards undermining the practical value or reliability of local Amtor maps. At best, it is likely roughly comparable in quality to the maps produced by 16th century Europe, whose style it resembles. But the geographical inversion makes it all bizarrely wrong headed. This is particularly relevant, since our best key to Amtorian geography is a native map which even Carson insists is absurd and useless. And of this map, we must ask hard questions. How was this map transmitted to Earth? Was it genuinely a native Amtorian map, or was it Carson's own reproduction and transmission of a map that he had seen. It seems likely, given his sense of direction, that Carson is dyslexic, so the map may or may not be reversed. Moreover, given Carson's own geographic skills, we can expect any map transmitted through him will be certain to have accumulated a few errors. So, let's recap: We have primitive mapmaking based on the results and measurements of timid sailors without adequate tools or navigational aids, incorporated into a horrifically wrongheaded cartographical view of the world, resulting in badly flawed maps which are then reproduced in Carson's mind, adding new errors, and possibly reversed through dyslexia. It would be a cosmic level of charity to say that we might occasionally be justified in taking Burroughs Venus map with a certain grain of salt. At best, it's a starting point.

Making the Most of the Map So, given that it's a starting point of inverted scale, possibly reversed perspective, and endless inbuilt errors all the way through, what can we say. Remember that when 16th Century European cartographers made maps, they had no way of accommodating or adjusting for curvature. By that time, they knew it was there, but the grid system of latitudes and longitudes was not established. Hence they tended to try to have realistic surface or geographical features, but over large scales, these features invariably distorted. The distances stopped making sense. However, for relatively compact objects like islands or peninsulas, it was easier to avoid distortion. The shapes of islands could be accurately mapped out by seafarers. Thus, small places like Norway, England, Haiti and Florida show up relatively well on early European maps, while Europe and North America turn out to be dog's breakfasts. Early European cartographers also did quite well with places that they knew well. There were a lot of seafarers from and around England, Spain and Portugal, which meant that there were large databases of charts and small maps, and these charts and small maps circulated and were continually tested and refined. So, first of all, its likely that the map gives a relatively accurate portrait of Vepaja, in much the way that European maps gave more relatively accurate portraits of England and Spain than they did of North America. We can assume that Vepaja probably is pretty close to how it is depicted on the map. Beyond that, we can assume that the closest islands to Vepaja are probably quite well explored and well known. Their shapes are probably fairly close as well. Thus, the profiles for Trambol and Zando north of Vepaja, and Anlap south of Vepaja are probably basically accurate. We note that the northern half of the Trambol coastline seems speculative, apparently mapped out, but not detailed. As well, the southern half of Anlap also appears undefined to the point where it is not clear to us if Anlap is a stand alone Island or a peninsula of a larger continent.. This may well be evidence of the timidity of Vepajan sailors. If this is the case, then the farther we go from Vepaja, the dicier our judgments become. On the other side of the map from Vepaja, in the temperate zone, there are a series of large islands, Sanfal, Malpi, Donum, Movis and Nok. Sanfal, Malpi and Donum form a line leading to a large peninsula (or Island) called Ator. Donum and Movis are side by side, facing Ator, with Movis being off the aforementioned line. Nok is on the other side of Ator. Overall, with this archipelago, we can say that the Islands in question reasonably exist, and have the geographical relationships between them that the Vepajans describe. Less confidently, I would be prepared to say that these Islands are in the shapes described in the map. There may be errors in size and orientation of these islands. I've seen an early map of the Caribbean from Columbus’ era that somehow managed to have Jamaica turned completely on its side. There is one small but notable discrepancy between the Sanfal archipelago from the Vepaja archipelago. If you look at the map, we see that Vepaja is surrounded by small satellite islands. These are too be expected, since the geological processes that would produce huge Madagascar sized islands would probably produce smaller secondary islands. But the Sanfal group shows no smaller secondary islands. Perhaps they do not exist. Or perhaps this area is less well known to the Vepajan cartographers and so secondary or satellite islands have been omitted or lumped in with the big ones. I'm guessing here. We note that on Earth, giant Islands tend to either be isolated, as in New Zealand, Newfoundland, Madagascar. Or they tend to be parts of closely grouped archipelagos. The Philippines, Indonesia, the Canadian Arctic or the West Indies. It's dangerous to simply extrapolate Earth conditions to other worlds. But there appear to be two broad groups of large islands in the Southern Hemisphere, and so it is tempting to suppose that they are both archipelago complexes. If indeed they are archipelago complexes, then it is likely that they are relatively closer to each other, in the context of the overall hemisphere, than the map might suggest. But this is just a guess. The discussion of islands is fairly important, since in the attempt to rectify the map, we would normally see minimal distortion in the Trabol area, but a real tendency to distortions in both Karbol and Strabol. We should be cautious in that the renditions of the Islands themselves are probably fairly accurate and should not be unduly distorted. Of course, where we get into trouble is in Karbol, which is actually the central polar region distorted into an equator. There appears to be a continental or pseudo-continental mass at the pole which is represented by a series of peninsulas extending outwards. One of the problems here is that we have no way of knowing, on this map, where the actual pole is. We are hampered by the mapmakers timidity. We know that the map defines a frozen and inhospitable equator, but the progressive lack of detail of the map as we approach this equator tells us that the level of exploration is sadly lacking. So, does the Equator represent the exact spot of the pole? Or does the Equator represent a circular distance ten miles from the pole? Fifty miles? One hundred? Five Hundred? Without knowing this, it becomes difficult, even impossible, to gage the size of the south pole continent or its true shape. At best, we can only relate a series of peninsulas which appear to radiate out of the South Pole, including Ator, Rovlar, Vodaro, Vaxlap and Sombau. These features almost certainly represent the coastlines of the South Polar land mass or perhaps of separate land masses, but may not be true peninsulas but merely unexceptional coastlines, distortions and artifacts of the mapmaking process. It's entirely possible that some of these peninsulas may not even exist in any geographical sense, but are merely ‘doubled’ sections of coastline stapled together to accommodate uncertainty or fix a glitch (early Earth cartographers were not above doing this). Where we get into really big trouble though, is with the real equator, depicted here as the centre of the map. By stretching a polar region into an equatorial circle, geography is brutally distorted. But on the other hand, there is plenty of room opened up. That poses some problems, but it does allow for depictions of geographical features. By closing the equatorial region into a circular point, however, the distortion increases geometrically. The map deals with this by having almost no information, or contradictory information as to the central point (equator). Ocean? No ocean? Land? The map doesn't know, can't say and won't say. Again, with the pole, we have the problem that we have no clear idea of what the relationship of strabol and the centre point of the map is to the true equator. It's possible that it falls several hundred miles short of the equator, or stretches several hundred miles past the equator into the northern hemisphere. What we have is unknown and unknowable territory. Despite this, there is useable information here. It is clear that there is an Continent straddling a substantial length of the equator, at least forty per cent, and perhaps as much as sixty per cent of the arc of the Equator. It appears that the area described as Anlap may actually be a part of this continent. The equatorial interior of the continent is largely undescribed. Coastal areas, particularly those nearest Vepaja are described well, and the countryside is even divided up between Thora, Kapdor, Morov, Kormor, Havatoo and Andoo. All indications are that the continent extends into the northern hemisphere, and that neither its interior nor much of its coastline has been mapped. The overall shape of the continent is unknown and unknowable from this map. There appears to be a ‘leg’ of this continent that extends down from the equator, into the equatorial region and towards the pole. Whether it actually merges with the polar continental masses is not clear, thanks to the timidity of the Vepajan explorers. Note that both temperate coastlines of the continental leg appear to be well described, and internal features such as rivers are noted. The coastlines may be somewhat accurate, but the overall shape of the leg is probably grossly distorted It also appears that the area of the equator around the Sanfal, Malfi Donum archipelago is not bounded by the continental mass, but may be relatively open waters. So, what is the bottom line? We've got a pretty

