(a).

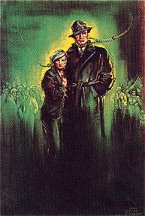

This book was written shortly after Burroughs posed for the famous picture

of himself standing on the rock above the sea in Santa Monica in 1916.

This book was written shortly after Burroughs posed for the famous picture

of himself standing on the rock above the sea in Santa Monica in 1916.

Let's take a moment to put these titles into

perspective with Burroughs' career. Let's try to identify some of

the changes he's going through. It is safe to assume that in 1911

at 36 years of age when he sat down to write A

Princess Of Mars he was in a state of terror that life had

passed him by, that he had failed the big test. If he says that he

considered writing to be an unmanly occupation then he was desperately

grasping at the last straw. If he failed as a writer than he would

have had an excuse as it was a sissy occupation but he still would have

been psychologically destroyed.

But Princess sold and then too did Tarzan

Of The Apes. Buoyed by these successes he continued to write

achieving during the year 1913 a pinnacle of success achieved by few writers.

Most importantly Burroughs could for the first time in his adult life perceive

himself as a somebody, as the man he always thought he was, or could be.

The miracle of 1913 continued and with the

confidence of a seemingly inexhaustible pen promised to continue.

Burroughs indulged his whims during those fantastic years between 1913

and 1916. He apparently bought everything that he had ever wanted.

When he left on that fabled drive from Chicago to LA, in addition to a

car, a truck and a driver he had 2 1/2 tons of, pardon the expression,

junk.

He was living in a dream. I envision

the surreal picture of this caravan pulling to the side of the road away

out there on the road to anywhere with Burroughs pitching his white and

blue striped circus tent while the kids aged about eight, seven and three

cranked up the record player. They didn't need electricity in those

days, you wound a record player up. Then as the horn blared out 'Are

You From Dixie' singing lustily the family danced in the moonlight.

Place that picture against a rising full moon.

Imagine a country rube happening along on Old

Dobbin to see such a scene. It's just like Toad and his caravan from

Wind

In The Willows isn't it? What memories the children must

have had.

And all the time Burroughs' personality was unraveling

as he metamorphosed into a new persona.

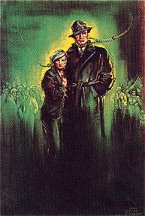

Let's take a look at that picture by the seashore

closely. It is revealing. There is no reason not to believe

that this picture was carefully thought out and posed by ERB.

The photo is frequently cropped so as to put Burroughs in the center but

in its uncropped state the sea stretches far to left making the subjects

of the photo both ERB and the feminine sea. Burroughs is standing

on the right on a rock high above the water. Let us believe that

was his intent. In 'Somewhere

Out There' written from January to March 1916 the theme is the poem

by H.H. Knibbs also

titled 'Out There Somewhere'

in which the dream lover is waiting in the South by the sea. Obviously

ERB has an idea fixed in his mind.

As he finished the novel he tramped South to

the sea. Thus the sea, the waters of the subconscious, the fructifying

water of the female represents both the destructive and constructive aspects

of the female. Standing on the rock, as opposed to the shifting sands,

high above the waters represents Burroughs' hopeful reunion with his Anima.

Burroughs' persona itself, his Animus is equally

interesting. He is very expensively dressed. That overcoat

is a very new one, either a Kuppenheimer or a Hart, Shaffner and Marx,

as Burroughs combines the two names in a reference in Bridge

And The Kid. It is also unnecessary in California at any

time of the year. His shoes are shined, top quality also. His

hat is pulled low over his face as he stands above the photographer looking

down on him or her with wry, bemused hint of a smile with he endows his

creations. His hands are in his coat pockets with the thumbs exposed.

Thumbs are a sexual symbol of potency, as in 'under my thumb' so he is

feeling confident in his success if not cocky. He is the Mysterious

Stranger. The Shadow. He is at the very height of his success

and yet facing the problems his success has brought. This photo represents

the high summer of his life. It is never going to be this good again.

'Out there Somewhere' pointed to a resolution

of his psychological problems while Bridge And The Kid apparently resolved

them, for the moment.

There is an interesting numerical relationship

in Burroughs' visits to the coast. His first was in 1913, this second

visit was in 1916 and he would move permanently to California in 1919-

three year intervals. One wonders at what point in his life he began

his California dreaming.

Thus Burroughs began Bridge

And The Kid in a state of exhilaration. It took him nearly

six months to finish it which for him was a long time.

His period of extreme fecundity was also over.

In the future he would be driven to work because he needed the money but

his psychological release was finished with these two novels.

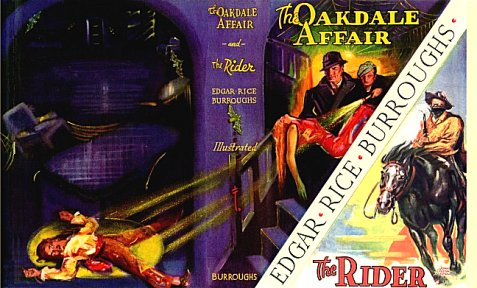

(b).

Bridge

And The Oskaloosa Kid is one of Burroughs most finely crafted novels.

It is extremely rich in content. Because of the apparent ease with

which Burroughs writes one disregards the components of the tale and there

are many in what I consider his most detailed and intriguing novel.

ERB began the hobo theme in Vol. I of this trilogy

The

Mucker, developed it in the sequel Out

There Somewhere and continues it not only in the character of Bridge

and the Kid but in the criminal gang and throughout the novel.

The hobo obviously intrigued ERB and why not? rather than just discuss

the hobo theme as elements of the story let's look more closely into the

subject.

Just as today the so-called homeless occupy

an amazing amount of social attention so in Burroughs' time the hobo was

an inescapable phenomenon. He was ubiquitous, he was everywhere as

a reading of 'Out There Somewhere' and 'Bridge And The Oskaloosa

Kid' indicate. Burroughs found the hobo fascinating and even to a

degree identified with him.

Every town of any size had a Main Stem on which

the Hoboes congregated. Chicago itself with most rail lines converging

on it from all directions was the Main Stem of hoboism while Madison was

the Main Stem of Chicago. As it chances the offices of the American

Battery Company were on Madison Street thus the young Burroughs would have

had plenty of opportunity to observe and study the Hobo.

As a yard policeman in Salt Lake City in 1904

he would have had further opportunity to familiarize himself with the species.

His first writing effort- Minidoka-

in 1908 or so gives the Hobo a prominent place actually siting Chicago

as the Hobo capital of the country.

In both these novels he gives a very unflattering

picture of the Hobo. In both novels the Hoboes figure as criminals,

even murderous criminals. In Bridge And The Kid they are responsible

for the crime wave in normally placid Oakdale.

When the Kid stumbles into the lair of six

hoboes all are willing to rob her while an actual coldblooded attempt on

her life was made by Dopey Charlie.

Burroughs associates one, the General, with

Coxey's Army of 1894. Eighteen ninety-three was the beginning of

a severe depression perhaps equal to the depression of the thirties.

In 1994 Jacob Coxey organized a march on Washington of the unemployed seeking

relief. The host was known as Coxey's Army.

Burroughs who was frequently unemployed and

hard up yet always found jobs to scrape by, exhibited all the pride of

the resourceful by condemning the 'soldiers' of Coxey's Army as bums who

wouldn't work, hence the General had never held a job and never would.

He preferred to rob and kill rather than work.

One of the more memorable episodes of the book

is when morning dawns on Jeb Case's farm and the hoboes come streaming

out of the barn and haystacks as Case takes up a shotgun to make sure they

move on.

Burroughs who had no use for the IWW, the Industrial

Workers Of The World or Wobblies, introduces them also in the character

of the Sky Pilot. As the Wobblies were composed almost entirely of

the hobo class they might easily have been classed as hoboes pure and simple.

