Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute and Weekly Webzine Site

Since 1996 ~ Over 15,000 Web Pages in Archive

Master of Imaginative Fantasy Adventure

Creator of Tarzan and "Grandfather of American Science Fiction"

Presents

Volume 1433

THE BURROUGHS BOOM OF THE '60s

In 1961, a lady librarian in California took a Tarzan book off the shelf on the spoilsport grounds that Tarzan and Jane were living together out of wedlock. She could have had no inkling of the consequences of her misguided act. The furore it aroused in newspapers has brought the Ape Man roaring back out of literary limbo to delight millions of nostalgic Americans and thrown a bomb into the paperback book business.

TARZAN OF THE PAPERBACKS Two years ago, a lady librarian in California took a Tarzan book off the shelf on the spoilsport grounds that Tarzan and Jane were living together out of wedlock. She could have had no inkling of the consequences of her misguided act. The furore it aroused in newspapers has brought the Ape Man roaring back out of literary limbo to delight millions of nostalgic Americans and thrown a bomb into the paperback book business.

By Paul Mandel

LIFE Magazine ~ November 29, 1963The Tarzan books, along with other works of their author, Edgar Rice Burroughs, are runaway best-sellers today and have been ever since they began to come out last year. They have sold something more than 10 million copies, almost one thirtieth the total annual sales of all paperbacks in the U.S. Their resurgence has outraged some publishers whose pet books have been rudely elbowed off the display racks, but has brought a gush of renewed nostalgia to at least two generations who remember and revel in the days of Burroughs' first triumphs and are delighted to see them recur.

From 1914 until roughly 1940 Burroughs was a splendid phenomenon in publishing. His books, the first one of which appeared exactly 50 years ago next June, sold 35 million copies in the face of concerted critical antagonism which called them (in one typical example) "flap doodle... wild, utterly preposterous, utterly meaningless and humorless... long-winded and repetitious... sheer bumble puppy." Burroughs owed most of his success to one creation -- a little English orphan lord who was raised and educated by apes: Tarzan.

Burroughs wrote 24 Tarzan books in all and they were translated into 31 languages, including Esperanto, Urdu and Russian (the Soviets felt that although Tarzan was a peer, he had been brought up by proletarian apes so it was all right for young Communists to like him). In Germany after World War I, Tarzan's sales were so vast that a disgruntled local publisher printed a counter-Tarzan tract called Tarzan Eats Germans.

In the U.S. the novels inspired Tarzan bread, Tarzan sweaters, Tarzan ice cream, 37 Tarzan movies, and innumerable do-it-yourself Tarzans: one day during the time of Tarzan's greatest success there were l5 children in Kansas City hospitals who had hurt themselves falling out of trees while playing Ape Man.

The original Tarzan hard covers fathered a vast tribe of derivative publications. There were Tarzan Big Little Books and Better Little Books, which were small and chunky like baby bricks, and Tarzan Big Big Books, which were the same in content but bigger -- roughly the size and consistency of a modern club sandwich. They alternated short, fevered pages of text (Tantor advanced his snake-like trunk toward the terrified Swede. His little eyes blazed. At last he had found the creature who had killed his mate) with snappily captioned drawings (Bellowing Horribly, the Elephant Charged: Brooding, ULP Gazed into the Fire.) There were Tarzan bubble-gum cards and Tarzan cartoon strips, and even an official manual for Tarzan Clans which included a 500-word dictionary, English-Ape and Ape-English.

World War II seemed to end the craze for Tarzan books, perhaps because substantial clans of American boys had started living their own real-life jungle dramas. By the time Burroughs died in 1950, leaving his valuable rights to his books to his three children in Tarzana Calif. Tarzan appeared to have entered the literary dinosaur park reserved for other has-beens like the Boy Allies or Don Sturdy.