clear picture of two major archipelagos of giant Islands on the scale Indonesia

or the Canadian arctic, probably relatively accurate in outline and relationship

to each other, probably grouped more closely than we might think at first.

And we've got an apparent southern polar continent or continents, which may or may not join with the leg. It's possible that the equator and southern polar body are all a single connected land mass. Or they may divide into distinct land masses.

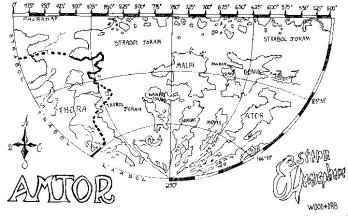

Attempts at a Corrected Map I should take a moment out, at this point, to acknowledge the work of previous Unreal Archeologists who strove to unravel the confusion of Amtor's geography and work backwards to a corrected map. In particular I offer congratulations of J.G. Huckenpohler’s cylindrical projections, to be found here:

http://erbatlas.virtualave.net/amtor7.shtml I emphasize Huckenpohler particularly because his cylindrical project is probably the best available yardstick for comparing Amtor with topographies of Venus. I'd like to offer a congratulations to Dale Broadhurst and Bruce Wood's corrected south hemispheric maps, to be found here:

http://erbatlas.virtualave.net/amtor2.shtml And here:

http://erbatlas.virtualave.net/amtor1.shtml With a quite interesting explanation of the process and methodology behind the development of the map here:

http://erbatlas.virtualave.net/amtext.shtml The only real issue I have with Broadhurst and Wood is their need to insert an equatorial archipelago, which may or may not exist. There is no evidence for such, but on the other hand, they make a case for its necessity. Finally, there quite interesting maps by Frank J. Brueckel and Laurence G. Dunn.

Unfortunately, in my view, these maps as well suffer from perfectly reasonable errors. The creators have failed to take into account the necessarily primitive nature of Venusian cartography, and have treated their Amtorian source map as equivalent to a modern post-18th century terrestrial map. In this, they may well be correct. However, I would suggest a careful examination of the processes that lead to these maps would suggest a rather more primitive work. If this is the case, then the shapes of some of the islands and features depicted in the map are probably distorted, particularly the wedge shaped island and peninsular masses around the pole. Essentially, in trying to unravel the fundamental error of the Amtor map, they may have captured other hidden errors in the structure of that map, and even introduced new errors by distorting structures that the Amtorians might have gotten right (such as the shape of Islands like Vepaja or Trambol). Of course, the whole Venerian cartographic system is such a mess, that its hard to tell where and how they go wrong or right. The adaptations by fellows like Huckenpohlar, while brilliant, must be taken with a grain of salt. We should allow some room to maneuver.

Carson's Verifiable Venus What can we say definitively about Amtor's geography based on Carson's own direct experiences? Well, let's start with the basics. The southern hemisphere is divided into three regions: Karbol, the polar area, Carson discovers, is a cold country where people wear fur; Trabol, the warm country or temperate region, and Strabol, he is told is the hot country or equatorial region. Within these temperate region is Vepaja, which appears to be a large, Madagascar or New Zealand sized Island, maintaining an egalitarian society and cities within the boughs of five thousand foot trees. Carson, on Vepaja, is told that formerly, the Vepajans ruled “a broad empire that embraced a thousand islands and stretched from Karbol to Strabol; it included broad land masses and great oceans.” What does this tell us? The Vepajans first refer to a ‘a thousand islands’ suggesting that these islands constitute a substantial portion of lands, or at least, of civilized lands. Second, there is a reference to ‘broad land masses’ in the plural, meaning that the southern hemisphere sports at least two or more continental sized lands. If there was only one continent, it would be referred to in the singular. This may indicate that the Equatorial continent or Polar Continent are not in fact single masses, but may represent discrete bodies conflated on the map. In Pirates of Venus, Carson starts off on Vepaja, a Madagascar or New Zealand sized Island large enough to sport 5000 trees, cities in those trees, and fairly big and ferocious fauna like the Basto. Leaving the island, he has run ins with Thorists who appear to dominate the nearby continent and rule at least a portion of Vepaja's old Empire. Washed ashre in Lost on Venus, Carson makes his way on this unnamed Equatorial continent through countries called Kapdor and Nabool that borders on strabol and thus would probably gird at least part of the equator. On this continent, he observes flat tablelands cut by rivers. There are vast plains, forests, and old growth rain forests. Travelling from Kapdor, through Nabool, he passes through a section of wild land, descending into an immense river valley, eventually coming to Morov. Morov is largely unoccupied ruled by Skor from a capital city of Kormor, and appears to be directly between the Thorists and Havatoo. One thing quite notable about Carson's journey through this continent, is that he seldom encounters cities or habitation. Mostly, it is empty country occupied by Nobargan, monkey-like Pygmies, Zandars and various species of wildlife. This reinforces the suggestion that most of the civilized population is on the islands, and that the continent, and perhaps the other continent(s) are relatively unpopulated. Carson makes his way along until he encounters the mad scientist Skor who tells him that he is in Strabol, the hot country. Skor notes that it is hot during a portion of the year but not unbearable. Of course, Carson being the big goof that he is, leaps immediately to the conclusion that he is now in the northern hemisphere. However, according to the map supplied through Burroughs, Kormor, Havatoo, Morva and Andoo are all firmly within the southern Hemisphere. Once again, Napier strikes out! The most significant thing about Skor's comment is that it is only hot during a portion of the year... Which means that there are seasons and axial tilt to Venus. They encounter a girl from a place called Andoo, who comes from a mountainous foothill country with rapids and streams. She has no deep experience of swimming or diving, so we can assume that Andoo is in foothills country, without ocean or even large lakes or ponds. This in turn suggests a major mountain range even further into the interior, a fact confirmed later in Escape On Venus. From Morva, Carson flees, blindly stumbling along, and winds up eventually in Havatoo, a city state located not too far from Morva's capital. Carson settles in there for a while, returns to Morva to rescue Duare, and eventually has to flee Havatoo. Leaving Havatoo, Carson follows the ‘river of death’ (Gerlat