The Sky Pilot is I believe based on Big Bill Haywood of the Western Federation

Of Miners, the WFM, and then when he was expelled from that organization,

of the IWW.

Big Bill is one of the great figures of the era and he

figures indirectly in the history of the Burroughs Boys so ERB would have

concentrated on his career. The battles of the hard rock miners in

Colorado, Idaho and the West in general with the mine owners were ferocious.

The resistance to their just demands by the mine owners forms one of the

most disgraceful episodes in American history.

Big Bill was at the center of the dispute.

In Idaho the governor who resisted the WFM was Frank Steunenberg. He had

appointed Harry and George Burroughs as delegates to a mining conference

so that the Burroughs had an association with him.

When Steunenberg left the governor's chair

in 1905 he was blown to bits by a bomb placed in his mailbox. Big

Bill didn't place the bomb but it does seem likely that he planned the

bombing. ERB thought so. In one of the most famous trials of

the era Haywood was defended by Clarence Darrow who somehow got him off.

Thus Burroughs describes the Sky Pilot as the

man who planned the crimes but was always somewhere else when they were

committed. He made people 'disappear' in the manner in which Steunenberg

disappeared.

From the WFM Big Bill went on to be the leader

of the Wobblies. There can be no doubt that Burroughs was opposed

to the Wobblies. In book after book in this period he denounces the

outfit. After the Great War broke out in 1914 the IWW became especially

active leading to the speculation that their activities were funded by

the Kaiser's gold. This was never proven at the time but it seems

very probable as the Germans wanted to disrupt American productivity while

Big Bill and the Wobblies wanted to take over industry and the government

on behalf of the 'working man.' The crime wave of Oakdale caused

by the hoboes may have been a fictionalization of a wave of IWW activity

which resulted in a large number of violent strikes in 1916 shortly before

the book was written. Thus Burroughs wove Big Bill Haywood, Coxey's

Army, The Western Federation Of Miners and the '16 Wobbly actions into

the story in a 'highly fictionalized' manner.

In fact Burroughs may have been recapitulating

several decades of labor history as he introduces the great Chicago detective,

Burton. Obviously based, on one level, on Allan Pinkerton of the

famous Pinkerton Detective Agency which was employed to control labor unrest.

In fact the Pinkertons had kidnapped Big Bill as operatives against the

WFM turning him over to Idaho after Steunenberg was murdered. One

of their operatives, Charlie Siringo, was instrumental in breaking up the

miners in the Coeur D'Alene area. Wonderful story he tells in 'A

Cowboy Detective'.

Not only does Burton represent the Pinkertons

but after withholding his first name throughout the story, as an inside

joke, Bridge who knows Burton hails him as Dick. Of course slang

for detective was a 'dick' as in Dick Tracy but also Dick is short for

Richard. So Burton was Richard Burton. Richard Francis Burton

was the famous African explorer so Burroughs weaves in another historical

reference.

By the time the book was finished on 6/12/17

the United States was involved in the war with Germany so at that point

the activities of the IWW were treasonous.

(c).

Burroughs' novels are always more complex than they

seem on the surface. Like any novelist he has to have a story to

tell but that story arises from conscious and subconscious motives.

Some of the conscious motives are in the relation of his disguised feelings

about unskilled labor, the hoboes and the IWW. The subconscious motives

emerge in his depiction of his heroine, Abigail Prim and the hero, the

Happy Hobo, Bridge. As this is an Anima/Animus story it should be

clear that Abigail Prim represents ERB's Anima and Bridge represents his

Animus. The two characters are not original to this story but a variation

on all his heroines and heroes whose adventures are a variation of the

adventures of all his heroes and heroines.

Burroughs entered the hobo theme in the first

volume of this trilogy The Mucker then developed the theme in the

middle volume 'Out There Somewhere' which introduces his stellar character

Bridge, the Happy Hobo.

As it chances one of Burroughs' literary heroes

was Jack London.

London (1876-1916) was an exact contemporary, Burroughs being born in September,

London in the following January. He was actually born eleven days

after Emma.

It has been suggested that the death of London

in 1916 influenced Burroughs' writing of 'Out There Somewhere'.

As the book was written between January and March and London died in November

of that year the connection seems unlikely.

It does seem likely that Burroughs read everything

he came across of London's. He seems to have thought he knew enough

about London's life to write a biography of him. If he was that familiar

with London that is an interesting detail. It is impossible to know

for certain what he read of London's as there are no London titles in the

library

as published here on the ERBzine. While ERB seems to have made

little attempt to fill in his library with titles that he read before he

came into money it would seem likely that between 1913 and 1916 he would

have picked up some London titles.

London was a very prolific writer penning dozens

of novels, some few volumes of non-fiction and hundreds of short stories

that appeared in dozens of magazines. It would seem highly improbable

that Burroughs would have read everything.

While London made a circuit of the United States

and Canada in 1894 as a knight of the road not a great deal of his hobo

writing had made it to print by 1916. The most significant of his

hobo writing was a volume titled The

Road of 1908. It would seem probable that Burroughs read

at least this if he associated London with the road.

Perhaps more importantly London was uppermost

in his mind in 1916 since W.R. Hearst had hired London to cover the Mexican

Revolution in 1914. Bridge is introduced in 'Out There Somewhere'

on his way to Mexico. So that if Bridge is to be associated with

London his dispatches from Mexico were probably the immediate reason.

Even though Burroughs admired London as a writer they were at

opposite poles politically. London claimed to be a confirmed socialist

although he doesn't write like one. As a revolutionist which he claimed

to be he was in opposition to ERB.

Their views of the hobo were also in opposition

so one wonders exactly what Burroughs was thinking. Burroughs makes

Bridge the only honest hobo on the road while all others are depicted as

violent criminals. In the first hobo scene in 'Out There Somewhere'

Bridge and Byrne are accosted by murderous hoboes who are defeated by the

pugilist Byrne. The whole cast of hoboes in Bridge And The Kid

are

hardened criminals of the first water.

London on the other hand apologizes for his

hoboes. When not victims of society they are philosophers who can

astonish college professors with their learning. Thus London tends

to whitewash the criminal aspects of the hobo. So, the question might

arise as to whether Burroughs was correcting the image presented by his

hero attempting to give him his take on the tribe. Remember London

was still alive when 'Out There Somewhere' was written and published in

magazine form. It could have been meant for his eyes.

London was only eighteen when he made his tour

of the country. He had already shipped out on a tour of the orient

when seventeen. His moniker was Sailor Jack. He enlisted as

a recruit in a clone of Coxey's Army know as Kelly's Army which left for

DC from California.

As Burroughs mentions Coxey's Army in Bridge

And The Kid while he associates the Army with the IWW, then Wobbly

activities may have called to mind London's hobo experience. Obviously

all of these elements are interconnected.

If George

McWhorter of the BB and Philip

Berger are right and the L. In L.Bridge refers to London Bridge that

would be in keeping with the punning on the name Dick Burton.

London could be an element in the character

of Bridge but not necessarily the dominant one while Byrne would also represent

London. It seems clear that Burroughs had been fascinated by the

character of the hobo from an early age. As noted, the hobo appears

as a significant character in his very first attempt at writing, Minidoka.

Burroughs may have affectionately joined his

persona with that of London as Bridge is a declassed aristocrat which is

almost a necessity for a Burroughs hero. In this case Bridge is a

'Virginian', a natural gentleman as well as a cultivated one. The

Virginian in American history is the antitheses of the Puritan.

The Virginian was thought to be an innate gentleman,

one of the 'quality' as opposed to the 'equality'. The prototype

of the manly man. Nearly all of Burroughs' heroes are Virginians.

Jack London didn't have that distinction so in my opinion he represented

Burroughs in his declassed state.

As a Virginia gentleman Bridge, apparently

an unconventional sort, 'volunteered' to be a hobo because he rejected

the settled life but he can reenter the aristocracy at will as he does

at the end of the book. Hence while all other 'boes are criminals

or at least suspect Bridge is honest and above board. He's known

far and wide to the authorities as the only honest hobo. He's the

hobo who has Burton's confidence.