Then came the lady librarian in California. When newspapers heard what she had done, they published reams of foolish speculation about just what Tarzan and Jane were to each other -- foolish because anyone who had studied the Ape Man's domestic arrangements knew that Jane's father, an ordained minister, had married the two in a small family ceremony in the bush. In any case, all the publicity apparently started old Burroughs fans rooting around for more books to buy for their children and reread themselves. They found to their dismay that only nine of the the 24 Tarzan books were still in print, on the backlist of a New York publisher named Grosset & Dunlap.

The sales of these nine titles increased 25%, but they by no means satisfied the pent-up interest the librarian had unwittingly released. Other publishers petitioned the Burroughs estate for permission to reprint Tarzan. Perhaps because they were content with the revenues from their movie rights, the heirs failed to answer most of these inquiries. Finally one dogged Tarzanophile publisher wrote the Library of Congress to see exactly what rights the heirs still owned. The library's answer disclosed that Burroughs' heirs had committed a lapse which would have sent Burroughs' hero skulking into the underbrush. U.S. copyrights expire in 28 years unless renewed, and the heirs had forgotten to renew the copyrights on at least eight Tarzan books plus about 20 other Burroughs novels. Lo, the Ape Man lay naked in the public domain.

There ensued, starting to the spring of 1962, a feast over his literary body as savage as any jungle episode Burroughs ever created. (At the smell of blood the panther gave forth a shrill scream, and a moment later... beasts were feeding side by side upon the tender meat.) New York Canaveral Press got out 19 hardback Burroughses. Dover issued four paperbacks combining 10 Tarzan paperbacks. Ballantine published 10 Tarzan paperbacks, then two more, plus nine non-Tarzan books, and now plans to bring out another 10 Tarzans and one more non-Tarzan. The threat of a mass freeload on what they had previously regarded as their patrimony sent the Burroughs' heirs to shaking out the drawers and safes at Tarzana to see if there might be anything left which they did own. They found at least five unpublished novels and promptly sold hardcover rights to Canaveral for these and any of the books which were still copyrighted. By next summer some 70 Burroughs novels will be in print.

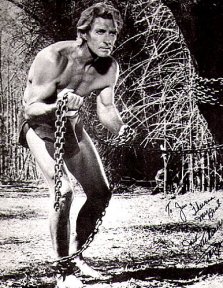

In the illustrations for their reprints the publishers have shown wide differences of opinions about what Tarzan looks like. Ace's Tarzan -- in the tradition of the big Little, Big Big and Burroughs' original books -- is mesomorphic, equipped to wrestle monsters and save maidens from parboiling. Ballantine's Tarzan is sleek and cerebral-looking. But whatever their image of the hero, all the books have been selling wondrously. Both Ace and Ballantine have gone into enormous second printings -- 300,000 and 110,000 per title respectively. In the Ace catalogue today Edgar Rice Burroughs occupies an entire separate category, a little smaller than either Science Fiction or Mysteries, but larger than Adventure, Humor or Self-Help.

Not everybody is delighted by this Burroughs rebirth. Norman Podhoretz, the editor of a furrowed-brow magazine called Commentary, has ticked of Burroughs' style as "that Victorian kind of heaviness." And Dr. Fredric Wertham, an extremely serious student of the psychiatric implications of modern publishing trends, feels that there is something sick about Tarzan's return. "The vogue," he says, "has a definite social meaning: to bring out acceptance of violence crime and war -- as a legitimate means of social action. Tarzan appeals to the easiest thing to appeal to: our primitive instincts. We have to try to get out of this."

On the other hand there has been a countercurrent of delight. The Wall Street Journal, which often confines its scrutiny of books on such sprightly topics as corporate merger, gave Tarzan a whole column not long ago. "When it comes to forming the mind," the writer asked, "would you rather have... Tarzan... or the modern comic books [or] Spillane...? The Tarzan stories... are among the most elevated and edifying books... now on the racks."

