PULP PELLUCIDAR

Contents

The Inner

World, Fact, Fiction or Faction

Inner World

Fictions, Before ERB

Pre-ERB Pellucidar References

Post ERB Pellucidar References

The

Sunless City - a Pellucidar Case Study

The

Inner World, Fact, Fiction or Faction

The origins of the hollow world theory actually seem to

have their roots way, way back in pre-Copernikan cosmic theory.

Let's back up a bit. Copernikus was the guy

who came up with the notion that the Earth revolved around the sun, and

not the other way around. Before that time, Greek and middle

eastern astronomers led by Ptolemy (no relation to Cleopatra's dynasty)

were developing a peculiar and somewhat biblically inspired theory of the

universe.

They

believed that the Earth was at the center of the universe.

Fair enough. However, it was pretty clear that there was a sky above

the Earth. This was believed to be a huge dome or globe called

the firmament. This was what kept the stars up, they were physically

embedded in the firmament, like spackle on a ceiling. All right.

Fair enough.

They

believed that the Earth was at the center of the universe.

Fair enough. However, it was pretty clear that there was a sky above

the Earth. This was believed to be a huge dome or globe called

the firmament. This was what kept the stars up, they were physically

embedded in the firmament, like spackle on a ceiling. All right.

Fair enough.

The notion of a physical firmament, a roof on the world,

was a very ancient one, and references to it can be found throughout the

bible. This archaic cosmology was then the foundation of notions

of heaven and hell. Heaven lay above the 'firmament' somewhere.

Hell lay beneath the Earth. Actually, above the firmament it

was pretty wet... After all, rains fell from the sky, and when God

decided to destroy the world, he opened up the firmament and let the flood

rains come down.

This is commonly known as the Ptolemaic

model, and it stuck around like an anchor around the neck of astronomy

for fifteen hundred years. Both medieval and early renaissance

European observers, as well as Arab observers adopted it and tried to refine

it as the problems accumulated.

Now, the thing was, medieval astronomers were basically

working with what they had. They were stuck with the firmament

theory. Well, they started to notice that the sun and the moon

seemed to be moving in ways different from the rest of the sky.

And then they noticed that the planets were also moving at different rates.

To make it worse, some of the planets would occasionally seem to move backwards

in the sky, before hiccuping and resuming their normal direction.

This was tricky. If there was only one firmament,

then everything in the sky should be moving at the same rate.

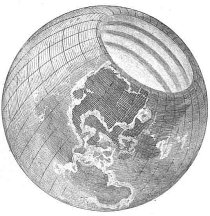

So, obviously, there was more than one firmament. Medieval cosmology

soon came up with a universe made up of a series of transparent spheres,

each nested inside the other, starting with the firmament and ending with

earth.

Okay, with us so far?

Let's not be too hard on these guys. Notions

of gravity, centrifugal motion, Newtonian physics were still far in the

future. Some things fell to or stuck to Earth.

Other things stayed up in the sky. They had to come up with

something.

Anyway, Copernikus came along and smashed the model of

concentric spheres, and then Newton came along later and put the kibbosh

on the whole thing. The notion of a cosmos as spheres nested

within spheres wound up on the dust heap of wacky ideas.

But you know, there isn't a notion out there that is so

dumb that some complete lunatic won't dust it off and run with it.

Hell, there are people who think George W. Bush isn't a cowardly moron,

so obviously, it takes all kinds.

So, we've got this really nifty theory of concentric spheres,

and its not applying to the Universe in general. But you know, there

was a lot of unnecessary veneration of ancient thinkers. So people

were reluctant to just throw away a perfectly good idea.

Okay,

if there weren't concentric spheres beyond Earth... Maybe they were

within Earth itself? In 1692 Edmund

Halley (discoverer of Haley's Comet) published an essay suggesting

that the Earth was a hollow sphere with a shell only 500 miles thick.

Within it were other hollow spheres corresponding in size with Venus and

Mars, with Mercury as a solid core. These spheres were inhabited

or at least supported life, and there was light for the whole thing, coming

from somewhere or other...

Okay,

if there weren't concentric spheres beyond Earth... Maybe they were

within Earth itself? In 1692 Edmund

Halley (discoverer of Haley's Comet) published an essay suggesting

that the Earth was a hollow sphere with a shell only 500 miles thick.

Within it were other hollow spheres corresponding in size with Venus and

Mars, with Mercury as a solid core. These spheres were inhabited

or at least supported life, and there was light for the whole thing, coming

from somewhere or other...

You can sort of see where Edmund came up with it.