In 'Out There Somewhere' he is in search

of the woman of his dreams. In Bridge And The Kid he finds

her.

'She' is obviously Abigail Prim. Gail is a

Cinderella figure. Her mother died. Jonas Prim, her father,

remarried. Her stepmother, Pudgy Prim, while not conventionally wicked

nevertheless does not wish the best for her step-daughter.

As the story opens, this is kind of hard to

follow, Pudgy has sent her daughter to live with the man she has chosen

as Gail's future husband to see if she couldn't learn to like him a little

better. I'm sure I must have missed a connection somewhere but that's

the way I read it.

The man Pudgy has chosen for her is more than

twice Gail's nineteen years with the attendant infirmities. ERB doesn't

tell us how old Gail was when her mother died but it seems strange that

he father wouldn't do more than grumble about this odd plan of his second

wife.

While Gail appears to accept her step-mother's

decision to the extent of getting on a train bound for her suitor's town

she gets off early returning to Oakdale where she disguises herself as

a boy then burgles her own property to take up a life on the road as a

hobo. Of course ERB conceals from us that the girl Gail and the boy

burglar are one and the same.

Having looted herself of a fairly good sized

fortune, a necklace alone was appraised by the General, a Hobo, at fifty

thousand dollars while she was carrying at least two thick wads of bills

worth thousands as mixed in with the greenbacks, few of which are ones,

were many yellow backs. There's some currency information for you.

Researching currency on the web it appears that yellow backs were hundred

dollar bills while other denominations were all greenbacks. Completing

the burglary she heads on down the road as night falls. After a couple

misadventures with a dog and a bull Gail falls in with six criminal 'boes

in an abandoned shed.

A true innocent she flashes her fortune in

front of the startled eyes of the 'boes, hardened criminals all.

Mocking her naivte one of the 'boes claims to know her as the Oskaloosa

Kid who is out robbing and murdering at that very moment. Gail doesn't

know this, misses the joke and assumes the character of the Oskaloosa Kid.

After a failed robbery attempt by the 'boes

Gail runs down the road in a gathering storm with the hoboes in pursuit.

As she comes to a fork in the road she encounters the Happy Hobo Bridge,

apparently oblivious to the gathering storm, who is merrily tramping along

reciting some of his favorite poetry- out loud. The meter comes through

better that way although the practice might raise comment from casual observers.

Bridge and the Kid join destinies.

So what is Burroughs talking about here in the psychological sense.

He is following the same scheme he follows in all his Anima stories.

Usually a sudden storm takes place on a yacht at sea and the survivors

find themselves on a desert island. The plot develops that ERB used

in the Outlaw Of Torn

also. In that plot the little Prince's nurse was murdered by a fencing

instructor who then dressed as a woman to serve as the little Prince's

Anima. The Prince in Outlaw

Of Torn was torn from his secure position in the world as Burroughs

was in his.

So what is Burroughs talking about here in the psychological sense.

He is following the same scheme he follows in all his Anima stories.

Usually a sudden storm takes place on a yacht at sea and the survivors

find themselves on a desert island. The plot develops that ERB used

in the Outlaw Of Torn

also. In that plot the little Prince's nurse was murdered by a fencing

instructor who then dressed as a woman to serve as the little Prince's

Anima. The Prince in Outlaw

Of Torn was torn from his secure position in the world as Burroughs

was in his.

In this story Gail has a wicked step-mother

who wants to marry her off to an undesirable man. Gail voluntarily

dresses and poses as a boy so that fencing master and boy serve the same

function with the roles reversed so that Gail is prepared to reveal herself

and assume the role of Burroughs' Anima in female form.

In 'Outlaw' the Prince who becomes the outlaw, or outcast,

Norman, is torn from his high station where he is declassed as an outlaw.

In this story Bridge voluntarily declasses himself because he 'prefers'

a life on the road.

This book was written four years after Outlaw

so Burroughs psychology has evolved. The emotional problem centers

on Burroughs' confrontation when he was eight or nine years old with a

bully on the way to Brown school. ERB was so terrorized by the incident

that his Animus was emasculated and his Anima was nearly annihilated.

(The fencing master kills the nurse Maud and assumes the identity of the

Anima.) As I have pointed out this means that Burroughs in his terror

was hypnotized into accepting certain beliefs about himself. These

are prime psychological facts which control one's behavior. While

under the influence of the hypnotist (John the Bully in this case) certain

suggestions (Burroughs' interpretation of the terror, his psychotic response)

were implanted in his subconscious. These suggestions then influence

or control the actions of the subject so long as they are active.

They may be exorcised in the course of time, resolved in some manner, or

they may control one's actions for life as improbable as that may seem

to some people.

The purpose of analysis should be to locate

these suggestions and resolve them. Freud attempted this with the

'talking cure.' Burroughs is doing the same thing in his writing,

discussing his fixation (embedded suggestion) from many angles in an attempt

to resolve it, thus freeing himself of its control. All of his writing

from 1911 to this novel contributed to its solution. In the Bridge

Trilogy ERB succeeded in understanding his fixation but apparently lacked

the follow through to eliminate it as a spirit of malaise followed him

through out life.

In meeting his reconstituted Anima in boy's

disguise at the fork in the road or street corner, the crossroads in Outlaw,

the original scene of hypnosis, he has recreated the original hypnotic

incident. The hoboes pursuing Gail represent the bully. Symbolically

they will all be joined in the haunted house during the storm. In

this case the house takes the place of the desert island.

Thus Bridge leaves the broad, well traveled

road of happiness, (the yacht sinks) to join his destiny with the Kid on

the less traveled hazardous road.

They enter the abandoned farm house which represents

Burroughs' self after the confrontation with the bully. Thus ERB's

Animus and Anima are once again together in his self or house although

his Anima is disguised as a male and he doesn't recognize her.

In this unresolved state the real Oskaloosa

Kid drives by. He throws a woman from an open tonneau, in a driving

rain storm no less, firing a shot after her. The shot misses, the

girl is stunned but otherwise uninjured. Thus ERB's previous Anima

is returned to him but unlike Maud she is unconscious but alive.

The three are joined by the dual aspects of the bully spending the

night together during a storm in a room of the farmhouse. So that

is the set and setting.

2.

ERB is accused of being unduly influenced by

his readings. This may be true. As a dependent personality

as a result of his encounter he is highly influenced by those he admires.

He has a high level of suggestibility as a result of his hypnosis.

He seems to have been very willing to accept suggestions from publishers

such as Metcalf of All Story who suggested a medieval story which ERB undertook

against his better judgment in Outlaw Of Torn.

However imitation is the sincerest form of

flattery. ERB was a very flattering sort of guy. In this book

he mentions several influences whose manner he imitates to some degree.

But he always has a very original story.

The first issue is that of why a hobo hero.

The hobo was an unacceptable topic for literature at that time, still is.

In fact Burroughs two hobo novels are rather daring departures from tradition.

There may be a genre of hobo novels, if so these two stories are the bedrock

of the genre. They may have been the first hobo novels published.

They were certainly intended as a tribute to

Jack London. Although Burroughs acknowledges deep respect for London

none of his volumes are found in Burroughs' library. It is also true

that very few volumes from Burroughs poverty years are in the library.

The library seems to consist of childhood books and volumes Burroughs purchased

after he came into money. He doesn't seem to have gone back and picked

up old favorites. In such case we can't know for sure how much or

what of London's Burroughs actually read.

London was prolific writing dozens of novels

and collections of short stories along with some few non-fiction

titles. Among the last was a record of his hoboing experience entitled:

The

Road. Published in 1908 there is a good chance Burroughs

may have read it. An indirect 'proof' might possibly be found in

the sobriquet the Oskaloosa Kid. There is an Oskaloosa in both Kansas

and Iowa. When London took his hobo trip from Oakland across the

US and back by way of Canada in 1894 in part as a member of Kelly's Industrial

Army, he makes mention of incidents in Oskaloosa, Iowa. If Burroughs

read The Road the name Oskaloosa may have stuck in his memory.