Kum Rove) to the sea. Crossing the sea, they eventually

come to the shorelines of Vepaja, but not wishing to go there, they continue

on.

Flying westward (eastward?) until they come to the land of Anlap, and the country named Korva, situated within. Most of Carson's adventures in Carson of Venus take place within Korva, in and around the city of Sanara. Duare returns to Vepaja with his flying machine, and eventually, he returns there to rescue her. The book ends with the two of them flying back to Korva. Northern geography is far more speculative than Southern Geography. Carson has no maps for reference, and once again, in Escape On Venus, he gets himself lost fleeing the fierce rays of the sun breaking through the clouds. No small thing, when the sun penetrates both cloud layers on Venus, the seas boil, forests are incinerated and a veritable hurricane forms instantly. But we do learn a few things from Carson's journey, his descriptions of countryside, and the Amtorians who supply him with information. His first stop is at the city of the Myposans. A city that lies at the shores of a great freshwater lake that Carson calls “Lake of Japal” for another city on its shores. The Lake is about about five hundred miles in length, which stretches nearly to the sea, but we have little information about its shape. The city of Mypos is about ten miles from the sea, so it is situated right on the northern rim of the lake. There is apparently a single channel in which the tides move sea water and lake water back and forth. And there is a great northern sea, with many countries along its coasts, suggesting that it is of substantial size, Carson later describes it as enormous. Interestingly, the northern Amtorians have the same language and writing as the southern Amtorians, though their tongue is beginning to diverge. Carson notes differences in customs, and a lower level of technology with boats powered by banks of oars. The Northern Amtorians believe that the world is flat, but have not compounded this foolishness by getting the poles and the equator mixed up. On the other side of the lake, the southern or inland end, is the city of Japal. About a hundred miles inland from Japal is a mountain range and behind it, the land of the Brokol. Geyond that, Carson writes, “We passed over some wonderful game country and several mountain ranges, until we finally came to the Timal country, a high plateau surrounded by jagged peaks -- a most inaccessible country and one easily defended against invasion.” So, he's apparently reached a mountain district. Attempting to return home, Carson seems to skirt the continent, flying out over the endless sea. But his sense of direction is true to him, and he winds up in the City of Voo-Ad, where he meets Ero Shan, who tells him that he too has flown from Havatoo across a sea to this land. The country of Voo-Ad is therefore, on a separate continent, which turns out to be Anlap. Anlap is clearly separated by a large expanse of sea from the Equatorial continent on its east side, but it is not clear what, if any, separation exists on the west side. Unfortunately, they're on the north side of Anlap, and Korva is on the south. Although they have encounters only plant men and nobargans in the northern part of Anlap, the Voo-ad museum has many male humans as exhibits, mostly warriors, but no females. This implies that the northern part is sparsely populated with humans. Carson offers a little more geographical information. In the interior of this land mass is a mountain range which he flies around, but then, he is shot down over an immense well watered plain, and finds a sort of permanent four cornered war going on between four cities. He continues to make his way south, with a few diversions, until he reaches the second Mountain range. It is inhabited by the Cloud men who turn out to be surprisingly friendly. Working his way through the Mountain range, he comes within sight of familiar landmarks, suggesting the territory of Korva, and he is now back home. Back in Korva, he eventually builds new airplanes and gets into trouble again. The Wizard of Venus features Carson getting lost once again, this time winding up on the Island of Donuk, one of the large Islands of the Sanfal range. Donuk is described as ten thousand miles from the Anlap continent or subcontinent, and due west from Sanara, the capital city of Korvam. Although this being Carson, I wouldn't bet my last dollar on those locations. For one thing, internal evidence seems to contradict Carson, he's only lost for several hours this time. When he wound up in the Northern Hemisphere, he flew lost for the better part of a day, his passage accelerated by a sun storm. Based on this, Donuk is probably closer than Carson describes.

Life on Venus Avenue The Venus of Burroughs is quite different from the world that we know. His Venus has oceans, life a breathable atmosphere and reasonable climate. Our Venus is a hellish hothouse, with air pressure equivalent to the ocean at a kilometers depth, temperatures of eight hundred degrees and roiling clouds of sulfuric acid. Venus is about 95% of Earth's diameter and 80% of its mass. The gravity is therefore about 90% or so. Geographically, Venus is rather different from Earth. It appears that unlike the Moon, Venus is a geologically live world, there is still volcanic activity in spots. However, Venus lacks plate tectonics. Why this is so is not clear. If may be that it is simply that the crust of the planet is thicker than Earth's, and so the Planet's heat is trapped within the core and mantle, slowly building up until the surface literally melts and reforms. Alternately, it may be that Venus is cooled or cooling, and Earth is geologically hotter because of leftover energy from the planetary collision that created the moon. Another view may be that the Tidal effects of Earth's moon lend Earth additional volatility. Without a large body stirring the pot, Venus is simply more tranquil. Whatever the reason, Venus’ geological processes are unlike our own. It appears that the surface of Venus is only about 800 or 900 million years old, although the planet itself is about five billion years old. This suggests that less than a billion years ago, the crust of the planet essentially melted, reshaping all of Venus, and erasing all previous geological history, including craters. The current face of Venus has been stable and unchanging since then. The rock formations on Venus are substantially steeper and more dramatic on Earth. The rocks on Venus are stronger, having had all moisture baked out of them. It is believed that because of its thicker crust, the internal heat had no place to go, and simply built up until the surface literally melted. It's likely that this has happened at least a few times prior to the last one. As to whether there's enough heat left to melt it again, no one knows. For this reason, Venus’ surface is relatively even. Mars for instance, has dramatic highlands and lowlands. A topographic map of Earth shows the same sorts of highlands and lowlands in the form of continents and oceans. Venus has only two areas, Ishtar and Aphrodite, that could be charitably called continents, although there are other high areas and islands. There simply is not a lot of range from high to low for much of the planet. If Venus had seas, then they would, for the most part, be relatively shallow. Continents and Islands would be generally flat. It's not clear what's going on, if anything, in Venus core. Although there are spots of volcanic activity on the surface, Venus like Mars lacks an active magnetic field. This implies that the core has cooled somewhat. Or it may be a factor of very slow rotation. In fact, Venus’ day is actually slightly longer than its year, and the planet is rotating backwards. There's no clear explanation for this, or for the fact that Venus always has the same face turned to Earth at its closest approach.