Smoking a little opium perhaps, observing that the inner planets were all

different sizes that could conceivably fit one into another, refurbishing

concentric spheres... I can't actually say that Edmund came

up with it, though he can take the blame as well as any other.

Then

in 1721

Cotton Mather,

taking time off from burning witches, took up the idea in The Christian

Philosopher. Of course, I'm not suggesting that Mather

was a disciple of Edmund Halley in any way. One was a noted astronomer,

the other was a vicious religious fruitcake. I suspect that they

probably never met and almost certainly wouldn't have gotten along.

Then

in 1721

Cotton Mather,

taking time off from burning witches, took up the idea in The Christian

Philosopher. Of course, I'm not suggesting that Mather

was a disciple of Edmund Halley in any way. One was a noted astronomer,

the other was a vicious religious fruitcake. I suspect that they

probably never met and almost certainly wouldn't have gotten along.

But these two examples show that the notion was sort of

floating around there in the thinking of the late 17th and early 18th centuries.

It was hardly based in science, but rather, a sort of muddy melange of

religious and philosophical conjecture. There wasn't really

anything that could recommend the theory, apart from a certain sense of

quasi-biblical symmetry. So I assume that eventually, it would

have simply died away like many other junk theories. What it

needed was a truly dedicated lunatic.

The

dedicated lunatic was Captain

John Cleves Symmes of the US infantry. Symmes makes it

into the history books, not just for his utter obstinacy in the face of

all reason, but for the relentless unswerving dedication he brought to

his theory. He was like a dog with a bone. He refused

to let it go, and in fact, spent so much time and effort preaching his

theory he actually spread the idea far wand wide and made enough converts

to keep it propagating.

The

dedicated lunatic was Captain

John Cleves Symmes of the US infantry. Symmes makes it

into the history books, not just for his utter obstinacy in the face of

all reason, but for the relentless unswerving dedication he brought to

his theory. He was like a dog with a bone. He refused

to let it go, and in fact, spent so much time and effort preaching his

theory he actually spread the idea far wand wide and made enough converts

to keep it propagating.

After fighting in the war of 1812, Symmes retired from

the army and came up with the goofy notion that the Earth was hollow.

Better than that, the Earth wasn't just hollow, but there was another Earth

inside it. And another. All in all, he thought that the

Earth contained five concentric spheres, each nested inside the other like

one of those Russian dolls. And most amazingly, both the inner

and outer surfaces of each sphere, including our own, contained vegetation

and animal life. Each sphere contained polar openings, several

thousand miles across through which you could use to access the inner world.

Now

hold on, why would the insides of the spheres be occupied?

Well obviously because the inside of the outer sphere, the firmaments around

the Earth were occupied by stars and planets. Thus, it seemed reasonable

that there would be something on the inside of the Earth, and it seemed

sensible it would be the same sort of stuff as on the outside.

Now

hold on, why would the insides of the spheres be occupied?

Well obviously because the inside of the outer sphere, the firmaments around

the Earth were occupied by stars and planets. Thus, it seemed reasonable

that there would be something on the inside of the Earth, and it seemed

sensible it would be the same sort of stuff as on the outside.

Well, remember what I said about being generous with those

early astronomers who were trying to make a firmament theory work?

Well, forget I said that. Mather and Halley were dabblers,

playing with the idea and moving on to their private concerns.

Symmes was a lunatic, a crackpot, a flake, and the people of his day knew

it. Hell, this was after Copernikus and it was after Newton.

There was just no Earthly reason to endorse his goof ball theory and he

was roundly ridiculed. He died in 1829, a barking lunatic to the

end.

But his views lived on. Somehow, he found disciples,

and two books were published expounding his theories. James

McBride's 1826 opus Symmes

Theory of Concentric Spheres and Americus Symmes' (his son) similarly

titled work of 1878.

Thus,

these polar holes have come to be called 'Symmes

Holes.' It's remarkable how he was able to give his name

to a piece of utter nonsense and have it stick.

Thus,

these polar holes have come to be called 'Symmes

Holes.' It's remarkable how he was able to give his name

to a piece of utter nonsense and have it stick.

Now, okay, I've been hard on the guys. But arguably,

there was some evidence to suggest that peculiar things were going on at

the poles. Compasses became inaccurate as you approached the

pole, there were strange lights in the sky from aurora borealis or from

optical scattering. As they approached the pole, for instance, many

explorers reported seeing two suns in the sky, or images of spectacular

lands and even cities reflected in the clouds. Well, you can

do a lot with ice crystals and alternating layers of cold air, but explorers

didn't know this. Instead, what they knew was that the closer

you got to the poles, the more weird and unexplainable phenomena there

was.