London himself had difficulty getting the Road

published as his publishers didn't believe the hobo a suitable subject

for treatment. If London ever intended a hobo novel he never wrote

it. He did author several hobo related short stories. Once

can't be certain which of the short stories Burroughs read if any.

Certainly he couldn't have read them all.

London was also sent to Mexico by the Hearst

papers to cover the Mexican Revolution in 1914 so it is very possible that

as 'Out There Somewhere' deals with the Mexican Revolution

Burroughs may have been more directly inspired by London's Mexican dispatches.

In are event these two volumes are generally

agreed to have a direct reference to Jack London with which conclusion

I have no dispute.

I did discuss the Bridge Trilogy in my Only

A Hobo which elicited the response from fellow writer David Adams

that I should have read London's Martin Eden if I wanted to understand

the Mucker. I had read it. I have read it again. Unfortunately Mr.

Adams failed to refer to the passages that would have enlightened me.

Reinforcing the hobo image of the two books

is Burroughs use of hobo poetry throughout 'Out There Somewhere'

and the first half of Bridge And The Kid. Central to the first

volume is HH Knibbs poem 'Out There Somewhere' after which ERB's story

is named. The theme of that poem most important to Burroughs is that

his dream woman or Anima awaits him in the South down by the sea. Weaving

through these images and through Bridge And The Kid is Service's

'The Road To Anywhere.' It doesn't hurt to be familiar with these

two poems.

If writing a hobo novel was avant garde, building

one work around the work of another writer was no less daring. One

can only say that ERB was fearless.

There is a possibility that Burroughs

may have intended 'Out There Somewhere' as an introduction to both

Knibbs and London. He left for an extended stay in California shortly

after completing the novel during which he may possibly have intended a

trip North to Sonoma to visit London but his favorite author chose the

unpropitious moment to cash in. November 22 is also the death date

of John F. Kennedy and Aldous Huxley although forty-seven years later.

If Jack hadn't been in such a hurry he might easily have made it a three

way termination.

It is noteworthy that Burroughs did extend

an invitation to HH Knibbs who wrote the poem around which the novel was

built and who accepted the invitation.

The hobo theme may also have been suggested

by an increasing feeling of restlessness which resulted in the familial

hoboing across the country after 'Out There Somewhere' was completed in

1916.

Assuming the hobo influences of the IWW, London,

Knibbs and Service it would not seem necessary to look for others but Burroughs

was able to cram more into a hundred fifty pages than any author I have

read. On page one of Bridge And The Kid he mentions Sherlockian which

refers to Conan Doyle, Raffleian which refers to the Raffles of Doyle's

son-in-law E.W. Hornung and the Alienist which refers to psychologists

of some type.

Doyle was an ever present influence on Burroughs.

His admiration for Doyle's detective Sherlock Holmes permeates his work.

He is forever trying to write a good detective story of which 'Bridge And

The Kid' is an excellent example if not the most perfect example of his

Holmesian stories. A great many of his other novels have detective

stories concealed within them.

Bridge And The Kid is one of the best.

I'm sure everyone is able to guess that the Kid is a girl in disguise before

the story ends but the question is how early? I don't know exactly

when I did but by the time the Kid went out to 'rustle grub' his relationship

with Willie Case gave it away for sure. Still, even knowing did not

diminish enjoyment of the rest of the story. Both Bridge and the

Kid are excellent characters as was Burroughs detective, Burton.

Loved all three. Actually I loved all the characters including Beppo

which were all drawn vividly.

One wonders if Burroughs knew that Hornung

was Doyle's son-in-law. If so the union of the two in one story is

clever and piquant. Hornung and Raffles are probably not so well

known now but Raffles was a very popular character for a long time.

Whereas Doyle created the master detective his son-in-law created a mirror

image master thief. Doyle didn't take kindly to Hornung's character,

Arthur J. Raffles, for that was his name. Raffles was a gentleman

thief or 'amateur cracksman' who stole from his hosts on country weekends.

His sidekick was named 'Bunny.' The Kid, Gail in disguise, is of

course a counterpart to Holme's Watson and Raffle's Bunny.

As a further inspiration then we have Holmes

and Watson and Raffles and Bunny for Bridge and the Kid. Pretty amazing,

huh? You can see why Philip Farmer got carried away in Tarzan

Alive.

Then later in the book in a fit of exuberance

Burroughs mentions H. Rider Haggard and Jules Verne although I can't find

references to their work in this story. Just that ERB liked their

stuff.

Finally we have the mention of the Alienist.

This certainly implies that Burroughs took more than a passing interest

in psychology. As wide ranging as his interests were one is forced

to believe that he knew who Freud and Jung were by 1917. What he

knew of their work is open to conjecture although "Tarzan's First Nightmare"

of this period follows Freud's dream theories pretty closely.

I would imagine he knew something of William

James and I am convinced of FWH Myers. Beyond that I can't say.

It seems clear to me that Burroughs is attempting some careful psychological

portrayals in this book.

Having discussed the preliminaries let's see

how Burroughs develops set and setting in this very delightful story of

times, places and landscapes which will never be seen again.

ONLY THE STRONG SURVIVE

Part II

Into The Mysteries

Burroughs does a good job in the Holmesian sense

in this book enclosing mysteries within mysteries. The central mystery

is who is committing the crime wave in Oakdale. Having learned from

his mentor, Conan Doyle, Burroughs skillfully withholds details to enhance

the suspense then disclosing them to reveal the mysteries. The organization

of the scheme of crimes gradually unfolds to show that the real Oskaloosa

Kid is one of the perpetrators. So we have a clever doubling of a

sweet girl posing as the vicious criminal the Oskaloosa Kid.

The girl who was seen with the criminals could

have been Gail since she has disappeared without a trace never having arrived

at her destination. Gail was not the girl seen with Reginald Paynter

who was robbed and murdered and the crooks it was Hettie Penning who was

ejected from the car speeding past the Squibbs place by the real Oskaloosa

Kid.

As indicated Hettie Penning represents the

dead early Anima of Burroughs who has here been resurrected. As in

all cases of Burroughs representations of his failed Anima she appears

to be a 'bad' girl but in reality is merely misunderstood.

Bridge himself is a mystery man and double.

He is a hobo but with great manners and an excellent education. He

is definitely a member of the Might Have Seen Better Days Club. The

real club was organized by Burroughs when he served as an enlisted man

in the Army in 1896.

In this case Bridge is in actuality the son

of a wealthy Virginia aristocrat who has left home because he prefers a

life on the road. In reality Burroughs was declassed at eight or

nine by John the Bully and by his father's subsequent shuffling of him

from school to school finally sending him to a bad boy school which Burroughs

describes as little more than a reformatory for rich kids.

If one looks at his career he was on the move

quite a bit. During his marriage he seldom lived in one house for

more than a year or two then moved on.

Just as Bridge will assume his proper identity

at the end of the novel so through his writing Burroughs has abandoned

the shame of his hard scrabble years from 1905-13. In a sense he

is assuming his proper identity with this novel.

Bridge and the Kid having joined together at

the fork in the road, one is reminded of Yogi Berra's quip: When

you come to a fork in the road, take it. take the less traveled dirt road.

I read word for word frequently dwelling on

the scenes created. Burroughs is a very visual writer. Standing

at the fork in a driving midwest summer lightning, thunder and deluge storm

they can hear the pursuing hoboes shouting down the road. Ahead of

them is a dark unknown and a house haunted by the victims of a sextuple

murder.

Indeed, Burroughs describes almost a descent

into hell, or at least, the hell of the subconscious:

Over a low hill

they followed the muddy road and down into a dark and gloomy ravine.