Burroughs Venus So, that's the Venus of our world. I'll take a leap and argue that except for a habitable environment, Burroughs Venus is essentially the same. Burroughs Venus is our Venus terraformed for habitability. Or perhaps not. In Burroughs universe, Earth and the Moon are hollow worlds with dwarf black holes in the center. This may well be the key to planet formation in Burroughs universe, in which case, we should expect the same for Mars and Venus. Mars exterior geography was shaped by two gigantic asteroid impacts in primeval times that left the Argyre and Hellas basins. Among the consequences of these impacts were gigantic areas of uplift and volcanoes on the opposite sides of the planet at the Tharsis bulge and Elysium volcano complex. The gigantic three thousand mile chasm, Valles Marinis that starts at Tharsis is a huge tear in the crust from the impact. The intensity of impact and the resulting debris fall deformed the planet, raising the areas around the impacts creating immense highlands and leaving vast lowlands in the northern hemisphere. So, if Mars is indeed a hollow world, like Earth and the Moon, we can assume that these impacts shaped the Martian interior world as well. The approximate locations of Hellas and Argyre are probably massive uplift and volcano sites, possibly still active, in the Southern hemisphere. The light of an interior Barsoom may well be from these burning volcanoes rather than a core sun. Tharsis and Elysium become, not depressions, but areas of savage chasms and cliffs, disordered chaotic territory where the shockwave travelling around the planet inside and outside met and spent its energy. Meanwhile, the tear of Valles Marinis may be reflected in the underworld and in fact, there may be an equivalent swamp, with water filled tunnels linking inner and outer worlds. The interior Mars may be a dark and swampy place, lit by red volcanoes, smoky air thick with sulphur. Life on the interior may, as in Earth's deepest trenches, be based not on photosynthesis but on processing hydrogen sulfides. For Venus, there's much less to go on for an interior world. Given its size, its possible that its interior sun still burns, rather than being confined as an inert carbon shell. But if it burns, we can only hope that it is within tolerable norms. However, it is unlikely that there are plate tectonics or active geography. If the crust is too thick topside, its probably too thick on the underside. Unlike Earth and the Moon, there are no hoos or passages, apart, possibly, from the poles. We can make no real comments about the geography of the inner world. One feature we might expect from both the Barsoomian and Venerian core stars/black holes, is that both planets would have strong magnetic fields more similar to Earth's. One possible alteration in a hollow Venus may be with its atmosphere. A dwarf black hole at the center might concentrate the heavier sulfuric elements in a ball around it, sorting out and leaving a much lighter mix of gases for the outer atmosphere. This may help to explain the difference between Burroughs atmosphere and the one we know. If that is the case, then Venus’ sun, with a mix of heavy gases in its outer shell is probably many times larger than Pellucidar's sun. It would be a large, hot, sputtering, orange red ball looming in the sky. It's possible that by virtue of its different construction, Burroughs Venus rotates more swiftly than ours does. But since we're unclear on the reason for the slow rotation, its hard to say that definitely. Carson notes cycles of day and night, but he might be fooled by differentials in the layers of cloud cover, with gigantic dark hemispheric clouds creating the illusion of night. It may seem lunatic to be discussing hypothetical inner worlds for Mars and Venus, but I would suggest that the gentle reader go back and take a look at my discussions of Pellucidar and the Moon's Va-nah. Hollow worlds may well be the rule for Burroughs Universe, and if that is a likely case, then we need to acknowledge it.

Looking for Matches on the Planet of Love So, if we try to match the current geography of our Venus, with the known geography of Carson's Amtor, how close does it come. To answer that question, I would refer the reader to a series of topographical maps: The Bright Map: This one is the most richly coloured and has the benefit of giving many of the features discernible names. So, it's a good reference map, the highland or ‘land’ areas are generally called “Regio”, while the lowlands are generally called “Planitia.” Unfortunately, its handicap is that it is a bit too richly coloured, making it a bit awkward to discern. The Green/Blue Map: This one is much better, particularly in allowing us to distinguish broad lowlands in blues, which would represent oceans and seas, from broad highlands, mostly in greens, which would represent islands and continents. With respect to this Map, I think that it comes closest to being a useful model for Carson's Amtor, with the exception that the sea level is a little low. There are areas which are obviously Islands that are tenuously connected to mainland. Elevate the sea level a little, and those areas become true Islands and Amtor comes into focus. The Green/Blue Map is the best for direct comparisons with the adjusted Amtorian maps, and it can be used particularly well with Huckenpohler's cylindrical projection. The two actually have a reasonable resemblance to each other.