The Wall Street Journal has found some noisy support for its enthusiasm in the activities of a recently formed organization called the Burroughs Bibliophiles, which has nearly l,000 members. It publishes a Burroughs fan magazine and a newsletter and holds a yearly "Dum-Dum" which is ape talk for "meeting," at which it gloats over its favorite author's renaissance.

And there are indeed some things to gloat over. The first is that Burroughs' non-Tarzan novels -- he wrote 36 of them -- turn out to be better than the Tarzan books. Some are even good. They range from Upton Sinclair-like examinations of gamy corners of American Life (The Mucker and The Girl from Hollywood) to inventive science-fiction books. These included 10 Mars novels, all of which will shortly be out on paperback, about an earthman named John Carter, who finds himself on Barsoom, the local name for Mars. The planet is populated by a colorful assortment of white apes green Communists and nubile red girls. Carter marries one of the latter -- no question either.

There are six topsy-turvy novels about a world called Pellucidar inside the earth's core. It is first found when the controls on a big man-carrying drill becomes stuck at Full Down. Pellucidar's rulers are a nasty lot of reptiles. Just once Burroughs lets down the barriers between his two sets of books and has Tarzan visit Pellucidar. The Ape Man gets in some good licks for the mammals upstairs. Some of the non-Tarzan books are taut and serious and the best one, The Lost Continent, formerly called Beyond Thirty, tells of a war-ruined England peopled by savages who call it Grabritin. It sounds much more like Orwell than Omtag the Giraffe.

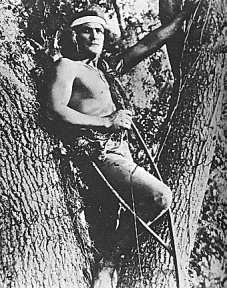

The second lesson from the Burroughs revival is that his book Tarzan is far more interesting than the movie one. The films presumably had trouble finding suitably muscled ape men who could learn long lines, so their Tarzans tended to be laconic ("Me Tarzan. You Jane. Where Boy?") The book Tarzan, on the other hand, is always saying things like "I know the legend well, and because it is so persistent and... circumstantial, I have thought that I should like to investigate it." This makes him a lot more sophisticated, if a little long-winded.

Until the most recent movies the film Tarzan tended to be a treebody keeping pretty close to home with Jane, while the book Tarzan tuns out to be a veritable boulevardier, visiting such exotic locals as Paris, London, the Dutch Indies, Baltimore and Wisconsin, in the course of his effort in behalf of the apes at home. Lest any heretic dispute the superiority of the book Tarzan over the Hollywood Tarzan, he should read one of the newly reprinted paperbacks Tarzan and the Lion Man. In its last chapter Tarzan visits Hollywood incognito. He is offered a chance to play the lead in a Tarzan movie but flunks the screen test and loses out to an adagio dancer.

The apes in the Tarzan series came strictly from Burroughs' imagination.

In size and habitat -- such as eating meat - they are unlike any apes in the world.

Cover art and publishing information for all the ERB novels

-- including the "Sixties Boom" editions mentioned in this article --

is featured in the ERBzine C.H.A.S.E.R. Illustrated Bibliography at:

www.ERBzine.com/chaser

MEANWHILE, BACK IN THE TREETOPS . . .

By Margaret Ronan

Practical English Magazine May 8, 1964Ed. Note: Knowledgeable readers might be interested in comparing the similarities between this article and the previous Life Magazine piece. You might also keep track of the numerous errors contained here.

What's that whooshing through the trees overhead? Is it a bird? Is it a monkey? Is it Superman? No, it's only Lord Greystroke (sic), better known to most people as Tarzan of the Apes.The jungle-dwelling Tarzan, raised and educated by friendly apes after a plane crash killed his parents, is one of the most popular fictional characters ever created. He made his first swing into the public consciousness in 1912, when Edgar Rice Burroughs wrote Tarzan of the Apes and sold it as a serial to All-Story Publications. Readers swung to Tarzan so enthusiastically that Burroughs was kept busy for years afterward, turning out Tarzan novels by the dozens. Through the years, these books have sold over 32 million copies and have been printed in 58 languages and dialects, including Esperanto, Tamil, Urdu, and Russian. Even though he is technically a member of the English peerage, Tarzan is a favorite behind the Iron Curtain. The Soviets seem to feel that his adoption by apes makes him a true proletarian.