In a little open space to the right of the road a flash of lightning (followed

one imagines by either the crash or the deep loud rumbling of the thunder)

revealed the outline of a building a hundred yards (that's three hundred

feet, a very large front yard) from the rickety and decaying fence which

bordered the Squibb farm and separated it from the road.

There are those who say Burroughs doesn't write

well but in a short paragraph he has economically drawn a verbal picture

which is quite astonishing in its detail. The house is a hundred

yards from the road. In the rain and muck that might be a walk of

two or three minutes.

A clump of trees

surrounded the house, their shade adding to the utter blackness of the

night.

That's what

one calls inspissating gloom. One might well ask how any shade

can add to utter blackness but one gets the idea. There is some intense

writing thoroughly reminiscent of Poe but nothing like him.

The two had reached the

verandah when Bridge, turning, saw a brilliant light glaring through the

night above the crest of the hill they had just topped in their descent

into the ravine, or, to be more explicit, the small valley, where stood

the crumbling house of the Squibbs. The purr of a rapidly moving

motor car rose above the rain, the light rose, fell, swerved to the right

and to the left.

"'Someone must be in

a hurry." commented Bridge.

There isn't any better writing than that.

Another writer can say it differently but he can't say it better.

Just imagine the movies' Frankenstein or Wolf Man when you're reading it.

Burroughs did as well in less than the time it takes to show it.

A body is thrown from the speeding car a shot

following after it. Bridge goes to pick up the body.

Thus the mystery and horror and terror of the

stormy night has been building. Bridge carrying the body which may

or may not be alive asks the Kid to open the door.

Behind him came

Bridge as the youth entered the dark interior. A half dozen steps

he took when his foot struck against a soft yielding mass. Stumbling

he tried to regain his equilibrium only to drop fully upon the thing beneath

him. One open palm extended to ease his fall, fell upon the uplifted

features of a cold and clammy face.

Yipes! What more do you need? Cold

and dripping, half crazed with fear, overwhelmed by the thought that he

might be a murderer the Kid's hand falls on cold and clammy dead flesh.

He is also aware that the murderous hoboes are hot on his trail.

If that doesn't get you then somehow I think

you can't be got.

Not finished yet Burroughs builds the tension.

Striking a match from the specially lined water proof pocket of Bridge's

coat they find a dead man wearing golden earrings. Obviously a gypsy

but while staring in unsimulated horror they hear from the base of the

stairs of a dark dank cellar the clank of a slowly drawn chain as a heavy

weight makes the stairs creak.

This is too much for the nerves of the Kid.

Burroughs brilliantly contrasts the terror of the unknown in the basement

with the fear of the dark at the top of the stairs. You know where

that's at, I'm sure, I sure do. In a flash the Kid chooses the unknown

at the top of the stairs to the horror in the cellar.

What do you want?

The hoboes are still slipping and sliding down

the descent into the ravine of the subconscious. Horror in front,

terror behind. There is absolutely no place to hide. Nightmare

City, don't you think? How could anyone do it better? What

do you mean he can't write? Put the scenes in a movie and everyone

in the theatre would be covering their eyes. It would be that Beast

With Five Fingers all over again. Maybe worse. Never saw that

one? Check it out. Peter Lorre. Terrifying. Of

course, I was a kid.

The clanking of the chain recreates an incident

in Burroughs' own life when he had a job collecting for an ice company.

He called on a house and while he was waiting he heard the clanking of

a chain coming slowly up the driveway. Waiting with a fair amount

of trepidation he saw a huge dog dragging the chain appear. ERB backing

slowly away forgot about the delinquent ice bill.

In this case the chain is attached to Beppo

the dancing bear but Bridge and the Kid won't know that until the next

day.

They retreat into an upstairs bedroom where

what Burroughs describes in capitalized letters as THE THING and IT pursues

them. I remember two movies one called the Thing and the other IT.

Just when the thing retreats the murderous

gang of hoboes enters the house. Wow! Out of the frying pan and into

the fire in this night of terrors as the lightning continues to flash and

the thunder crash.

Discovering the dead man and as the bear begins

moving again four of the hoboes flee while two who were on the staircase

being trapped in the house flee into the same bedroom as Bridge, the Kid

and the girl. Shortly thereafter a woman's scream pierces the lightning

and thunder then silences as the storm settles into a steady drizzle.

The rest of the night is one tense affair between

the murderous hoboes, Bridge and the girls. Not a moment to catch

your breath.

In the morning when they go downstairs the

mystery increases when they find the dead man gone and nothing in the cellar.

If they'd had Tarzan there he could have smelled whether it was a brown

or a white bear.

After a brief confrontation Dopey Charlie and

the General are driven off. Bridge's relationship with the Kid is

then deepened. Even though all the Kid's reactions are repulsive

to Bridge yet he feels his attraction to the seeming boy growing stronger.

Not since he

had followed the open road with Byrne, had Bridge met one with whom he

might care to "pal" before.

This brings up an interesting hint of latent homosexuality.

My fellow writer, David Adams, has objected that in my analysis of Emasculation

as applied to ERB is that he should have been a homosexual which he wasn't.

There are degrees of emasculation and there

are various degrees of psychotic reaction to it. I don't say and

I don't believe that ERB was a homosexual but there was a degree of ambiguity

introduced into his personality by his emasculation. I have touched

on this in my 'Emasculation, Hermaphroditism and Excretion.'

Here we have another example of it as Bridge

is experiencing some homoerotic emotion which is very confusing to

him as he has never wanted a 'pal' before.

If Burroughs took his 'inside' information

on hoboes from Jack London's The Road then Bridge is the sort of

hobo London describes as the 'profesh', the hobo highest in the hierarchy

of hobodom. London always thought of himself as a quick learner,

so one doesn't have to award his statements too much credibility but Burroughs

apparently took him at face value.

As London describes the 'profesh' he has been

on the road so long that he knows all the ropes. Unlike the unkempt

bums he realizes the importance of a good front and always dresses neatly.

But he is hardened and capable of committing any crime.

While Bridge is obviously intended to be a

'profesh' he is neither a criminal nor does he dress to put up a good front.

Another category of hobo London lists is the

'road kid.' These are young people just starting on the life of the

road. The 'profesh' would often take one or more of these road kids

under his wing as his fag, as the British would say, or in 'Americanese'

a 'pal'. In other words in a homosexual relationship. Thus

this displays ERB's sexual ambiguity which David couldn't locate in my

psychological analysis of ERB's emasculation. In this case the ambiguity

will be resolved and explained when we learn that the Kid is the beautiful

young woman, Abigail Prim and both Bridge and Burroughs heave a sigh of

relief.

Nevertheless ERB is discussing homosexuality

in an open and natural way which may be unique for its times. But

then, remember that one of ERB's hats in this story is that of the Alienist,

so that in these pages we are deep in the psychological abstractions and

Doyle's mystery stories as influences.

Now comes the time for breakfast. Someone

has to 'rustle' grub. We have already learned in 'Out There Somewhere'

that Bridge doesn't rustle food, he rustles rhyme. Nothing has changed.

The Kid goes out to get breakfast and when she comes back with the goods,

true to form Bridge bursts forth with several snatches from H.H. Knibbs

which surprisingly the demure Miss Prim recognizes. What's she been

reading?

How might this apply to Burroughs' own life?

Let's look at it. Burroughs was enamored of How To books but in his

heart he must have considered them a fraud. Willie Case will soon

pick up his copy of How To Be A Detective which he finds completely

unapplicable to his circumstances. He also has the good sense to

throw the book away reverting to his native intelligence which may be a

subtle comment of the topic of How-To books by Burroughs.

ERB always considered himself of the executive

class. After his humiliating experience trying to sell door to door

he never again attempted it. Instead as a master salesman he wrote

sales manuals for others to use as they went door to door selling pencil

sharpeners or whatever while he sat in the office waiting for orders.