The

Auroras were particularly tricky. They were curtains of light shining

in the sky, seeming to emanate from the pole that were unconnected with

the sun or other light sources. Maybe they were coming from

a polar opening, maybe the light was shining out not from above the earth,

not from on the earth, but from inside the earth!

The

Auroras were particularly tricky. They were curtains of light shining

in the sky, seeming to emanate from the pole that were unconnected with

the sun or other light sources. Maybe they were coming from

a polar opening, maybe the light was shining out not from above the earth,

not from on the earth, but from inside the earth!

James McBride and Americus Symmes went at it like that,

and they assembled a huge conglomeration of data and mysteries, such as

migration routes of animals, unseasonably warm traces from northern regions

(dust and pollen blown up from the inner world), frozen mammoths (critters

from the inner world who had wandered to the surface and froze to death),

travellers reports, astronomy, physics and whatnot to support old man Symmes

theory.

Around

the same time, Ignatius

Donnelly

was doing the same thing as he developed his theories of the lost continent

of Atlantis. And to be honest, there's a certain persuasiveness

to this reasoning. These guys basically came up with an idea,

and then they cunningly proceeded to cherry pick evidence, including endless

unexplained phenomena that cried out for answers, stealthily fitting it

into their theory, until it seemed to be a massive edifice buttressed with

an irresistible wealth of facts. But really, you can pretty much

use the same methods to prove anything.

Around

the same time, Ignatius

Donnelly

was doing the same thing as he developed his theories of the lost continent

of Atlantis. And to be honest, there's a certain persuasiveness

to this reasoning. These guys basically came up with an idea,

and then they cunningly proceeded to cherry pick evidence, including endless

unexplained phenomena that cried out for answers, stealthily fitting it

into their theory, until it seemed to be a massive edifice buttressed with

an irresistible wealth of facts. But really, you can pretty much

use the same methods to prove anything.

There were a few wrinkles after that. A fellow named

Cyrus Teed came up

with a hollow Earth theory in 1870 that remarkably claimed that we were

all living on the inside, not the outside of the globe. The

less said about that, the better. He called his theory Koreshan

Cosmology, and renamed himself Koresh, which carries unfortunate connotations

today.

Dr. Cyrus Reed Teed

In 1885 a guy named William F. Warren wrote Paradise

Found, or the Cradle of the Human Race at the North Pole, which sported

the remarkable theory that the human race had originated in a primordial

garden of Eden in the inner world

Now, the next big shift that came was with a guy named

Marshall B. Gardner, who worked for a corset company which sounds a lot

more fetishistic these days than it was then. It's almost

certain that somewhere along the line, he became aware of Symmes theory,

probably through Americus Symmes' or James McBride's compendiums.

He even swallowed Symmes theory, almost. By

this time, the whole notion of concentric spheres had pretty much reached

its philosophical exhaustion. There was just no good reason for it,

and we have evidence that the concentric spheres were vanishing from hollow

earth theory, since I've read a novel published in 1905, well before Gardner

came along, that had an inner earth but not concentric spheres.

Its an odd little paradox, the only reason that you had

a hollow earth theory at all was to get the space to put the spheres in.

But once the hollow world was established, you didn't really need the spheres.

Gardner still saw a lot of evidence

for a hollow world.

Gardner's Hollow Earth

So, in 1913 he privately published a small book titled

Journey to

the Earth's Interior. The fact that it was privately

published tells us that he was pretty much a crank. If anyone

had taken him seriously, he would have been commercially published.

Still, he shared with Symmes the quality of obsession. He refused

to let it go and in fact became quite furious when anyone challenged his

notion, he was given to bouts of self pity, denouncing conventional scientists

and comparing himself to Galileo. Seven years later, he issued

a revised version of his book, expanded to 456 pages.

Gardner's great contribution was that he was sensible

enough to ditch all those concentric spheres and just stick with a hollow

earth. That made sense, all that evidence marshaled by Americaus

and McBride went towards showing that the world was hollow, not that there

was another world nested inside it.

According to Gardner, the Earth was hollow, it was a shell

800 miles thick, with 1400 mile openings at each pole. Inside,

there was a sun, 600 miles in diameter, giving life and heat perpetually

to the inner world. Other planets were built the same way, the Martian

ice caps were evidence that Mars was hollow. By this time, of course,

there had actually been several expeditions to the North Pole and the South

Pole. Gardner worked hard to argue that they never actually

made it. Apart from that, he was pretty much making the same sorts

of arguments as his predecessors.

And here we finally have Pellucidar.

The inner world of Burroughs has taken its classic form, though arguably.

