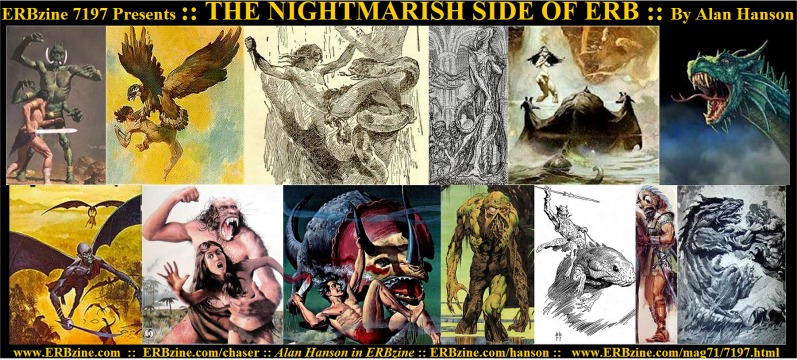

The Nightmarish Side of

Edgar Rice Burroughs

by Alan Hanson

In 1889, while working with his brothers dredging for

gold on the Snake River, a 24-year-old Edgar Rice Burroughs got in the

way of a constable’s billy club during a brawl in an Idaho saloon. Thirty

years later, in a letter to the Boston Society of Psychic Research, he

described the resulting injury. “I received a heavy blow on the head

which, while it opened up the scalp, did not fracture the skull, nor did

it render me unconscious.” While this injury caused no physical disability,

it may have triggered a psychological affliction from which ERB suffered

for the rest of his life. In the aforementioned letter, Burroughs went

on to explain, “For six weeks or two months thereafter I was the victim

of hallucinations, always after I had retired at night when I would see

figures standing beside my bed, usually shrouded. I invariably sat up and

reached for them, but my hands went through them. I knew they were hallucinations

caused by my injury.”

While Burroughs experienced the “shrouded” figures

dream for no more than two months after the Idaho saloon incident, he was

to suffer from intense and terrifying nightmares periodically for the next

50 years. His later phenomenal success indicates that ERB learned to live

with his nocturnal tortures. Ironically, his nightmares may have had a

positive influence in his life. It has been suggested by some, even Burroughs

himself, that his persistent nightmares provided a dark reservoir from

which he conjured up some of his frightful characters and fantastic storylines.

Did Edgar Rice Burroughs use his nightmares as a source for his fiction?

And, if so, to what extent? Those are the questions to be considered here.

The first step to answering them is to understand as clearly as possible

the nature of ERB’s nightmares.

Fearful Creatures Menaced

ERB in His Sleep

To begin with, even on the calmest of his nights, Burroughs

was a fitful sleeper, as he explained in an interview for old friend Bob

Davis’ column in “The New York Sun” of July 20, 1940. “Am I a good sleeper?

One of the best. I start on the right side, turn over on the left side,

back again to the right side, every fifteen minutes, until I have had enough

of both. I then rise refreshed. Sleeping on my back gives me a nightmare.”

With what regularity nightmares came to him is not known,

but biographer John Taliaferro claims they were so frequent over the years

that ERB’s children and both wives gave up counting them. Even while living

in Hawaii after his second divorce, the nightmares continued. Biographer

Irwin Porges reported that Brigadier General Thomas Green and two of ERB’s

civilian friends, Sterling and Floye Adams, all residents of the Niumalu

Hotel in Honolulu where Burroughs lived, recalled ERB’s frequent nightmares

and how they disturbed other hotel guests staying in nearby rooms.

Common to the content of Burroughs’ countless nightmares

was a recurring framework. Porges described the pattern as follows. “They

occurred regularly and involved the kind of situation, familiar to many

dreamers, where some fearful creature or undefined peril was approaching

the room, and the individual, aware of his danger, tried desperately to

move but found himself paralyzed.”

Notice that this pattern fundamentally differs from the

“shrouded figures” dream that Burroughs experienced for a couple

months after the blow to his head in 1899. In those dreams, which ERB referred

to as “hallucinations,” rather than nightmares, Burroughs was able

to move in his dreams, reaching out for the shrouded figures but unable

to grab them. The paralysis in the face of impending danger, which characterized

his later dreams, was much more intense and resulted in Burroughs reacting

physically to the obvious terror he experienced in his sleep.

As testimony to the realism of his nightmares, ERB twisted

and turned and cried out in his sleep, waking his family and anyone else

within hearing distance of his outbursts. Porges explained that at times

ERB’s wife Emma would have to soothe her agitated husband until he became

calm. His second wife Florence found it hard to sleep in the same room

with ERB, so startling and frightening were his cries in the throes of

a nightmare. Of the Hawaii years, General Green reported, “Those who

resided close to Ed’s shack recall numerous occasions when Ed would have

wild nightmares and emit sounds not unlike his ‘Tarzan of the Apes.’”