Hence in his own life he was the 'rustler of poetry' or manuals while others

rustled grub in the door to door humiliation of the actual selling.

ERB always makes me smile.

In this case in what may be a joke the Kid

just buys the goods from the homeowner reversing the roles.

There are those who insist Burroughs can't

write but I find his stuff wonderfully condensed getting more mileage

out of each word than anyone else I've read. Just see how he describes

breakfast:

Shortly after,

the water coming to a boil, Bridge lowered three eggs into it, glanced

at his watch (an affluent hobo) greased one of the new cleaned stove lids

with a piece of bacon rind and laid out as many strips of bacon as the

lid would accommodate. Instantly the room was filled with the delicious

odor of frying bacon.

"M-m-m-m! gloated the

Oskaloosa Kid. "I wish I had bo- asked for more. My!

but I never smelled anything so good in all my life. Are you going

to boil only three eggs? I could eat a dozen."

"The can'll only hold

three at a time," explained Bridge. "We'll have some boiling while

we are eating these." He borrowed the knife from the girl, who was

slicing and buttering bread with it, and turned the bacon swiftly and deftly

with the point, then he glanced at his watch. "Three minutes are

up." He announced and, with a couple small flat sticks saved for

the purpose from the kindling wood, withdrew the eggs one at a time from

the can.

"But we have no cups!"

exclaimed the Oskaloosa Kid, in sudden despair.

Bridge laughed.

"Knock an end off your egg and the shell will answer in place of a cup.

Got a knife?"

The Kid didn't.

Bridge eyed him quizically. "You must have done most of your burgling

near home," he commented.

The description of the breakfast between the time

Bridge looked at his watch and when the three minutes were up was delightfully

done. I could smell the bacon myself while I especially like the

detail of swiftly and deftly turning the bacon with the knife point.

Nice details aren't they? You'd almost

think Burroughs had actually done things like this for years. There's

enough blank spots in his life that he may have had more experiences of

this sort than we know about. Take for instance the three days in

Michigan between the writing of' Out There Somewhere and Bridge

And The Oskaloosa Kid. He says it took him twelve hours by train

on four different lines to return to Coldwater from Alma. It is not

impossible that he was hoboing back for the experience. He knew that

he was going to write Bridge And The Kid next; might he not have been picking

up local color?

Likewise in 'Bridge And The Kid' he mentions

the road from Berdoo to Barstow with seeming familiarity. Had he

met Knibbs and the two embarked on a few days road trip as the expert Knibbs

showed him some of the ropes?

I don't know but there is something happening

in his life which has not been explained.

Perhaps also the hoboism which appears in 1915-17

in his work when by all rights his success should have permitted him entry

into more exalted social circles symbolized a rejection by so-called polite

society. If so, why? Certainly the serialization of Tarzan

Of The Apes in the Chicago paper must have raised eyebrows when people

said something like: Is that the same Edgar Rice Burroughs who's been tramping

around town for the last several years?

After all people live in a town where a reputation

is attached to them whether earned or not. In reviewing the jobs Burroughs

had after he left Sears, Roebuck there is a certain unsavory character

to them. Indeed, one employer, a patent medicine purveyor was shut

down by the authorities while ERB then formed a partnership with this disgraced

person. Where was Burroughs when the authorities showed up to shut

the business down? I make no moral judgments. I'm of the Pretty

Boy Floyd school of morality: Some will rob you with a six-gun, some

use a fountain pen. Emasculation is the name of the game.

It is certainly true that many, perhaps most,

of the patent medicines of the time were based on alcohol and drugs therefore

either addictive or harmful to the health. Samuel Hopkins Adams was

commissioned by Norman Hapgood of Collier's magazine to write a series

of articles exposing the patent medicine business in 1906. http://www.mtn.org/quack/ephemera/oct7.htm

A consequence of the articles may very well have been the shutting down

of Dr. Stace. I think it remarkable that Burroughs didn't distance

himself from Stace at that time.

Even as Adams was presenting his research on

patent medicines Upton Sinclair was exposing the hazards of the Chicago

meat packing industry whose products were no less hazardous to the public

health than patent medicines. Sinclair's book The

Jungle as well as perhaps Adams' articles resulted in the Pure

Food and Drug Act of 1906.

The products of the meatpackers were so bad

the British wouldn't even feed them to Tommys. That's pretty bad.

So, if the Staces of the world were criminal

and ought to be put out of business then by logic so should have the Armours

and Swifts but what in our day would be multi-billion dollar industries

don't get shut down for the minor offence of damaging the health of millions.

One can't be sure of Burroughs' reasoning but his

writing indicates that he was keenly aware of the hypocrisy of legalities.

Perhaps for that reason he stuck by Dr. Stace.

However Stace was put out of business and the

Armours and Swifts weren't. While I applaud ERB's steadfastness I

deplore his lack of judgment for surely his reputation was tarred with

the same brush as Dr. Stace.

When society figures may have asked who this

Edgar Rice Burroughs was they were given, perhaps, a rundown on Dr. Stace

and patent medicines as well as other employments that are a little murky

to us at present. I'm sure that ERB was seen as socially unacceptable.

Thus Bridge who has lived among the hoboes has never partaken of their

crimes so there is no reason for society to reject him especially as he

is the son of a multi-millionaire.

In any event ERB left Chicago for the Coast

returning in 1917 then leaving for good at the beginning of 1919.

Life ain't easy. Ask me.

As Bridge, the Kid and the putative Abigail

Prim were finishing breakfast the great detective Burton pulls up in front

of the Squibbs place. Burton is obviously a combination of Sherlock

Holmes and Allan Pinkerton. We have been advised of the Holmes connection

in the opening paragraphs of the book. ERB describes Burton thusly:

Burton made

no reply. He was not a man to jump to conclusions. His success

was largely due to the fact that he assumed nothing; but merely ran down

each clew quickly yet painstakingly until he had a foundation of fact upon

which to operate. His theory was that the simplest way is always

the best way. And so he never befogged the main issue with any elaborate

system of deductive reasoning based on guesswork. Burton never guessed.

He assumed that it was his business to know; nor was he on any case long

before he did know. He was employed now to find Abigail Prim.

Each of the several crimes committed the previous night might or might

not prove a clew to her whereabouts; but each must be run down in the process

of elimination before Burton could feel safe in abandoning it.

That's a pretty good understanding of Doyle's

presentation of Holmes. ERB did leave out Holmes' dictum that it

was necessary to read all the literature on the subject to understand the

mentality of one's subjects. Burton did demonstrate some acumen in

his arrest of Dopey Charlie and the General. He deployed an agent

fifty yards below and fifty yards above to converge on the two criminals

while he approached from the front. Either Burroughs had been doing

some reading or he picked up some experience or information from somewhere.

Another keen point was when Burton went back to where the hoboes had

been hiding to dig up the evidence they had concealed that would lead to

their conviction for the Baggs murder.

It's little details like these that always

make me wonder where Burroughs picked up this stuff. He does it all

so naturally but one can't write what one doesn't know. He must have

been a very curious man, good memory.

So Burroughs has a pretty good understanding

of Doyle's presentation of Holmes. It must be remembered

that ERB was reading these stories as they first appeared not as we do

as part of literature. Holmes, O. Henry, Jack London, E.W. Hornung

these were all fresh new and extremely stimulating with a great many references

and inferences which undoubtedly are lost on us. Even in 'Bridge

And The Kid' ERB's reference to the Kid's 'bringing home the bacon'

is a direct reference to a quip the mother of the ex-heavyweight champion

of the world Jack Johnson made just after he won the championship.

I don't doubt if many caught it then but I'm sure the phrase has become

such a commonplace today that only a very few catch the reference.

Stories like A

Study In Scarlet dealing with the Mormons and The

Valley Of Fear dealing with the Molly Maguires would have had much

more thrilling immediacy for ERB than they do for us. Also Burroughs

has caught the essence of Holmes which was not so much the stories as the

method of Holmes.