We have an inner world, polar openings and an inner sun. We

even have prehistoric animals as represented by Mammoths and Woolly Rhinos.

The hypothetical inner world was a mysterious place, a mighty land filled

with lush vegetation and great animals extinct upon the outer world (24

hour sunlight), peopled with savages and mystical cities.

Now, let's be perfectly fair here. Gardner

was a crackpot from day one. He was a crank. He was a lunatic.

Nobody who knew anything took his claims seriously, and in fact, even before

he propounded them, the proof was overwhelming that he was wrong.

Hell, people had already been to the poles. The inner world

theories of Symmes from 1818 to 1878 and Gardner from 1885 to 1926 were

stuff and nonsense from the very start. They were equivalent of the

various junk sciences of today, whether it be scientology, new age mysticism,

crystal healing or ancient astronauts.

That said, they made fertile territory for fiction writers.

Is it any kind of coincidence that Burroughs wrote his first Pellucidar

novel only a year after Gardner self-published his book? Probably

not, though I'm not aware of any proof that Burroughs had obtained the

Gardner book. Still, he could have heard a lecture, read a magazine

article. It's pretty much a given.

You see, the thing is, adventure writers sort of needed

a Pellucidar. The world was filling in fast. Africa had

been the dark continent, but back in 1910 you could throw open a map and

find it thoroughly coloured in by the European powers. The

middle east, the orient, all these places were still mysterious, but no

longer as mysterious as they had been. The world was getting

pretty thoroughly explored, and with that exploration, the opportunities

for adventure writers narrowed.

Mars and Venus emerged, of course, as a source for adventure

stories. These were worlds well known and described, with their

own particular narratives. An inner world represented a brand

new place to have adventures. And it had its own narrative, it was

the inverted world, a place that was a mirror image of ours in some way

or the other, except inside out. Sometimes this amounted to social

satire, with reversed English/American societies skewered, sometimes it

was a womb-like primeval jungle land, the opposite of our own civilized

land. Based on the theories of the origin of frozen Woolly

Mammoths or Woolly Rhinos, the inner world was seen as a sanctuary of creatures

now vanished from Earth's surface.

Thus, the journey to the inner world became a minor but

recurring pulp staple, along the lines of planet and lost race stories.

It seemed to have a minor revival with the Nazis in Germany.

Hitler created the SS, which became a receptacle for Hitler's own occult

and pseudoscientific obsessions. The Nazis

seem to have been fertile ground for crackpots of all sorts, from bizarre

and futile racial theories, to strange notions of astronomy (they believed

that there had been six previous moons

all made of ice), and they flirted with the inner world theory, even

going so far, as some

Indeed, the notion of an inner world didn't quite die

away in the minds of crackpots. It seems to have survived into

the '40s and '50s, promoted by guys like Ray Palmer and talked up by Richard

Shaver. Shaver by the way, was not a Pellucidar enthusiast,

he believed in an underground race, but they lived in caverns, tunnels

and underground cities.

It morphed in bizarre ways. There was a theory,

for instance, that flying saucers were not from outer space, but inner

space. A hyper-advanced race from the inside of our hollow

world were flying around with saucers from the poles. Flying

Saucers were big in the fifties.

Another

theory held that the defeated

Nazis had fled to the inner world through the Antarctic hole and were

even now planning to burst forth onto the outer world. This

had at least the cachet of fitting in with the Nazi's own lunatic notions.

The theory also explained that the flying saucers of the '50s were actually

Nazi

vehicles from the inner world. Personally, if the Nazis had flying

saucers, I don't see why or how they lost. One peculiarity

of this theory is that the Nazi's entered the inner world through the south

pole, rather than the north pole. Basically, Hitler and his

bunch fled across the Atlantic in 'cargo submarines' (no such thing), stopped

off in Argentina for a while, then headed through Antarctica.

There's a fevered compelling logic to this bit of lunacy.

Another

theory held that the defeated

Nazis had fled to the inner world through the Antarctic hole and were

even now planning to burst forth onto the outer world. This

had at least the cachet of fitting in with the Nazi's own lunatic notions.

The theory also explained that the flying saucers of the '50s were actually

Nazi

vehicles from the inner world. Personally, if the Nazis had flying

saucers, I don't see why or how they lost. One peculiarity

of this theory is that the Nazi's entered the inner world through the south

pole, rather than the north pole. Basically, Hitler and his

bunch fled across the Atlantic in 'cargo submarines' (no such thing), stopped

off in Argentina for a while, then headed through Antarctica.

There's a fevered compelling logic to this bit of lunacy.