Nightmares or Daydreams?

It is unclear if Burroughs could actually see the creatures

that menaced him during those nightmares or whether he was terrified by

the approach of some unseen danger. It was inevitable, however, considering

the nature of frightful creatures that turned up in his fiction, that someone

would bring up a possible connection between Burroughs’ nightmares and

his fiction. That connection was first suggested by Alva Johnston in his

1939 article, “How to Become a Great Writer,” which appeared in

“The Saturday Evening Post.” That article includes the following

passage, which Johnston obviously culled from an interview with ERB.

“He was too poverty-stricken to pay for any of the

tired businessman’s relaxations, but he hit upon a free method of making

himself feel better. When he went to bed, he would lie awake, telling himself

stories. His dislike of civilization caused him frequently to pick localities

in distant parts of the solar system. Every night he had his one crowded

hour of glorious life. Creating noble characters and diabolical monsters,

he made them fight in cockpits in the center of the earth or in distant

astronomical regions. The duller the day at the office the weirder his

nightly adventures. His waking nightmares became long-drawn-out action

serials.”

Notice that Johnson did not suggest that Burroughs’ story

ideas and characters were born in actual nightmares, but rather in “waking

nightmares,” essentially ERB’s evening daydreams. Still, Johnson’s

use of the term “nightmare” may have been enough to set the idea

in many a reader’s mind that Burroughs conjured up his stories and characters

from his real nightmares.

In his Burroughs biography, Porges went out of his way

to debunk this notion.

“Statements or suppositions that these nightmares contained

fantasy scenes of other worlds or dangerous encounters with creatures of

the type created by Ed in his stories, and that he would draw upon these

nocturnal adventures for his plots are unfounded. His nightmares should

not be confused with his daydreams during which he might devise characters

and situations in his stories.”

Apparently, however, on at least one occasion, Burroughs’

himself encouraged the notion that he drew story material from his nightmares,

although one person who heard ERB say as much obviously questioned the

author’s sincerity. In the Porges biography, General Green recalled conversations

with Burroughs in Hawaii.

“Ed would tell us that he actually dreamed up some

of the characters and plots for his stories and would arise in then night

and jot down notes while the thoughts were fresh in his mind. We always

wondered if he was being factual. However, he was writing about one novel

a year at the time, and having read one of his works of that period which

he autographed, I can believe that the characters were born out of one

of his nightmares.”

Tarzan’s Nightmare

Knowing what there is to know about the nightmares of

Edgar Rice Burroughs, then, it is time to turn to his fiction to see if

there is evidence that his nightmares were source material for his stories.

ERB wrote only one story that had a plot based on a nightmare. In 1917

Burroughs was 41 years old and temporarily living in Los Angeles when he

wrote a short story entitled, “The Nightmare,” which was destined

to be the ninth of twelve chapters in Jungle Tales of Tarzan.

By 1917 Burroughs had experienced periodic nightmares for nearly two decades,

and so it is possible he used elements of his own bad dreams to construct

Tarzan’s first nightmare.

In the story Tarzan’s nightmare resulted from eating spoiled

elephant meat that the ape-man stole from a cooking pot in Mbonga’s native

village. After falling asleep in the bole of a tree, Tarzan experienced

a series of hallucinations, which, taken together, made up not only his

first nightmare, but also his first dream, according to Burroughs. The

first hallucination involved a lion climbing the tree to attack Tarzan.

The paralysis in the face of danger that Burroughs experienced in his nightmares

was mirrored in Tarzan’s sluggish movement.

“As the lion climbed slowly toward him, Tarzan sought

higher branches; but to his chagrin, he discovered that it was with the

most utmost difficulty that he could climb at all.”

“Clawing desperately” to escape, Tarzan finally

reached the tallest branch, some 200 feet above the jungle floor. When

“devil-faced Numa” kept coming, however, the ape-man realized that

death was near. He was saved from the tree-climbing lion, when a huge bird

buried its talons in the dreamer’s back and carried him aloft. After stabbing

the bird three times with his knife, Tarzan was dropped and fell perhaps

a thousand feet to land in the same tree where he had fallen asleep. Tarzan

awoke briefly, but when he fell asleep again, the hallucinations continued.

First, a snake with the head and stomach of a native he had killed in Mbonga’s

village came at Tarzan, but disappeared when the ape-man “struck furiously

at the hideous face.” This was followed the rest of the night by other

hallucinations that Burroughs did not detail.