Although Burroughs died in 1950, Tarzan is as lively as ever. Books about him keep right on selling at the rate of 50,000 a year. Tarzan buffs rejoiced when an unpublished Tarzan story was discovered among Burroughs' papers. Entitled Tarzan and the Madman, it tells of a pilot who develops amnesia after crash-landing in the jungle. Having mislaid his own identity, the pilot decides he must be Tarzan! Does the real Tarzan resent this pretender? Not at all. Instead, the kindly ape man tries to protect the pilot from the dangerous consequences of his delusion -- such as falling out of trees.

HAPPY TARZAN DAY!

Tarzan has also been the hero of radio serials and comic strips. There have been Tarzan sweaters, Tarzan bubble-gum cards, Tarzan ice cream, and Tarzan bread. During a "Tarzan Day" in Kansas City, Missouri, 15 children were taken to the hospital with broken bones, incurred by falling out of trees while imitating the jungle gymnast. There's even a Tarzan fan club. It's called the Burroughs Bibliophiles, and boasts a thousand members, most of them adults. Many of the Bibliophiles have written their own Tarzan stories for fun, and others have made maps of Africa to show where Tarzan's adventures took place. They also hold a yearly "Dum-Dum" (ape talk for "meeting"). For those to whom Tarzan-talk is pure Greek, there's an official Tarzan Clan manual, including a 500-word dictionary with English-Ape and Ape-English sections.

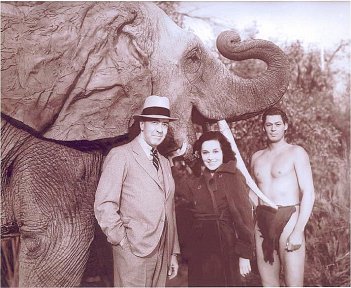

Almost as popular on the screen as they are in books, Tarzan's adventures have been the subject of 30-odd films, with actors of all shapes, sizes, and vocal ranges. The first actor to play Tarzan was Elmo Lincoln, who made a hulking, beetle-browed appearance onscreen in 1919. He swung about on the jungle vines draped in wolf skins. Although there are no wolves in African jungles, Lincoln's costume was true to the spirit of Burroughs, who knew next to nothing about Africa. What little he did know he had gotten from a once-over-lightly reading of In Darkest Africa, by Henry Stanley, the American newspaperman who found missionary David Livingstone in Central Africa in 1871.

Perhaps the most famous movie Tarzan was swimming champion Johnny Weissmuller, who starred as the ape man in a dozen films from 1932 to 1946. The Tarzan that Burroughs wrote about was highly vocal, given to making such statements as "I do not interfere among tribes beyond the borders of my own country unless they commit some depredations against my people." As played by Weissmuller, Tarzan spoke haltingly in simple fragments -- "Me Tarzan. You Jane." Weissmuller left his most enduring mark on the character of Tarzan when he emitted the bloodcurdling Tarzan yell, "Eh-wa-au-wa-aoooow!" When moviegoers heard that screech, they knew that Tarzan was on the way to rescue some maiden in distress, or to save his friends, the wild animals, from evil white hunters.

Johnny Weissmuller could take only partial credit for the Tarzan yell, however. Blended on the sound track were four other sounds, including a hyena's howl played backward.

The current movie Tarzan is Jock Mahoney, an ex-Marine fighter pilot and former movie stunt man. Mahoney plays Tarzan as a well-educated Englishman who just happens to live in a treehouse. His interpretation is closer to the character drawn by Burroughs than Johnny Weissmuller's inarticulate strongman.