Yet another theory had Shambhalla, the nonexistent mystical

city formerly attributed to Tibet, located in an inner world filled with

Gurus and Swamis. Its very new agey and therefore not as much

fun as ‘flying-saucer-riding Nazis from the earth's core.’

Of course, by the '60s the theory was on its last legs.

It survived only by cross pollination with other wacky fringe theories.

Cranks and Crackpots had more exciting fish to fry, whether it was invading

saucers, gray aliens, evil doers, communist infiltrators, ancient astronauts

and many other delusionary structures.

And of course, it made for good fiction...

Inner

World Fictions, Before ERB

For

this section, I owe a great debt of gratitude to Richard Lupoff, and his

book, Edgar Rice Burroughs: Master of Adventure and David

Critchfield, and his "Von

Horst’s Pellucidar Website" (both of which I highly recommend)

who between them chronicle most of the pre-ERB and for that matter, most

of the post-ERB inner worlds. Rather than plagiarizing them

too much, I'll confine myself to chronological mentions and where possible,

quote their descriptions of the various inner world stories, and how closely

they line up to Pellucidar.

For

this section, I owe a great debt of gratitude to Richard Lupoff, and his

book, Edgar Rice Burroughs: Master of Adventure and David

Critchfield, and his "Von

Horst’s Pellucidar Website" (both of which I highly recommend)

who between them chronicle most of the pre-ERB and for that matter, most

of the post-ERB inner worlds. Rather than plagiarizing them

too much, I'll confine myself to chronological mentions and where possible,

quote their descriptions of the various inner world stories, and how closely

they line up to Pellucidar.

As a general comment, 'Inner World' novels and stories

have a long history, pre-Burroughs. Mostly, they seem to be subjects

of social and political satire or utopianism, these were essentially 'Gulliver'

stories, where travelers encountered strange and remarkable races which

were in turn, satiric comments on the society of our world.

They seemed to experience a remarkable flowering between

1880 and 1910. Why? Because, by this time, the world

was pretty thoroughly explored. There were still places to

go and things to see, like the source of the Nile. But by this time,

no one was expecting to find a race of dog headed humans in Abyssinia,

or a race of stork necked people in central Asia, nor even the Asian Christian

kingdom of Prester John. Thomas Jefferson might have believed that

mammoths or giant sloths were to be found in the American interior, but

by 1880, everyone knew different. There was simply no room on settled

Earth for extraordinary races and animals. On the other hand, the

world inside earth was unknown territory, a blank slate, completely ready

for Gulliver-esque travels and travails.

However, over time, we can see the evolution of ideas

which were either borrowed from or contributed to the pseudoscience, and

which indeed found their way into Burroughs' Pellucidar.

Pellucidar Map by Edgar Rice Burroughs

Among these notions were that the underworld was inhabited

by strange races of men, by prehistoric animals extinct on the surface,

that it had an inner sun, and even inner moons, that it featured wild seas,

underground passages and polar openings.

When Burroughs came along, the genre was arguably dying

out in favour of more lively and less complex stories. Burroughs

arguably redefined the genre as adventure stories, and redefined the inner

world as Pellucidar.

It might be entertaining to see how many of the pre- and

post-ERB inner world societies could comfortably be fitted into Pellucidar,

but alas, for the most part, I simply don't have a detailed knowledge of

the bulk of these stories.

Pre-ERB Pellucidars

1741 Journey to the World Under-Ground,

Ludvig Baron von Holberg - Nils Klim falls through a hole in the

earth into an inner world. On the inside are a sun and planets.

(Lupoff/Critchfield)

1786 The Adventures of Baron Munchausen

R.A. Raspe - The Baron goes just about everywhere, so of course, he pops

through a hole in the earth to china and back. (Lupoff)

1788 Icosamero by Giacomo Casanova — “Ship-wrecked

siblings are dragged by currents to an underwater crevice, through layers

of water and gas until they emerge in an unknown land. Protocosmo is a

gigantic island floating on a muddy substance at the center of the earth.

It has a sun which gives out pale pink light. It is full of kingdoms and

cities. The people, called Megamicroes, live in underground houses. They

are hermaphrodites and oviparous. The fauna of Protocosmo is similar to

Europe except for the flying horses.” (Critchfield)

1820 Symzonia, Adam Seaborn (probably Symmes himself)

- A sea vessels enters the inner world through the south polar hole and

finds two suns and two moons, which Lupoff suggests are reflections through

the poles. Other accounts of the story have the place lit by

mirrors reflecting polar light. Everything is white, people speak

a musical language, and surface worlders are descendants of Symzonians.