On the surface, Tarzan’s dream does not seem to fit the

pattern of ERB’s own nightmares. Tarzan did face a menacing danger, as

ERB did in his dreams, but while the ape-man moved sluggishly in his first

hallucination with the lion, he later was able to vigorously defend himself

in the encounters with the giant bird and the snake. Burroughs, as noted

earlier, was unable to move at all when menaced in his own nightmares.

Also, ERB gave Tarzan a series of hallucinations, while the author seemingly

suffered but one terrifying encounter in his tortured sleep. Additionally,

Tarzan’s nightmare was caused by something he ate, while Burroughs’ nightmares

were chronic and the result of unknown causes.

There are a couple of elements, though, that Burroughs

might have borrowed from his dreams and inserted in Tarzan’s. First, the

ape-man’s dream seemed so real to him that he had trouble differentiating

his sleep adventures from reality, this despite the fact that he realized

while dreaming that lions could not climb trees and that no giant birds

existed in his jungle. Perhaps ERB was recalling the terrifying reality

of his own dreams and gave the same feeling to Tarzan. Second, Tarzan realized

that he was not the same person in his dreams as he was during his waking

hours. In thinking back to his nightmare, Tarzan saw his dream counterpart

was a lesser man, “sluggish, helpless and timid — wishing to flee his

enemies.” The pattern of ERB’s nightmares makes it clear that he felt

similar inadequacies in his dreams.

Barsoomian, Amtorian,

and Pellucidarian Nightmares

While Burroughs may have included a few aspects of his

own nightmares in “The Nightmare,” it appears quite unlikely that

he based the story and its menacing creatures on anything specific he saw

in his own dreams. Before moving on to look at other Burroughs fictional

nightmares, it is worth noting at this point that ERB obviously did not

think it was a sign of weakness for a man to have nightmares. In addition

to Tarzan, other Burroughs heroes, including David Innes, Carson Napier,

and Jason Gridley, experienced nightmares. The dreams of David Innes, for

instance, never let him forget being carried through the treetops by ape-things

soon after arriving in Pellucidar. “Never have I experienced such a

journey before or since,” David recalled in At the Earth’s Core.

"Even now I oftentimes awake from a deep sleep haunted by the horrid

remembrance of that awful experience."

Porges characterized the danger that menaced Burroughs

in his nightmares as “some fearful creature or unidentified peril.”

When ERB’s fictional characters experienced nightmares, however, they often

could identify who or what was threatening them. For example, in The

Mucker, Barbara Hardings’ fear of Billy Byrne extended into her

dreams. Burroughs wrote, “So vivid an impression had his brutality made

on her that she would start from deep slumber, dreaming that she was menaced

by him.” Again, early on in The Cave Girl, Waldo Emerson

Smith-Jones had never seen the cavemen Flatfoot and Korth, but Nadara’s

description of them was enough to give him nightmares about them. “Horrible

visions of Flatfoot and Korth haunted his dreams,” ERB explained. “He

saw the great, hairy beasts rushing upon him in all the ferocity of their

primeval savagery — tearing him limb from limb in their bestial rage. With

a shriek he awoke.”

The Burroughs character who experienced a nightmare closest

to the type ERB experienced, was Pan-at-lee, a Waz-don maiden of Pal-ul-don

in Tarzan the Terrible. Her nightmare contained a menacing

“fearful creature” and paralysis in the face of danger, both of

which Burroughs experienced.

“Pan-at-lee slept — the troubled sleep, of physical

and nervous exhaustion, filled with weird dreamings. She dreamed she had

slept beneath a great tree in the bottom of the Kor-ul-gryf and that one

of the fearsome beasts was creeping upon her but she could not open her

eyes nor move. She tried to scream but no sound issued from her lips. She

felt the thing touch her throat, her breast, her arm, and then it closed

and seemed to be dragging her toward it. With a super-human effort of will

she opened her eyes. In the instant she knew that she was dreaming and

that quickly the hallucination of the dream would fade — it had happened

to her many times before. But it persisted. In the dim light that filtered

into the dark chamber she saw a form beside her, she felt hairy fingers

upon her and a hairy breast against which she was being drawn. Jad-ben-Oth!

this was no dream.”

Burroughs used this particular kind of nightmare, in which

dream merges with reality as the dreamer awakes, a number of times in his

fiction. In Pan-at-lee’s case, the horror of the nightmare was extended

into reality, the fearsome creature of her dream continuing to menace her

after she awoke. A variation of this dread-reality merger that ERB sometimes

used could be called a “reverse nightmare.” In such cases, the victim

has a pleasant dream, only to awaken into a nightmarish reality. Take,

for example, Virginia Maxon’s experience in The Monster Men.