EVOLUTION OF A FAILURE

What is the cause of Tarzan's popularity? Do readers like to identify with superheroes who triumph over evil and subdue nature by using only their own strength and wits? Are Tarzan's adventures popular because they are a form of "escape" in which the reader can lose himself, forgetting the responsibilities and problems of real life?Whatever the secret of Tarzan's success, it certainly doesn't lie in any literary genius on Burroughs' part. His style was often clumsy and laborious, and his sentences frequently ran almost nonstop. Here is a sample from Tarzan Triumphant: "That a tragedy so remote should seriously affect the lives and destinies of an English aviatrix and an American professor of geology, neither of whom was conscious of the existence of the other at the time this narrative begins -- when it does begin, which is not yet, since Paul of Tarsus is merely by way of prologue -- may seem remarkable to us, but not to Fate, who has patiently been waiting these nearly two thousand years for these very events I am about to chronicle."

Norman Podhortz, editor of Commentary, describes Burroughs' style as "that Victorian kind of heaviness"; and the magazine Commonweal rates his literary standing as "somewhat below Rider Haggard and somewhat above Trader Horn." However, Burroughs does have his supporters. Although Alva Johnston wrote that his work had a "galloping commonplaceness as one of its assets," he also paid tribute to Burroughs' undoubted talent for plot and narrative by adding that "the pages of his books have the authentic flash and sting of story-telling genius."

Perhaps the most surprising pat on the back comes from The Wall Street Journal. In a whole column devoted to the ape man, the Journal asks: "When it comes to forming the mind, would you rather have Tarzan or modern comic books? The Tarzan stories are among the most elevated and edifying books now on the racks."

Of course The Wall Street Journal is referring to Tarzan's moral code, not Burroughs' style, when it uses the words elevated and edifying. Tarzan is sort of a jungle Lone Ranger, busy righting wrongs, saving wild animals, and swinging to the rescue of imperiled tourists. One such tourist is Jane, whom Tarzan meets while she is traveling in Africa with her father. Tarzan and Jane are latter (sic) married by her father, an ordained minister, and live happily almost ever after in a treehouse. Their son Jack (known simply as "Boy" in Tarzan films) has grown up in the course of Tarzan novels, gone away, and married. Tarzan and Jane are now grandparents, but you would never guess it to see them swinging on those vines.

Oddly enough, Burroughs took up writing only after he had failed at almost everything else. At 37 he had been fired from jobs as a cattle drover, railroad policeman, law clerk, door-to-door salesman, and stenographer. Several businesses he started ended in bankruptcy -- including a correspondence course for young men determined to learn how to succeed!

As Burroughs' fortunes slid steadily downhill, he turned for comfort to telling himself fantastic stories about heroes who never failed. Eventually, he began to write out his fantasies -- and to his astonishment publishers bought them as fast as he wrote them. Although an elementary rule for would-be writers is to write about things they know about, Burroughs specialized in writing about things he knew noting about. He blithely put tigers in his imaginary African jungle, although there are no tigers in Africa. The apes he described were much bigger than real apes, and they subsisted on an unapelike diet of raw meat. Burroughs' novels were so popular that many Americans grew up sharing his odd ideas about the flora and fauna of Africa.

Tarzan is undeniably a "superman" character, but some of the feats Burroughs had him accomplish were super-suerhuman. For example, Tarzan finds some discarded books at an abandoned camp site. He can speak only the language of apes up to this point, yet he uses the books to teach himself to read and speak perfect English!