(Lupoff/Critchfield)

1833, 1835, 1838 Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym,MS

Found in a Bottle, and Hans Pfall all by Edgar Allen Poe,

feature hints of an inner world, according to Lupoff. Though its

not actually seen. (Lupoff)

1864 Journey to the Center of the Earth

by Jules Verne, is sort of a hybrid. The Journey seems to pass

through an immense cave system, but it touches on an inner realm so vast

it literally has its own sea and weather system, a giant caveman is spotted,

as well as mammoths on land and sea monsters in the ocean.

The scientific ‘proofs’ which begin the journey point to a hollow earth.

But ultimately, the idea is too ridiculous even in the 1860s, and Verne

soft peddles his way back to an adventure through caverns.

1871 The Coming Race by Edward Bulwer-Lytton

--another deep cave system story, a utopia inhabited by an highly-evolved

race. Yes, it's the “dark and stormy night” guy. (Critchfield)

1880 Mizora by Mary E.

Bradley Lane – “in this world, males are no longer necessary.”

Written by an early feminist, apparently. (Critchfield)

1882 Pantaletta by Mrs. J. Wood

– “the inner world is run by an arrogant woman.” Another early feminists?

1885 The Third World - A Tale of Love and

Strange Adventure by Henry Clay Fairman — “an opening at the

North Pole leads to an inner world “ (Critchfield)

1888 Under the Auroras by William

J. Shaw (Critchfield)

1892 Al Modad by M. Louise

Moore (Critchfield)

1892 The Goddess of Atvatabar by William

R. Bradshaw. The protagonists enter through a polar opening, there

they find an advanced race which rides to war on 40 foot mechanical ostriches.

(Lupoff/Critchfield)

1893 Baron Trump's Marvelous Underground Journey

by Ingersoll Lockwood (1893)---illustrated by Charles Howard Johnson. “An

opening in arctic Russia conveys Trump into the interior world. He passes

through the strange countries of the Transparent Folk, the Rattlebrains,

and others. This lost race story is satirical and intended for adults as

well as children.” (Critchfield)

1894 From Earth's Centre by Bryon Welcome.

(Critchfield)

1895 Dreams of Earth and Sky

by Konstantin Tsiolkovsky. (Critchfield)

1895 Etidorpha by John Uri Lloyd.

A sort of pilgrim’s progress through the underworld. (Lupoff/Critchfield)

1895 Beyond the Paleocrystic Sea

by A. S. Morton. (Critchfield)

1897 In the World Below by Fred

Thorpe (Critchfield)

1898 Through the Earth by Clement

Fezandie – “highly illustrated, strange forces at the center

of the earth (~237 pages) “ (Critchfield)

1898 The Great Stone of Sardis by Frank R. Stockton.

Not really an inner world novel. It features a digging machine which

gets to the center of the earth and discovers a gigantic diamond, the Great

Stone. (Lupoff)

1899 The Secret of the Earth by Charles Willing

Beal, featured polar openings and an airplane trip to the inner world.

The Wright brothers would have been impressed. (Lupoff/Critchfield)

1900 “Nequa” by Jack Adams.

(Critchfield)

1901 Beyond the Great South Wall:

The Secret of the Antarctic by Frank Savile – “An expedition

to the Antarctic in search of lost treasures of the Mayans. The explorers

encounter Cay, a dinosaur worshipped by the Mayans. Illustrations by Robert

L. Mason. (~322 pages)” (Critchfield)

1903 The Land of the Central Sun by

Park Winthrop. (Critchfield)

1903 The Daughter of the Dawn

by William Reginald Hodder - “the Maori are a prehistoric race

in an inner world below New Zealand.” (Critchfield)

1904 Mr Oseba's Last Discovery

by George W. Bell - “the cover illustration is a globe

with a sailing ship coming from the polar opening.” (Critchfield)

1904 My Bride From Another World by

Rev. E.C.Atkins - “nudism & vegetarianism” (Critchfield)

1905 The Sunless City J.E. Preston Muddock

- see the case study, at the bottom.

1906 The Wolf-Men by Frank Powell

(Critchfield)

1908 The Smokey God by Willis George Emerson can

be found online, but it's a painful read, sporting an appalling combination

of sincerity and turgidity.

1908 Five Thousand Miles Underground by Edward

Stratemeyer writing as Roy Rockwood (Roy Rockwood was a house name, and

was also used for the Bomba the Jungle Boy series, as well as for adventure

stories to Mars and the Moon, all of them pretty sub-par and unreadable.

Several of ‘Rockwood’s adventures, including this one, can be found on

the net, however.