“It was daylight when she awoke, dreaming that the

tall young giant had rescued her from a band of demons and was lifting

in her arms to carry her back to her father. Through half open lids she

saw the sunlight filtering through the leafy canopy above her — she wondered

at the realism of her dream; full consciousness returned and with it the

conviction that she was in truth being held close by strong arms against

a bosom that throbbed to the beating of a real heart. With a sudden start

she opened her eyes wide to look up into the hideous face of a giant ourang-outang.”

It is doubtful that when ERB wrote one of these dream-reality

merger scenes he was recreating his own experience. Certainly none of the

fearsome creatures that menaced him in his nightmares were there to greet

him when he awoke, and ERB several times wrote of the great relief he felt

when awakening to realize his nightmare had no connection with reality.

When ERB was having a nightmare, what troubled those around

him, of course, was his thrashing about and crying out in his sleep. Few

of ERB’s fictional characters who had nightmares were thus animated during

the experience, but one who mimicked Burroughs’ behavior was Jason Gridley

in Tarzan at the Earth’s Core.

“Jason gradually drifted off into deep slumber, which

was troubled by hideous dreams in which he saw Jana in the clutches of

a Horib. The creature was attempting to devour the Red Flower of Zoram,

while Jason struggled with the bonds that secured him. He was awakened

by a sharp pain in his shoulder and in opening his eyes he saw one of the

monosaurians, as he had mentally dubbed them, standing over him, prodding

him with the point of his sharp lance. ‘Make less noise,’ said the creature,

and Jason realized he must have been raving in his sleep.”

Burroughs’ tossing and turning and ranting and raving

during his nightmares attests to the genuine horror he felt during those

nocturnal episodes. It could be that when he wrote the following passage

in I Am a Barbarian, he was remembering the real suffering

he was experienced in his own bad dreams. In the story, the slave hero

Britannicus feared Roman justice for having killed a Roman citizen. “I

spent sleepless nights,” explained Britannicus, “and when I did

sleep my dreams were horrid dreams. From thinking of the tortured creatures

along the Via Flaminia, I dreamed of them. Only it was I upon a cross in

my dreams. Had it been the reality, I could not have suffered more. I awoke

bathed in cold sweat.” If ERB ever awoke in a “cold sweat,”

it’s possible that the relief he felt at realizing the nightmare was over

could not completely assuage the suffering he had endured during the dream.

In Escape on Venus, written in 1940 in Hawaii

during a period when ERB was particularly savaged by nightmares, Burroughs

had his hero Carson Napier experience a nightmare. “I saw the anotar

crash,” Napier recalled, “and I saw Duare’s broken body lying dead

beside it. I don’t believe in dreams, but why did I have to dream such

a thing as that?” It would be interesting to know if ERB wondered,

as did Carson, about the psychological significance of nightmares. Porges

did not touch upon the issue, but Taliaferro did. In his Burroughs biography

he mentions a letter which ERB wrote to his son Jack in late 1931. In the

letter, ERB described a recent dream. “Last night I dreamed that Mama

and I were in a bedroom that was unfamiliar to me.” Taliaferro then

paraphrased, “The rest of the reverie concerned an intruder, Burroughs’s

paralysis in the presence of danger, a mysterious key, and a vague but

pressing sense of entanglement.” Taliaferro speculated that ERB saw

some connection between this dream and the marital problems he and Emma

were having at the time. They separated two years later.

“Nighmarish Creatures”

— Tharks, Number One, Coripies, Wieroos

Porges mentioned that “fearful creatures” menaced

Burroughs in some of his nightmares, and we have General Thomas Green’s

testimony that ERB claimed some of his fictional monsters were based on

what he had seen in his dreams. If true, (and Burroughs may have been pulling

General Green’s leg about it), it would be interesting to know just which

of his fictional creatures were born in his nightmares. Burroughs did not

directly associate the Green Martians, the very first non-human race he

created in his fiction, with a nightmare. When John Carter first saw the

approaching Tharks in A Princess of Mars, he referred to

them as a “materialized nightmare.” One can understand Carter’s

initial judgment, considering charging down upon him was a fifteen-foot

high, four hundred pound, six-limbed, sword wielding creature, a “huge

and terrific incarnation of hate, of vengeance and of death.”