On Viktor's adjustable topographic map, we can readily see the different extremes of Martian geography, and experiment with how that world would have looked with oceans of varying depth. We can do the same thing with Venus, although Venus's range of altitudes is much less. Generally, in referring to Viktor, it appears that the closest matches to Burroughs Amtor come at about 350 to 550 meters sea level. 440 meters is probably the single best approximation to Amtor. Our first geographical target therefore, is a continent sized mass, spanning a substantial portion of the Equator. This continental mass needs to have highlands within it, and a hefty set of peaks. Is there any such place, on Venus? Why yes there is. It's called: Aphrodite Terra. Amazingly enough Aphrodite Terra is a loosely scorpion shaped continental mass, running along the equator for about forty per cent of the planet's circumference. At its center and along its length is a series of fierce highlands and mountain ranges. It includes Ouda, Thetis and Atla regios. Which would give us the interior highlands and mountain ranges. At Viktor's 350 to 550 sea level, Aphrodite Terra doubles in size while retaining its same basic outline and stretches across a fair portion of the Equator. One of the more interesting things about Carson's equatorial continent, is he describes an immense 500 mile long lake in this continent in the northern hemisphere bordering the northern sea. And in fact, there is a geographical feature which seems to answer that description. A large circular lowland between the ‘head’ and ‘body’ of the scorpion continent, Ouda and Thetis Regio, which is quite apparent on both the Blue/Green Map and the Viktor Map. Against all odds, we seem to have found the Lake of Japal. And of course, behind it would come rolling plains, escalating to foothills and eventually the mountainous terrains of the Regios. This is a remarkably good match. Of course, Burroughs continent has a ‘leg’ towards a southern pole. Aprhodite Terra does not leg towards the pole, but it borders close to and even touches another shallower land mass, described as Alpha Regio, that does actually bridge the equator and the polar regions. You can check out Alpha Regio's location on the Bright Map, but the other maps, particularly Viktor's give a better view of its elevation and relationship to Aphrodite. Indeed, at lower sea elevations, around 440 or lower the two continental masses do join, trapping an inland sea within. The total area range of the two land masses would probably amount to about sixty per cent of the planet's circumference. Burroughs Amtor maps and references do not disclose an inland sea, but then, the Amtor explorers clearly were far from thorough. Conceivably they never found it. Or perhaps they did find it and mistook it for the other shore leading of the continent facing the world ringing southern hemisphere ocean. Or it may be that over time, this inland sea would have drained or dried. In any case, considering the inherent defects which must be inbuilt in the Amtor map, we can be allowed a fair amount of license. Unfortunately, the leg seems to be on the wrong side.... But then, this is on a planet that rotates backwards, and as reported by a man famous for getting his directions wrong. So it's hardly the fatal flaw it might otherwise be. Oddly though, it seems to be a consistent flaw. Later on, when we look at ‘Anlap’, the Vepaja archipelago, and even the Sanfal archipelago we continue to see these reversals, left is right, east is west and vice versa. Who knows, perhaps Carson really is dyslexic. At the South Pole, particularly at the depths of 350 to 550 meters sea level on Viktor's map, there South Pole is largely ocean. However, the Alpha Regio land mass does reach down to the pole, and there are indeed low lying subcontinental masses or Madagascar mass, which would serve quite well as Amtor's Karbol region. The area bears remarkable similarities to depictions of the south polar area in some of the fan generated maps. The other major land area mentioned by Carson is Anlap. Only partially depicted on the maps, Carson makes his way from the north to the south, through at least two mountain ranges and a vast interior plain. Once again, we have a match: A rambling equatorial continent made up of Asteria, Beta, Phoebe and Themis Regios, which seems to orient north and south. You can locate this region on the bright map, but both Viktor's and the Blue/Green map give a better idea of its dimensions and shape. This ‘Anlap’ contains three mountainous regions running east and west, and a large broad plain in the center region. On the one side, it is surrounded by extensive lowlands, a large ‘sea’, on the other side, it is close to the Equatorial Aphrodite Terra continent and may even be loosely connected with it. Taken together, ‘Anlap’, Aphrodite and the ‘leg’ effectively take up most of the equatorial region. The only problem is that like the ‘leg’ it is reversed, opposite to where it should be according to Carson. It lies to the East of the likely Vepaja, not to the west. But then, as we'll see going along, this is a consistent trait, applying to other geography as well. In short, within the current topography of Venus, we can find the three major land masses of the Southern Hemisphere of Amtol, roughly about where they should be (allowing for reversal), and as bonuses, we have both the giant lake of Japal, and the mountain/highland regions for both Aphrodite and ‘Anlap’ in the approximately correct regions. It's far from perfect and somewhat muddled, but the degree of rough correspondence is remarkable. So, where is Vepaja? Where are the Vepajan or Sanfal archipelagos? The answer to that is ambiguous. It is, obviously, too much to expect to see specific islands close to the shapes depicted on Burroughs map. Frankly, we were supernaturally close between Mars and Barsoom. Venus does not have that degree of fidelity. However, at various elevations, large ‘Islands’ come into view which might well serve as Vepaja, Trambol, Zando, Sanfal, Malpi, Donuk, Movis and Nok and/or island/peninsula Ator. As to which elevations provide the best ‘Islands’ and how these elevations affect the shape of the major land masses, I will leave it to the reader to explore with Viktor's map. Looking at the Green/Blue Map, however, we can clearly see, in the southern hemisphere, roughly directly beneath Atla Regio (the tail of the Aphrodite scorpion) a large ‘Island’ called Imdr Regio on the Bright Map. On other side, not terribly close, there are two other large islands, neither of which is specifically identified on the Bright Map (I suppose I could find them on topographic identified hemispheric maps, and anyone who wishes to can find them quickly and easily, but frankly, I've made this too complicated as it is). They are easier to pick out as distinct areas on the Green/Blue Map. One of them is below the area between Themis and Atla Regio on Aprhodite. The other is harder to spot, since it is at the edges of the Blue/Green map and literally bisected, it appears as two small splotches at each end. Nevertheless, it appears to be a genuine ‘Island.’ Of the three Islands, the centre one, Imdr Regio seems to be at the latitude nearest the equator, the other two are closer to polar latitudes. This makes it a relatively good match for Vepaja. Meanwhile, of the other two, one seems significantly smaller than the other, as Zando is significantly smaller than Trambol. The order, what we can make out of it, seems reversed, with the actual Venusian order being Zando, Vepaja and Trambol. On the other hand, the ‘leg’ to the pole that is the Alpha Regio region is also reversed. So on this basis, I'm strongly leaning towards the original Amtor map being reversed, either by Carson, or by the juxtaposition of right and left because of the planet's retrograde rotation. It's hardly a perfect match of course, but against all odds, there does seem to be a loose archipelago of three very big Islands in Venus’ southern ocean beneath the Aphrodite continent. That's a hell of a lot better match than we are entitled too. I'll also note for the record, that the shapes of these Islands seem a lot closer to people like Huckenpohlar's and Broadhurst's reconstructions than to the originals. So, they may well be right. Looking towards the opposite side of the planet, much closer to the Equator, Burroughs records a second archipelago of large islands: Sanfal, Malpi, Donum, Movis and Nok. In fact, if we look to the Green/Blue Map, we see a series of large islands near the equator, strung out in a line (with a leg or two), which would serve very well as our archipelago. On the Bright Map the area is identified as Eistla Regio. The only problems are that once again, they seem to be reversed, which is at least consistent with the other features of actual geography, it seems the entire planet is reversed from Carson's maps and descriptions, east is west and west is east. Much more problematically they seem to stretch or lie a bit on the northern hemisphere. But here too, there is an explanation... The Amtor cartographers had no concept of even the existence of a northern hemisphere, their cosmology would not even allow for it. But on the other hand, as I've noted previously, they could hardly be said to know where the equator was, or even have the academic tools to recognize or define it. So, if their sailors actually wandered over the Equator and into the northern hemisphere, charting the great islands there, those Islands would simply be incorporated into the ‘southern hemisphere’ saucer. They'd make some guesses as to location or latitude based in part on the weather or climate around these Islands. So this may explain the Sanfal chain's being a bit too far north. There is a further bit of corroboration in that the ‘Sanfal’ chain is actually relatively close to the ‘Anfal’ continent, despite being in the northern hemisphere. Carson is in the vicinity of south ‘Anlap’ for both his journey to Japal Lake in Escape on Venus, and his journey to Donuk in Wizard of Venus. But the journey to Donuk is clearly much shorter, a matter of hours, than the journey to Japal Lake, which takes most of a day and a savage storm. This seems to agree with our provisional locations. Frankly given the impossibility of Burroughs knowing anything about the surface of Venus, we should consider ourselves astonished that we can find features that have even the loose resemblance to the Vepaja and Sanfal archipelagos that we have so far. In fact, we've found some quite decent matches, and although we've had to make adjustments to make those matches fit, these are reasonable and consistent adjustments. Further, and oddly, the oceans of Venus, with their shallower and rugged beds, seem to sport a massive profusion of small islands. They are in fact more heavily dotted with islands of various sizes than Earth's oceans. The only region on Earth remotely comparable is Pacific polynesia, and the Islands of Venus seem rather more numerous, larger and more randomly distributed. This wealth of Islands recalls what Carson was told, that Vepaja originally encompassed an Empire of ‘a thousand Islands.’ In the end, of course, Unravelling Amtor does not quite give us Venus, or vice versa. Given the likely inherent problems in Amtor's map making, even if Burroughs was describing the actual planet, it wouldn't match up. Nevertheless, we have found a series of odd and striking parallels, and there are reasonable explanations for the discrepancies. It is good enough, and close enough, that some enterprising cartographer could take the Blue/Green Map as a starting point and lay Amtor over it. The correspondences between the real and fictional world place them as close cousins, and with some reasonable allowances and adjustments, one might easily do for the other. It's not as eerily close as Barsoom/Mars, but Amtor/Venus is actually far closer than it should have any right to be.