1915 The Earthomotor and Other Stories

by Dr.C.E. Linton (Critchfield)

Post ERB Pellucidars

1924 Plutonia by Vladimir Obruchev.

An inner world, prehistoric beasts. Lupoff makes a case that At the

Earth's Core might be the true inspiration, and that this is a Pellucidar

novel. But Rockwood or Verne could also be inspirations.

1927 Drome by John Martin Leahy.

An inner world, hideous monsters, a wicked priest, a beautiful princess

and apparently, absolutely terrible writing.

1929 The Radio Flyers and “The Radio Gun Runners”

Ralph Milne Farley. Pellucidar through and through.

1931 Tam, Son of the Tiger by Otis Adelbert

Kline - Actually, this seems to be an immense cave system under Burma,

a sort of mini-Pellucidar, which is inhabited by Blue, Thark-like, four

armed giant warriors and prehistoric animals. In the context

of a Burroughs/Kline shared universe, this would probably be a sort of

‘Hoos’ bubble, an opening between inner and outer worlds which has covered

over into its own little world.

1935 The Inner World by A. Hyatt Verill.

Possibly Lupoff’s candidate for worst ever.

1935 The Secret People by John Beynon Harris.

Actually, its just an immense cave system under the Sahara occupied by

albino negro dwarfs, and not actually an inner world per se.

1937 Hidden World (In Caverns Below) Stanton A.

Koblentz. An inner world, two warring advanced

nations.

Finally, although this is well beyond the pulp era, a

note should be provided for John Eric Holmes Mahars of Pellucidar

published

in 1976. There's also a lively trade in Pellucidar pastiches

and fanfics.

That

said, the notion of a hollow earth is mostly discredited and worthless

in science fiction these days. Oddly, there are still pseudo-Pellucidars

in the form of immense cavern systems. The most recent underworld

novels have featured immense, hemisphere spanning cave systems, most notably

1999's The Descent which featured an immense cave system ranging

literally across the world, with outlets to the surface everywhere from

the Himalayas to Kansas, underground seas, a lost race of neolithic savages

with psychic abilities and strange animals; and 2002's Underland

by Mick Farren, which mixed Nazis, Vampires and a lost race of Jurassic

Reptiles in a series of gigantic caverns which ran from the north pole

to Antarctica.

That

said, the notion of a hollow earth is mostly discredited and worthless

in science fiction these days. Oddly, there are still pseudo-Pellucidars

in the form of immense cavern systems. The most recent underworld

novels have featured immense, hemisphere spanning cave systems, most notably

1999's The Descent which featured an immense cave system ranging

literally across the world, with outlets to the surface everywhere from

the Himalayas to Kansas, underground seas, a lost race of neolithic savages

with psychic abilities and strange animals; and 2002's Underland

by Mick Farren, which mixed Nazis, Vampires and a lost race of Jurassic

Reptiles in a series of gigantic caverns which ran from the north pole

to Antarctica.

Many of the post-Erb Pellucidars were influenced or shaped

by Burroughs own Pellucidar. While Burroughs drew on predecessors,

once he started writing, he probably occupied the field.

There were a couple of reasons. First, Burroughs simply wrote

more Inner World novels and stories. In total, he did seven Pellucidar

novels, counting serializations in magazines, and then reprintings in book

form, these novels represented not only a pretty big block, but they were

also showing up very frequently in different mediums, and so occupied a

fair chunk of the landscape. Simply by sheer mass, they threw

a long shadow, much as Barsoom's volume throws a long shadow over Mars.

Moreover, Burroughs' Pellucidar novels had a couple of

additional reasons for dominating the landscape. Tarzan

at the Earth's Core combined Pellucidar with his most famous franchise,

arguably injecting a lot of interest in his Pellucidar series and raising

the profile further. Finally, and this can be harsh, but Burroughs'

Pellucidar novels were just better written and a lot more readable and

exciting than other inner world novels. That's cruel, but go and

look up The Smoking God or

5000 Miles Underground and you'll

see what I mean.

Hence, it seems reasonable to assume that many of the

inner world novels or stories that come out after Pellucidar are defined

by Pellucidar, to the point where in the case of Farley's two stories,

you could fit them right in there. Or they may be defined by

their conscious attempt to oppose or do things differently than Burroughs

Pellucidar novels.

Ultimately, the inherent implausibility and ridiculousness

of the subject matter killed off the genre. However, there are still

mutterings of pseudoscience, and even recent novels and movies about immense

cave systems and strange ecologies.

The

Sunless City - a Pellucidar Case Study

Professor

Flintabetti Flonatin becomes intrigued with an mysterious and apparently

bottomless lake in the Rocky Mountains. He decides to try and plumb

its depths with a mechanical fish, a submarine.