I have read the canon four times and while

I could not reconstruct any of the stories without difficulty, if at all,

maxims like - When you eliminate the impossible whatever remains no matter

how improbable must be the truth.- have lodged in my mind since I was fourteen

organizing my intellect. So also the dictum to read all the literature.

Not easy or even possible, but the more one has read or read again the

more things just fall in place without any real effort. You have

to be able to remember, of course. Holmes has been like a god to

me.

If you wish to learn a source of Burroughs'

stories then all you have to do is apply the above methods. It will

all become clear.

Burton moves the story forward as his appearance

causes Bridge who isn't sure what the status of the Kid and the putative

Gail Prim is elects to avoid the great detective even though they are friends.

The trio slip out the back into the woods following

a track leading to 'Anywhere.' Burroughs in a masterful telling catches

the feel of a Spring day on a recently wetted trail littered with the leaves

of yesteryear. Ou sont les neiges d'antan?

They come upon a clearing where a gypsy woman

is burying a body. By this time Bridge has solved all the mysteries

of the previous evening.

The girls make noises upon hearing the

clank of a chain in the hovel causing the gypsy woman to look around.

Rather than spotting the trio she spots Willie Case hiding in the bushes

who she drags out.

The gypsy woman, Giova, is as good a character

as Bridge, the Kid, Burton and the hoboes, but my favorite of the story

is little Willie Case, the fourteen year old detective. While to

my mind ERB presents Willie as a thoroughly admirable character he vents

a suppressed mean streak not only on Willie but on the whole Case family.

ERB doesn't let his mean streak show very often,

it lurks in the background, but he lets it loose in this book. He

must have been under personal stress.

He describes Willie as having no forehead and

no chin, the face literally beginning with the eyebrows and ending with

the lips. A freak of nature, a real grotesque. that means that

Willie was a real 'low brow' even a no brow. Is it a coincidence

that Emma called ERB a low brow or that the literati thought ERB wrote

'low brow' literature?

In point of fact Willie strikes me as an intelligent

boy. He analyzes the situation always being in the right place at

the right time. Burton himself pays him a high but sneering compliment

then cheats him out of the promised reward of a hundred dollars, half of

which he personally pledged. So much for the ethics of detectives.

How might that be a 'highly fictionalized'

account of Burroughs life. Everyone calls him a low brow, he manages

to write astonishing and very successful stories but in the manner McClurg's

published his books Burroughs was cheated out of his reward.

I don't say it's so but the facts fit the case.

In any event ERB treats the Case family meanly; they might almost be negative

prototypes of Ma and Pa Kettle of the Egg and I or the meanly portrayed

characters of Erskine Caldwell in Tobacco Road. Jeb Case behaves

very reprehensibly at the lynching although once again he merely reported

the facts that the Kid gave Willie. The Kid did tell Willie that

he had burgled a house and killed a man. So, perhaps ERB created

some characters he could kick around as he felt himself being kicked.

In any event ERB treats the Case family meanly; they might almost be negative

prototypes of Ma and Pa Kettle of the Egg and I or the meanly portrayed

characters of Erskine Caldwell in Tobacco Road. Jeb Case behaves

very reprehensibly at the lynching although once again he merely reported

the facts that the Kid gave Willie. The Kid did tell Willie that

he had burgled a house and killed a man. So, perhaps ERB created

some characters he could kick around as he felt himself being kicked.

And then we have the gypsy woman, Giova,.

She and her father are not only pariahs in general society as gypsies but

because of her father they have even been cast out by the gypsies.

Her father was a thief from both general and gypsy society. The former

may have been laudable in gypsy terms but the latter wasn't. They

make, or made, their living by thieving and cadging coins with Beppo their

dancing bear. Beppo of the evil eye.

Burroughs presents her as being sexually attractive

with lips that were made for kissing in echo of the refrain from 'Out There

Somewhere.' Here we may have a first inference that Emma was in trouble;

the kind of trouble that would have ERB leaving her for another woman a

decade or so hence. There are numerous rumblings indicating the trend

not least of which was ERB's fascination with Samuel Hopkins Adams' novel

Flaming

Youth of a few years hence and the subsequent movie of the same

name starring Colleen Moore.

Bridge is now on the run with three women and

a bear and he hasn't done anything wrong to get into such hot water.

One woman his emergent Anima, one his rejected Anima and the last a longing

for a woman with lips made for kissing. Wow! This is all taking

place in a ravine that opens into a small valley too.

All this has been accomplished in a compact

one hundred pages. One third of the book is left for the denouement

which Burroughs scamps as he commonly does.

Giova decks them all out as gypsies which must

have been an amusing sight to the Paysonites as this troop of madcaps with

dancing bear in tow troop inconspicuously through town. Surprised

they didn't call out the national guard just for that.

As the story draws to a close ERB contributes

a wonderful vignette of low brow Willie dining out at a 'high brow' restaurant

called The Elite in Payson. The idea of Willie being conspicuous

in a burg like Payson which we big city people would refer to as a hick

town good only for laughs is amusing in itself. You know, it all

depends on your perspective.

Willie Case

had been taken to Payson to testify before the coroner's jury investigating

the death of Giova's father, and with the dollar which the Oskaloosa Kid

had given him in the morning burning in his pocket had proceeded to indulge

in an orgy of dissipation the moment that he had been freed from the inquest.

Ice cream, red pop, peanuts, candy, and soda water may have diminished

his appetite but not his pride and self-satisfaction as he sat down and

by night for the first time in a public eatery place Willie was now a man

of the world, a bon vivant, as he ordered ham and eggs from the pretty

waitress of The Elite Restaurant on Broadway; but at heart he was not happy

for never before had he realized what a great proportion of his anatomy

was made up of hands and feet. As he glanced fearfully at the former,

silhouetted against the white of the table cloth, he flushed scarlet, assured

as he was that the waitress who had just turned away toward the kitchen

with his order was convulsed with laughter and that every other eye in

the establishment was glued upon him. To assume an air of nonchalance

and thereby impress and disarm his critics Willie reached for a toothpick

in the little glass holder near the center of the table and upset the sugar

bowl. Immediately Willie snatched back the offending hand and glared

ferociously at the ceiling. He could feel the roots of his hair being

consumed in the heat of his skin. A quick side glance that required

all his will power to consummate showed him that no one appeared to have

noticed his faux pas and Willie was again slowly returning to normal when

the proprietor of the restaurant came up from behind and asked him to remove

his hat.

Never had Willie Case spent

so frightful a half hour as that within the brilliant interior of the Elite

Restaurant. Twenty-three minutes of this eternity was consumed in

waiting for his order to be served and seven minutes in disposing of the

meal and paying his check. Willie's method of eating was in itself

a sermon on efficiency- there was no waste motion- no waste of time.

He placed his mouth within two inches of his plate after cutting his ham

and eggs into pieces of a size that would permit each mouthful to enter

without wedging; then he mixed his mashed potatoes in with the result and

working his knife and fork alternatively with bewildering rapidity shot

a continuous stream of food into his gaping maw.

In addition to the meat

and potatoes there was one vegetable in a side-dish and as dessert four

prunes. The meat course gone Willie placed the vegetable dish on

the empty plate, seized a spoon in lieu of a knife and fork and- presto!

the side dish was empty. Where upon the prune dish was set in the

empty side-dish- four deft motions and there were no prunes in the dish.

The entire feat had been accomplished in 6:34 1/2, setting a new world's

record for red headed farm boys with one splay foot.

In the remaining twenty-five

and one half seconds Willie walked what seemed to him a mile from his seat

to the cashier's desk and at the last instant bumped into a waitress with

a trayful of dishes. Clutched tightly in Willie's hand was thirty-five

cents and his check with a like amount written upon it. Amid the

crash of crockery which followed the collision Willie slammed check

and money upon the cashier's desk and fled. Nor did he pause until

in the reassuring seclusion of a dark side street. There Willie sank

upon the curb alternately cold with fear and hot with shame, weak and panting,

and into his heart entered the iron of class hatred, searing it to the

core.