EVOLUTION OF A CHARACTER

Although most Tarzan films keep Tarzan confined to the jungle, Burroughs managed to turn his hero into quite a globe-trotter in several later novels. While campaigning for governmental protection of wild animals, Tarzan visits London, Paris, and the United States. He never takes off for outer space, but he does make a side trip to the center of the earth. In Tarzan and the Lion Men, he even goes to Hollywood to try out for the lead in a Tarzan film. He doesn't get the job because the director says he's "not the type."Edgar Rice Burroughs died in 1950 at the age of 75. Even if future generations ignore his books, his Tarzan will probably enjoy linguistic immortality. According to Webster's Third New International Dictionary, a tarzan (common noun) is "a strong, agile person of heroic proportions and bearing." Burroughs also put Tarzan on the map by founding the incorporated city of Tarzana, in California. The creation of Tarzana was a publicity stunt; but the founders of Tarzan, Texas, weren't interested in publicity. They simply wanted to honor their favorite hero.

APES AND MARTIANS

Poul Anderson

Boys Life ~ September 1972Tarzan of the Apes "lived as the lion lives -- a true jungle creature dependent solely on his own prowess and his wits, playing a lone hand against creation." Seldom armed with more than a knife and lasso, seldom protected by more than a loincloth, he met head-on every imaginable menace. From Numa the lion, through cannibal tribesmen and the scheming pagan priests of lost cities, to the might of a European empire -- the ape-man triumphed over all his enemies.

Yet the author who dreamed him into being was hardly anything like his jungle hero.

Edgar Rice Burroughs was a man with a sense of humor and proportion. He never pretended he was great. He stumbled into his lifework, after spending his young manhood in failure and frustration. He had little style nor even much grammar. The literary classics left him cold, so he learned nothing from them. The "factual" background of his stories was sometimes wildly wrong. He acknowledged all this. Yet his name flew around the world. And now, after a period of eclipse, it is again being widely seen.

Tarzan is as familiar a figure, as much a prat of modern folklore, as Sherlock Holmes. Another Burroughs character, John Carter of Mars, also enjoys reborn popularity even though Mariner probes have shown that Mars cannot possibly be the kind of place the stories describe. Likewise, we know today that the Earth cannot be hollow, with a tiny sun at the core lighting up an inhabited inner world; but the "Pellucidar" tales are eagerly read. These three series are only part of the Burroughs revival.

Meanwhile, many contemporaries of his, honored authors of serious and significant books, are forgotten.

But let's not put down Edgar Rice Burroughs. He had two great virtues that outweigh many faults. First he owned an extraordinarily rich imagination. Second, he was a born teller of fast-paced, action-crammed stories. Either of these gifts is hard to come by. The combination is unbeatable. It may not produce great literature, but what it does produce is fun to read.

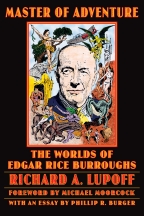

New Reprint EditionsHis fans are by no means children only . Among them are distinguished adults, some of whom have formed an organization, the "Burroughs Bibliophiles," with hundreds of members. Lightheartedly, it names its meetings after the ape gatherings in the Tarzan yarns -- Dum-Dums -- but also does scholarly research. A number of articles on Burroughs have appeared in respectable magazines. So have a biography, The Big Swingers, by Robert W. Fenton (republished by George McWhorter of the Burroughs Memorial Collection at the University of Louisville in 2003), an excellent book-length survey of the writings themselves, Edgar Rice Burroughs: Master of Adventure by Richard M. Lupoff.

Let us follow these authorities in a quick treetop swing through their chosen country.

We begin with Burroughs, who was born in Chicago, in 1875. He recalled, with humorless horror, that because of a diphtheria epidemic his parents put him for a while in the safer environment of a private school for girls! When he was 14, for similar reasons they sent him to a ranch they owned in Idaho. There he spent some happy months as a junior cowboy. he learned to ride "anything that wears hair," as he put it, and started developing a powerful physique.

Later he flunked out of one military school, but did so well in another that it was a hard shock when, at age 20, he failed an examination for West Point. Undaunted, he enlisted as a private in the cavalry. But the Indian troubles were practically over and Army life in the Arizona desert proved dull. Young Burroughs may not have been greatly disappointed at being discharged after less than a year's service. The reason given him was that he had a weak heart. Nevertheless, that heart was to beat for a total three-quarters of a century.