Professor

Flintabetti Flonatin becomes intrigued with an mysterious and apparently

bottomless lake in the Rocky Mountains. He decides to try and plumb

its depths with a mechanical fish, a submarine.

With his submarine, he dives down, down and further down,

eventually coming upon a strange land where gold is everywhere to be found.

He goes gold mad, filling his pockets and eventually succumbing to fatigue.

When he wakes, he is in a very strange place.

He is in a hall filled with strange people who look a little like monkeys

and have tails of varying length. They want to know who he is, and

why he's weighed down with useless worthless gold. Flin Flon

is almost in trouble, but the Princess of the realm is struck with love

and intercedes for him.

Thereafter, he becomes embroiled in a battle between two

court advisors. He becomes a tourist in this strange society.

The people of the city, who are refined and civilized, and have a society

where females are in charge, are opposed by an neighboring nation, their

opposites in every way. Flin Flon, being a stranger, is put

on trial for his very life. Eventually, he starts a revolutionary

movement to liberate the oppressed males. From there, he escapes

back to the surface with his remarkable story.

Sounds like classic Burroughs doesn't it?

Well, yes and no. Flin Flon, rather than being a typical Burroughs

hero is a middle aged, balding guy with warts, he's passive taking almost

no action and content to mostly be a spectator. The beautiful princess

who falls in love with him is actually a boot, she's horse faced, and about

as demure as a tavern brawl.

There's very little adventure, and way too many lengthy

conversations which are exercises in absurd style. This is

what passed for humour and wit at the turn of the 19th century.

And its not subtle humour. The land is called Esnesnon, the

princess's name is Yombot, the king is named gubmuh, the dueling savants

are Professor Ytidrusba and the learned Loofmot and Doctor Yrekcauq and

the lawyer is Hturtehteraps. Spell them all backwards and you

get an idea of the level of wit. What this really is, is a

Gulliver's Travel type satire.

Flin Flon comes upon a land of Monkey Men that consider

him primitive, they believe that their inferior souls wind up as tailless

beings on the surface, they value tin and consider gold trash, their women

are sexually aggressive and socially dominant, and so forth.

And all of these things, of course, they consider natural and right, and

explain at length to Flin Flon what a deluded freak he is, and how intrinsically

unimportant and backwards all his science and civilization is.

The inner world is a distorted mirror of the outer one.

That said, the trappings of this inner world, and this

story are all Burroughsian through and through, which sort of leaves us

with the uncomfortable feeling that Burroughs stories have lived backwards.

They were spoofed as trite cliches before they caught on. Thus,

the dashing hero is an old curmudgeon, the beautiful princess is ugly,

etc., her affection for Flin Flon is unrewarded, there are dueling cities

but that never comes into play.

Oddly you could fit this into Pellucidar.

The tailed Esnesnon people seem clear relatives of Burroughs' three races

of Pal-Ul-Don and his two races of Pellucidar prehensile-tailed men.

Though their tails are not apparently prehensile, these people follow the

practice of tail bobbing for social status, thus the highest ranking have

the longest tails and the lowest ranking have short tails.

There is a mention of prehistoric beasts, though this is mostly offscreen,

as is the dueling city. There's no visible sun, but rather

luminous clouds, so in Pellucidarean terms, its likely that the Esnesnon

and their rivals probably occupy one of Burroughs ubiquitous hidden valleys

with a permanent cloud cover.

Of course, its unlikely that Burroughs got his long tailed

monkey men from here. He could come up with it independently easily

enough. But the overall similarity or compatibility of the

setting and overall plot with Burroughs is remarkable. It shows

us that, as with Mars and Venus, a lot of the basic ideas or structure

of Pellucidar were lying around waiting to be had. In a sense,

Pellucidar existed as a fictional landscape before Burroughs wandered onto

the scene and made it his.

There's a small postscript to the story of the Sunless

City. Prospectors in northern Manitoba were looking for minerals,

and found a lucrative strike in some rugged territory. Now

these were guys who were living out in the bush for months on end, and

reading materials were shorthanded. Somehow, a copy of the Sunless

City wound up there, perhaps left behind by a passing traveler or trader,

and got read and passed around until it was dog eared. When

the prospectors found their big strike, one of the pits reminded them of

the Sunless City, so they named the area, and the town that grew up around

the strike "Flin Flon" after the hero of the story. Today,

the story is a minor bit of folklore in Canada, the town of Flin Flon has

several monuments to its fictional forbear, and the town museum sells copies

of the book, which is where I found it.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()