The above passage has many charms. First

it is an excellent piece of nostalgia now although at the time it represented

the actuality, thus, as a period piece it is an accurate picture of the

times. And then it is excellent comedy as well as a parody or two

as I will attempt to show.

One has to wonder if ERB really thought the

Elite was a pretty fine restaurant. If so, one wonders where he took

Emma and kids for a night out. Not too many gourmet Chicago restaurants

served breakfast for dinner. Ham and eggs with mashed potatoes?

reminds me of the Galt House Hotel in Louisville where a 'starch' is served

as a side-dish. What exactly was this side-dish Willie wolfed- stewed

tomatoes? The dessert prunes- dessert prunes?- was nice touch too.

Dessert for breakfast? Another nice quality touch at the Elite was

the cup of toothpicks. Of course, those were the days cuspidors were

de rigeur so what do I know, maybe the Palmer House had a cup of toothpicks

too, I know they had cuspidors.

It does seem clear that little Willie was far

down the social scale of little rural Payson. They had electric street

lights, though. I'm not even from New York City but I would find

the Elite, how shall I say, quaint and charming? Of course, New York

City is not what it used to be either. Can't fool me in either case;

I've dined out in Hannibal. Good prices. Bountiful.

I'm sure I've been in Willie's shoes, or would

have been if he'd chosen to wear them, too so I have a great deal

of sympathy for the lad. A man with a dollar has the right to spend

it where and as he chooses. Damn social hypocrisy!

In addition to the charm and light comedy ERB

interjects a little parody of Taylorism and mass production into the mix.

For those not familiar with Frederick W. Taylor

and his methods I quote from http://instruct1.cit.cornell.edu/courses/dea453-653/ideabook1/thompson-jones/Taylorism.htm

:

Frederick Taylor

wrote 'The Principles of Scientific Management in 1911, these principles

became known as Taylorism. Some of the principles of Taylorism include

(Management for Productivity, John R. Schermerhorn, Jr. (1993)):

-

Develop a 'science' for every job, including

rules motion, standardized work implements, and proper working conditions.

-

Carefully select workers with the right abilities

for the job.

-

Carefully train these workers to do the job, and

give them proper incentives to cooperate with the job science.

-

Support these workers by planning their work and

by smoothing the way as they go about their jobs.

Taylorism which led to maximum efficiency also

gives the lie to the unconscious of Sigmund Freud, or at least, puts it

into perspective. If the twentieth century has been the history of

the devil of Freud's unconscious it has also the been the century of the

triumph of the god of conscious intelligence. The question only remains

which will triumph.

One of the recurring themes in ERB's writing

of the period is efficiency. Indeed, a couple years hence he would

write a book entitled The

Efficiency Expert.

It was the age of efficient mass production

which required standardized motions and produced terrific results where

applied as at Henry Ford's marvelously efficient factories. Ford brought

the task to the worker in well lighted clean factory spaces at a level

which required no time consuming, fatiguing and unnecessary lifting or

bending. Plus Henry Ford blew the industrial world away by doubling

the going wage for this unskilled labor. He changed the course of

economic history singlehanded. He achieved more than the Communists

or IWW could have accomplished in a million years earning their undying

enmity. He may have in one fell swoop defeated the Reds.

But, go back and review how Willie organizes

his repast for consumption. Taylor like he eliminated all non-essential

motions then with maximum assembly line speed up he gets production into

one continuous stream.

A comic effect to be sure but there is even

more comedy in the parody of the assembly line and Taylorism. I'm

sure ERB intended it just that way.

Willie may be a joke but there is a certain

flavor to be obtained by filling a continuum of food, mouth and time.

Such an opportunity for enjoyment may present itself once in ten years

or so. Willie saw his opportunity and seized it which he does throughout

the story. Willie's OK by me.

I have eaten that way but I now reserve the

method for Ice cream and highly recommend it. My last opportunity,

they present themselves but rarely and can't be forced, was several years

ago when I was insultingly offered a half melted Cherries Jubilee.

The dish was perfect for assembly line consumption. I saw my chance

and like Willie I took it. I kind of distributed cherries and ice

cream chunks in the creamy stew, got my mouth in the right position and

cleaned the bowl in 60 seconds flat, reared back gripping the bridge of

my nose, honked a couple times as the freeze seized my brain then took

a few minutes for consciousness to return. I tell ya, fellas, they

was all lookin' at me but I am much beyond the iron of class hatred.

The Elite may have made a socialist of Willie

but Wilf's made a sneering elitist out of me. Superior, boys, superior,

that's what I became, one of Nietsche's and London's great Blond Beasts.

I had to get a peroxide job to look to the part but wotth'ell no sacrifice

is too great for my art. Besides, consider, I've forgotten Wilf's,

never went back, and the people I was with, but I'll always, always remember

those Cherries Jubilee.

So, I think Willie Case did the right thing.

Clumsy waitress to get in his way anyway.

Fourteen hours on the job was no excuse.

Willie didn't feel guilt for too long though,

for what ERB calls his faux pas, it put him in the right place at the right

time to see Giova and her dancing bear fresh from Beppo's own slops.

How could ERB be so cruel to a dumb animal- the bear, not Willie-, one

that was going to save his heroine's life- both the bear and Willie.

After having had dinner and refreshments Willie

still had 20 cents left from a dollar of which he spent 10 cents for a

detective movie and had ten cents left over for a long distance telephone

call to Burton in Oakdale after he spotted Giova and her dancing bear when

he came out of the movie theatre.

He followed Giova to Bridge and the girls,

fixed their location then called Burton. Not only did Willie spot

the fugitives but so did the dour leftover bums. Dopey Charlie and

the General were impounded for the Baggs murder while we will learn that

the real Oskaloosa Kid and his 'pal' cracked up Paynter's car in Toledo,

whether Ohio or Illinois we aren't told.

All the mysteries are being concluded.

The last two, who is the faux Oskaloosa Kid and the putative Gail Prim

remain as well perhaps as the true identity of L. Bridge.

Burroughs is full of interesting details.

The hoboes are gathered in an abandoned electrical generating plant which

had formerly served Payson but had been discontinued for a larger plant

servicing Payson from a hundred miles away. We don't know when that

might have happened but electrical generation and distribution was relatively

new. The consolidation into larger generating units was even newer.

Samuel Insull, whose electrical empire crashed about 1938 had begun organizing

distribution in 1912 when he formed Mid-West Utilities from Chicago absorbing

all the smaller companies such as this one in Payson, obviously.

I find details like this the exiting part of

reading Burroughs.

The murderous hoboes set out to rob and kill

Bridge and the Kid while Sky Pilot and Dirty Eddie elect themselves to

return the putative Gail Prim who we will learn is actually Hettie Penning,

a wayward, but not a bad girl.

One is put in mind of the Hettie of H.G. Wells'

novel In

The Days Of The Comet. Both Hetties exhibit the same traits.

While it may seem a slender connection, still ERB has so many references

to other authors and their works the connection is not improbable.

For obvious reasons ERB always insisted he had never read H.G. Wells, Wells

who?, but how could he not have?

Bridge and the girls would have met their end

except that Willie Case's call brought Burton on the run who arrives in

time to save their lives. Unfortunately Beppo of the evil eye meets his

end after having done Burton's job for him much as Willie always did.

In between the girls, the 'boes, Bridge and

the coppers Burton has a full load so he drops Bridge and the Kid at the

Payson jail. Willie Case had not only solved the case for the ingrate

Burton but saved the life of Gail Prim as the Oskaloosa Kid. In a

heart wrenching scene little Willie seeking his just reward is cruelly

rejected by the Great Detective. I don't know, maybe I read too closely

and get too involved. Or, just maybe, ERB is a great writer.