During the Spanish-American War, he tried to join Theodore Roosevelt's Rough Riders but was refused. The story goes that he also was denied a commission in the Chinese army, but almost got one from Nicaragua. A storekeeping stint in Idaho also led nowhere, except that it gave him time to do his first real writing -- some charming, witty verses for his small niece -- never published. In 1900 he returned to Chicago, went to work for his father's storage battery company, and married his childhood sweetheart.

The business was hard hit by the national panic of 1901 but Burroughs had never been happy in it anyway. Three years later he quit to try his luck in the gold fields of the West. Unsuccessful here, too, he became a policeman. By 1906 he was back in Chicago, where he spent the next half-dozen years in a variety of minor positions with different companies. None was particularly interesting or rewarding and the coming of children strained the meager family finances.

It is no wonder that Burroughs consoled himself with vivid daydreams. He had no thought of making them public until after he became the advertising manager for a small pharmaceutical house. This forced him to read the pulp magazines that carried the advertisements. He decided that not even he could write as badly as some of their published authors. So in 1911 he submitted his first novel to All-Story.

He did this in secret because, as he later said, "I was sort of ashamed of writing as an occupation for a big, strong, healthy man." The pen name he chose was modest, Normal Bean, meaning an ordinary head. By mistake, the first part was printed as "Norman" when the tale appeared the next year.

It was Under the Moons of Mars, which led off the John Carter series. In it, the hero escapes from besieging Indians by a kind of astral projection. Suddenly he finds himself on the red planet. It turns out to be a wildly romantic world, where barbarian swordsmen range through the ruins of a once-great civilization and across the dry bottoms of vanished seas.

Already the author showed how he could imagine in detail. There is a whole Martian ecology. The natives are divided not only into different tribes and kingdoms, but into distinct cultures, and even separate species. Each kind has its own language and folkways. Such fascinating peculiarities add much color to the story.

Though John Carter was to have a long career, his original adventures drew little attention. The payment did encourage Burroughs to continue writing, in longhand on the backs of old letters. Several fantastic stories quickly sold. They included Tarzan of the Apes.

Even this, Burroughs' most famous work today, did not succeed overnight. Though it was serialized, not until 1914 did a publisher agree to issue it in book form. By then Burroughs had become a full-time writer. Tarzan caught the public fancy and soon made him wealthy.

The whole world knows the basic story. Marooned and finally dying on the coast of West Africa, the English Lord and Lady Greystoke leave a baby son. A she-ape, who has just lost her own young, adopts the infant. He grows up among her kind, learning to speak their simple language and that of other jungle animals. Between his aristocratic heritage, and the strength and agility needed for survival in the wild, Tarzan becomes a virtual superman. At last he meets his own sort, learns civilized ways, and -- in The Return of Tarzan -- marries Jane Porter, an American. But he is never really happy in cities, and they settle down in Africa. From that home base, Tarzan goes on to countless unlikely adventures.

Flaws are many. The phrasing is often crude. Racial stereotypes are common. (However, almost all writers of that period used them, and Burroughs does picture Tarzan's black friends, the Waziri as an admirable people.) No such breed of apes ever existed as were supposed to have raised the hero. In the magazine version of the first story, he fights a tiger. Readers wrote in to protest that there are no tigers in Africa. One loyal South African declared that the name was locally given to leopards. Nevertheless, Burroughs changed the animal before the book was printed. On the whole, he admitted, he wrote best about subjects of which he was ignorant. He himself never set foot in Africa.

His strong points stand forth just as clearly. Tarzan, for instance is not the vine-swinging simpleton of the comic strips and movie serials. In the novels, he is a complicated, almost Hamlet-like character. He speaks several human languages and knows all about modern machinery. He and Jane do not live in a treetop hut, but in a large house on a well-managed plantation. Though he enjoys getting back to wilderness life now and then, he never dreams of spending his life among the apes.