Assuming Venus Equals Amtor, What Conclusions? Let's take the game a few steps further. Assuming that the geography of Venus is actually the geography of Amtor, not really impossible given the quality of Amtor's maps, what conclusions could we draw in terms of the planetary dynamics? First, it is worth noting that in Aphrodite Terra and its related land masses neatly divide the oceans of northern and southern hemispheres. The geography runs east to west along the equator. On Earth, geography roughly runs north to south: North America and South America, Europe and Africa, East Asia to Australia, both the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans straddle both hemispheres. On Earth, this essentially means that the two hemispheres share weather and climate, biological populations of fish in the oceans move easily between the hemispheres. Meanwhile, plant and animal life on land are divided by latitude, moving from arid arctic steadily towards the tropical. On Venus, however, these situations are reversed. The weather patterns of north and south hemispheres are likely to be completely distinct and largely unrelated. A land mass running the length of the Equatorial region means that equatorial heat will not be distributed north and south, but rather stay there, building to extreme temperatures. Oceans soak up and distribute heat, land masses concentrate it. Thus, a point on the Sahara desert will be a lot hotter than spots at the same latitude on the Pacific or Atlantic Oceans. Strabol really is hellishly hot at points. The polar regions are also probably stable cold spots. On Earth, the Polar regions are ice covered, but this is not necessarily a rule. Rather, two geographical flukes give Earth its ice caps. The north pole is essentially a trapped sea, with the Arctic Ocean being ringed and closed in by the upper regions of Siberia, Scandinavia, Greenland, Alaska and the Canadian Archipelago. Because there is nowhere for water to flow easily, the trapped waters keep getting colder and colder and an ice cap forms. In the southern hemisphere, there is a continent at the south pole. Antarctica is land, so snow falling has no place to go and simply sits there, building up into a heavier and heavier sheet of ice, and eventually the whole thing glaciates. Because the glacier is sitting on land, it is stable and relatively permanent. It is difficult for ocean waters to melt. The situation of Venus poles is opposite. On Venus it is the South pole which is open water surrounded by land. On the north pole, there is a polar land mass. The north polar area is the area of Ishtar Terra, Venus other true continent. Ishtar Terra is much smaller than even Aphrodite Terra, but its elevations are even higher, it sports the planet's highest mountain, Maxwell Montes. The high elevations suggest that Ishtar Terra is likely to be colder than the south pole, and may well be the only spot on the planet where glaciation occurs. The high altitude and latitude make glaciation possible, and the extensive land mass makes for stable glaciers. The north polar land mass is shaped like a ‘C’, suggesting that on a seasonal basis it periodically freezes a fair chunk of the ocean waters (assuming that the pole glaciates, but even if it doesn't the cold region will reduce the temperature of waters in its region). Effectively, the shape of the north polar land mass as a cold, perhaps glacial land surrounding a captive sea or bay means that it acts as a sort of refrigerator to freeze or chill the arctic water. The open bay also means a free flow of water, and therefore a high degree of interraction with warmer southern waters. This means strong cold currents moving southward, which will be very fertile for fish. The strong cold currents would be equivalent to the South Pacific El Nino current, which is the basis of the Andean fisheries. The converse, of course, is that you would also get hot currents moving north, like the European gulf stream. This may result in large islands between equator/pole currents with hot and cold sides, and it may result in small islands being permanently hot or permanently cold, depending on which current they happen to be located in. The actual latitude may be less important in describing an Island's climate, with very warm Islands being at unusually high latitudes, or very cold Islands being at low latitudes. It would be unpredictable, and heavily influenced by currents. Count on the weather on large islands being changeable and erratic, full of volatility. Weather unlucky smaller islands will be consistently somewhat miserable. Ocean travel in Venus’ northern hemisphere may well be at the mercy of powerful and implacable currents. Sea routes are probably laborious or indirect, cautious sailors hug the coastlines, and those who do venture into open seas probably travel extended ‘circuits’ on the currents. The southern hemisphere polar region, though cold, is not nearly as elevated as Aphrodite Terra. Indeed, what we have here is a southern polar sea only loosely bounded by land masses. The land masses are far less inclusive than those ringing our own arctic sea, which means that there is far more and far easier exchange of waters with surrounding temperate seas. This makes it very unlikely that the south pole would glaciate year round. At best, you might get some small glaciation on some of the surrounding lands, and perhaps seasonal land glaciation and sea ice formation. My guess, however, is that you probably won't be getting a south polar ice cap, even in winters. Because the south pole is probably not glaciating, it has trouble trapping its cold waters, and thus is probably somewhat warmer than the north pole. The relatively open exchanges or geography with the temperate seas means that the south pole sea is not well shaped to create strong cold currents. There will be cold currents as well as hot ones, but by and large, they will be only a fraction of the strength of the northern ones. They'll be more lukewarm and they'll be slower and less energetic. For this reason, the Southern hemisphere ocean is probably a lot more placid, with seas that are easier to travel by wind, and islands that are more accessible to local trade. The environment and climate on Islands, even large Islands will be much more stable and much more determined by latitude. The weather will be more consistently pleasant. In both hemispheres, the extensive shallow seas means that the oceans are comparatively much richer than on Earth. The biological productivity in many areas will be along the lines of Earth's grand banks. Because of greater current circulation, the north will be more productive. But the southern hemisphere will still be rich. Meanwhile the biological populations of north and south hemisphere seas are also probably strictly divided and highly distinct. There may be some mixing, but by and large, the overall populations and distributions of species are highly unique to each. In particular, the apex feeders, the really big fish, sharks, whales, etc. will be very different. One might should anticipate large surprises, gigantic jellyfish, cultures of sea-men or mermaids, great crustaceans, intelligent sharks or fish the size of ocean liners. Given the more extreme but fertile conditions in the northern hemisphere ocean, evolution should move faster there and species will be hardier and more aggressive. If you get intelligent sharks or mermaids they'll likely be in the northern hemisphere. Meanwhile, the southern hemisphere offers an almost as rich, but less volatile environment. This is a good ground for creatures to grow very large, as in giant jellyfish or ocean liner sized fish. On land, the bulk of Ishtar Terra and the great land masses tend to be distributed around the equator. This is about the same as having the Siberian land mass in a tropical jungle latitude. It's a huge rain forest area, biologically productive, several times the size of the Amazon or Congo rain forest basins. Ishtar terra, due to its central position is probably well watered by both hemispheres. So except for the uplands, much of this continent is probably tropical savannah and rain forest. In the highlands and mountainous areas, due to elevation and the mixing of winds from upper latitudes, expect these areas to be cold, damp, rainy and almost perpetually cloudy. Adjacent upland areas will be chock full of fast moving streams and rivers coming down from the mountains and watering the rest of the continent. The absence of major latitude crossing land mass suggests that migratory animals will not develop. In North America, Europe and Asia, both animals and birds migrate vast distances to avoid weather. This is possible because of the North/South orientation of continents. On Venus, where the orientation is east and west, most land on a major land mass is within the same latitudes. Not much chance of migration doing any good, instead, the animals have to tough it out in their local regions. Animal herds will therefore be smaller, and as latitudes move away from the equator, the productivity of animal life will drop... Basically, more grazing required for fewer bison. Animals will tend to be smaller, but within ranges. After all, elephants are not extremely migratory, but pretty big, on the other hand, their migratory cousins the mammoths grew to be twice their size. One very relevant piece of information relates to the shallowness of the lands and seas. Play around with Viktor's map and we see that even relatively modest drops in sea level will start to connect large islands either to each other or to land masses. On Earth, we have relatively deep seas, so quite large masses of water have to be locked up in glaciers to make the sea level drop. The antarctic Ice cap, which extends over something like five million square miles to a depth of miles, if it were to melt, would raise water levels by something like two hundred feet. Meanwhile, the glaciation of North America during the last ice age, locked up so much water that sea levels dropped a few hundred feet. Of course, as noted, the oceans are very large and very deep. Amtor's seas would seem to be both smaller and shallower. Earth is 75% water covered. Amtor seems to be around 50 to 60%. Because the seas are smaller and shallower, you don't need to lock up as much water to produce large drops in sea level. It's quite possible that a Venusian Ice Age which resulted in glaciation at both poles would drop the sea level quite a bit. Of course, that would expose more land, which would result in more heat concentrating in local areas. So the result would not necessarily be a colder planet. In fact, the equator and temperate regions, continents and large islands would probably be as hot or hotter than before, until you reached arctic latitudes. The Seas would be substantially cooler, and so would the small islands. The seas would also likely be biologically richer and more productive. But on land, you wouldn't notice much more than that the nights were colder. But there would be one very important consequence of substantial drops in sea level: Land bridges. On Earth, with the development of plate tectonics, land bridges have fallen out of favour. But before we got our head around the idea of continents moving around, land bridges were the favourite theory to explain how different species of plants and animals managed to get from Asia to North America, or from Africa to South America, or even between parts of Asia and Africa. Well, on Venus, the continents and islands do not move around. The Venerian geography barring some volcanic activity, has pretty much been stable for about 800 million years. But the seas are shallow, so actually, if the seas drop, we would get land bridges connecting most of the major chunks of land. Which, in turn, means that the flora and fauna of Amtor, the plants and animals, would have a route to travel out to islands, other continents and isolated regions. This explains why the bison-like Baspo, a creature of the Aphrodite Terra continent is also to be found on Vepaja. In fact, play around with Victor's map a bit, and we’ll