Burroughs had much more humor than he is usually given credit for. Thus, he disliked gold, and makes one of his characters define it as "a mental disorder." In another book, Tarzan visits Hollywood and is turned down for the movie role of Tarzan!

This writer did not confine himself to fantasies, either. He also did historical fiction, here-and-now adventure, and Westerns. The adventures include two hard-hitting exposes of corruption in the real world. The Westerns include a pair of novels about the downfall of the Apaches, movingly sympathetic to the Indians.

Middle-aged and a family man, Burroughs reluctantly stayed out of military service in the first World War. But he did produce a good deal of patriotic propaganda. In one of these works, Tarzan gives a German armed force such a hard time that, for years afterward, no German publisher would touch the ape-man. When the Nazis came to power, they banned him altogether.

Meanwhile, in 1919, Burroughs had moved to southern California. There he acquired a large ranch and mansion, not unlike Tarzan's spread. The general area came to be known as Tarzana, and still is. There is also a Tarzan, Tex.) For years he lived a happy and productive life. He wrote prodigiously, no longer in pencil but with typewriter and dictaphone. Between movies, radio, comics, toys, ornaments, a boys' club, and translations into some 30 foreign languages, Tarzan became a thriving industry.

His popularity extended to the Soviet Union, whose leaders deplored the fact that their people would rather have such "bourgeois escapism" than "socialist realism."

The problems of filming Tarzan are more amusing to read about than they have been to cope with. His famous battle call was developed by combining several different sound tracks, such as a human yell, a hyena howl run backward, and a violin's G-string. Actors learned to imitate it. Animal actors can be more temperamental, like the herd of hippos that got loose and ate up local crops to the tune of $25,000. But the series still goes on. As of today, 14 different men have had the title role.

Burroughs himself lived well in those Hollywood years. He was especially fond of horses and motor cars. Otherwise, though, his tastes were simple. But by 1934, hard days had come again. When the Depression hit him financially, his business manager showed him he must cut back. In 1938 he sold his ranch and moved to Hawaii.

There he continued writing; at the same time, in California, some of his books still were being filmed. But the second World War had come, and it drew the attention of people -- Burroughs among them -- to more important things.

He took the war with great seriousness; and it finally gave him to see action. He wrote patriotic columns for a local paper in Hawaii, hitched his way to Tarawa and Kwajalein to view the fighting first-hand, and rode along on some bombing missions. The sight of flak bursting around the plane did not seem to bother him. He was a celebrity, who counted generals and admirals among his readers. But he sought out enlisted men whenever he could, and became well-liked by them. Back in Honolulu, he was active in civil defense.

Afterward he returned to California, hoping to live in Tarzana. But his enterprises were in financial trouble and housing was scarce and expensive. He had to settle for a cottage nearby. There he lived and worked on, never losing his zest for life until failing health handicapped him. In 1950, while reading the Sunday comics in bed, he died of a swift heart attack.

For a decade or so, it looked as if his books would die, too. Now they are vigorously back among us, and they may well go on for a long time, because they reflect the vitality and enthusiasm of their author. Once, when designing a fictional solar system, Edgar Rice Burroughs wrote to an astronomer who had helped with some technical details: "I am glad that you found fun in answering my queries. I find fun in the imaginings which prompt them; and I can appreciate, in a small way, the swell time God had in creating the universe."

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

BILL

HILLMAN

Visit

our thousands of other sites at:

BILL

AND SUE-ON HILLMAN ECLECTIC STUDIO

ERB

Text, ERB Images and Tarzan® are ©Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.-

All Rights Reserved.

All

Original Work ©1996-2006/2020 by Bill Hillman and/or Contributing

Authors/Owners

No

part of this web site may be reproduced without permission from the respective

owners.