see that with relatively modest drops of elevation, produced by ice ages,

we'll wind up with a pretty uniform range of plants and animals on most

of the major land masses on this planet, and extremely widespread species

of animals across much of the world.

There would be plenty of permanently isolated small islands of course, but the result would probably be interesting though not terribly significant local faunas, like the Galapagos tortoises and iguanas, or the Mauritian dodo birds. One final geological note. Venus as we know it is mostly composed of baked basalt with extraordinary structural strength because there is no moisture to weaken the rock. This has resulted in sheer cliffs and mountains. If Venus became wet, then it is likely that the baked basalt would eventually become wet, and this would result in structural deterioration and erosion. Mountains would subside and collapse, Island areas might sink, other areas might rise or bubble upwards as water and moisture seeped into cracks and crevices. Eventually, Venus basalt would be no stronger then terrestrial basalt. It is not clear how long this process would take. A few factors suggest that it would happen very slowly. First, ‘pre-baked’ basalt would be much more resistant to humidity or moisture infiltration than basalt originally formed in water rich environments, so susceptibility or softening to humidity is likely to take a long time, if ever. Second, there is a vast amount of basalt and the sheer volume of rock, including rock piled on top of or buried under rock is also likely to take a long time to affect. So consequently, the ‘softening’ of Venus’ basalts would probably take tens or even hundreds of millions of years. The result would be some slow alteration of the shapes of islands, coastlines and mountains. Venus seems less geologically active than Earth, and without plate tectonics, you would not get Earthquakes as we know them. On the other hand, the ‘softening’ of the Basalts would occasionally result in subsidences, avalanches, earth shifts and collapses, creating small local quakes and disturbances. It is also likely that with water at work on Venus, you would start to see other types of rock forming, particularly sedimentary and metamorphic. However, the geology and geological diversity of Venus would have less time to form and so would probably be more restricted in comparison to Earth. I would expect that the soil, sand and gravel cover would be thinner, and there would be more naked rock. Venus's land surfaces would probably somewhat resemble the Canadian shield. In turn, this means that the organic material/biological activity is all in the surface or in the system. Not much topsoil or at best, very thin layers. So, shallow root systems which stretch out widely. A good storm probably has a fair chance of knocking over medium sized trees. Because of the underlying nature of the rock/soil structure, the ecology of Venus is very rich but very delicate, and not terribly susceptible to manipulation. You could come to a lush fertile forest or jungle, clear it to plant crops.... And discover that the next season, you've got nothing but naked rock. Agriculture would be much less portable on Venus. This might explain why, on Amtor, there seems to be so little human penetration of the continent and why so much of it is in its wild state.

Getting to Amtor So, we have Venus, how does it become like Amtor? There are three possible explanations. One, which I've canvassed previously, is that if Amtor like Burroughs Earth and Moon, is a hollow world, then that hollow interior, including the hypothetical dwarf black hole, has probably altered or affected the atmospheric composition. That's theory one, and its restricted to the Burroughs universe. Another possibility has been touched on in my previous discussions of Pellucidar, Va-Nah and anomalous intelligent species on Amtor. That is, it is possible that Earth itself occasionally discharges a bio-magnetic field to other worlds which not only materializes life on these other worlds, but modifies the atmospheres and liquids of the other world consistent with that life. That's theory two, and its also restricted to the Burroughs universe. A third possibility arises. Basically, take a huge comet, something dozens or hundreds of miles in diameter and whack it into Venus really hard. The impact and shockwave superheats the atmosphere even further and literally blows chunks of the atmosphere away, reducing density. This has to be a really really big comet in order to hit hard enough to literally blow the atmosphere into space. To be on the safe side, you might need a few. The other reason you need a really really big comet is so that the comet itself doesn't evaporate into space. Comets are essentially made of rock, water and volatiles. Lots of water. They're big space travelling balls of slush. So a small comet hitting, its water is incinerated and just blows off into space with pieces of the atmosphere. In fact, since the elements of the comets water, hydrogen and oxygen, are fairly light, they'll blow off into space much easier than the heavy atmospheric constituents. So, you want your comet to be really big so that a fair amount of its ice and light elements make it to the surface. Hit with a big enough comet, or a series of big comets, and you've thinned out the atmosphere appreciably, and you've deposited a lot of ice and light elements. Hopefully, the freed water and light elements react with the atmosphere, purging it of a lot of toxic/corrosive stuff, and eventually, you might get a world with a relatively light, somewhat breathable atmosphere and large seas and oceans. Now, if the greenhouse effect doesn't get you, we might be in business. But hopefully, the debris and particles thrown into the upper atmosphere reflects most of the light and keeps the temperature down. Of course, you might have to keep sending stuff up, but there you go. [Actually, this might explain one phenomenon on Amtor, the parting of the clouds, and the incineration of whatever is in the path of direct sunlight. Perhaps this is the mechanism whereby superheated convection currents, a kind of heat elevator, lift low level material to the upper atmosphere to protect the planet by creating a barrier to most of the solar energy.] The third option, of course, explains how Venus becomes a somewhat habitable watery world, but hardly explains what life is doing there, or how diverse or complicated that life is, or even what humans are doing there. Note that if this has happened in the last 800 million years since the surface stabilized, then that simply isn't enough time for life to evolve or get to the point where it is on Amtor. On Earth, the earliest life seems to go back something like two or three billion years as unicellular organisms. It floated around for a long long time before getting active in the last five hundred million years, and only really got impressive on the land in the last two hundred million years. For Venus to reach Earthlike levels, its early life would have to shortcut in only a few hundred or even tens of millions of years stuff that took Earth billions of years and some flukes. Possible, but not too likely. And for the record, you couldn't have your comet bombardment before 800 million years ago, because 900 million years ago, the surface melted. So even if you had created a Venusian paradise a billion years ago, a mere hundred million years later, all that work would have been undone, the surface would have melted, the water vaporized, the atmosphere filled with volcanic gases causing a runaway greenhouse effect, and you'd end up with our Venus. So, while option three is actually the root that humanity might take in the future, if it decides to Terraform Venus, it is only a partial explanation for how Venus became Amtor in the Burroughs Universe. Of course, we might anticipate in the dim unrecorded past of the Burroughs universe, that some past alien civilization, or even lost super-advanced human civilization, or possibly even time travellers from our future, might have gone dropped a lot of wet comets on Venus and Mars, terraformed the places, seeded them with life and eventually with humans. Burroughs offers no evidence on this point, but it's a strange universe. So who knows? And with that, gentle reader, I'll release you.

I hope that you've enjoyed this little journey, possibly learned a few

things and perhaps hope that it might inspire you to your own flights of

fancy. Good luck.

|

ERBzine WEB REFS

|

for Den Valdron's Fantasy Worlds of ERB |

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

BILL

HILLMAN

Visit

our thousands of other sites at:

BILL

AND SUE-ON HILLMAN ECLECTIC STUDIO

ERB

Text, ERB Images and Tarzan® are ©Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.-

All Rights Reserved.

All

Original Work ©1996-2006/2010/2019 by Bill Hillman and/or Contributing

Authors/Owners

No

part of this web site may be reproduced without permission from the respective

owners.