However, by the end of A Princess of Mars,

Burroughs had transformed this band of Tharks into John Carter’s trusted

allies. The capacity for loyalty, courage, and friendship that ERB embodied

in the Tharks took away their initial frightful and caused the reader to

like, and perhaps even feel affection, for them. If something that looked

like a Thark was one of the “fearful creatures” ERB saw in his nightmares,

he was certainly forgiving when he made them such admirable creatures in

his fiction.

There are a number of other creatures in ERB’s stories,

however, that could have been born, if not directly in his nightmares,

than certainly in the nightmarish side of ERB’s imagination. As examples,

consider the three following ghoulish creatures conceived by Edgar Rice

Burroughs.

The first is Number One, one of Professor Maxon’s soulless

creatures in The Monster Men. Virginia Maxon might very well

have thought she was having a nightmare when she saw Number One approaching

her.

“The thing thrust so unexpectedly before her eyes was

hideous in the extreme. A great mountain of deformed flesh clothed in dirty,

white cotton pajamas! Its face was of the ashen hue of a fresh corpse,

while the white hair and pink eyes donated the absence of pigment; a characteristic

of Albinos. One eye was fully twice the diameter of the other, and an inch

above the horizon plane of its tiny mate. The nose was but a gaping orifice

above a deformed and twisted mouth. The thing was chinless, and its small,

foreheadless head surrounded its colossal body like a cannon ball on a

hill top. One arm was at least 12 inches longer than its mate, which was

itself long in proportion to the torso, while the legs, similarly mismatched

and terminating in huge, flat feet that protruded laterally, caused the

thing to lurch fearfully from side to side as it lumbered toward the girl.”

If Number One doesn’t seem menacing enough to you, how

would you like to see a Coripi enter your bedroom at night? When one threatened

Tanar and Stellara in Pellucidar, the sight made the hair rise on the scalp

of the caveman. Tanar was incapable of imagining “a more fearsome or

repulsive thing than that which advancing upon them.” ERB described

the Coripi in great detail, as if he had actually seen one.

“In conformation it was primarily human, but there

the similarity ended … Its arms were short and in lieu of fingers is hands

were armed with three heavy claws. It stood somewhere in the neighborhood

of five feet in height and there was not a vestige of hair upon its entire

naked body, the skin of which was a sickly pallor of a corpse. But these

attributes lent to it but a fraction of its repulsiveness — it was its

head and face that were appalling. It had no external ears, there being

only two small orifices on either side of its head where these organs are

ordinarily located. Its mouth was large with loose, flabby lips that were

drawn back now into a snarl that exposed two rows of heavy fangs. Two small

openings above the center of the mouth marked the spot where a nose should

have been and, to add further to the hideousness of its appearance, it

was eyeless, unless bulging protuberances forcing out the skin where the

eyes should have been might be called eyes. Here the skin upon the face

moved as though great, round eyes were rolling beneath. The hideousness

of that blank face without eyelids, lashes or eyebrows shocked even the

calm and steady nerves of Tanar … Beneath its pallid skin surged great

muscles that attested its great strength and upon its otherwise blank face

the mouth alone was sufficient to suggest its diabolical ferocity.”

By the way, the Coripies

(aka The Buried People) ate human flesh.

As fright-inducing as Number One and Coripies were, however,

the most nightmarish all creatures ERB created would have to be the Wieroos

in The Land That Time Forgot. Bradley and his companions

were searching for a place to scale Caspak’s barrier cliffs, when a Weiroo

first appeared hovering in the air above them. It was not particularly

monstrous looking thing. Bradley described it as a “winged human being

clothed in a flowing white robe.” Another one of the men, Sinclair,

added, “It had big round eyes that looked all cold and dead, and its

cheeks were sunken it deep, and I could see its yellow teeth and thin,

tight-drawn lips — like a man who had been dead a long time.”

Although its appearance was shocking, it was the Weiroo’s

gloomy and foreboding psychological effect on the men that produced its

nightmarish quality. Brady, the first man to see it, wailed, “Holy mother

protect us — it’s a banshee!” The reference was to the spirit in Gaelic

folklore whose wailing foretold the death of a family member. And indeed

the Weiroo did emit a piercing wail that, along with the dismal flapping

of its wings, was said to have “frozen the marrow” of these otherwise

brave men. It was even more frightful when it came after dark, like an

apparition in a nightmare. As its “shadowy form passed across the diffused

light of the flaring camp-fire … an eerie wail floated down from above.”

Psychological Aspects

of ERB’s Nightmares

Was the Weiroo patterned after the “shrouded”

figure ERB saw in his dreams after the blow to the head in 1899? There

is no way of knowing for sure, nor whether or not Burroughs fashioned any

other of his ghastly fictional creatures after what terrorized him in his

sleep. It does appear, however, that Burroughs did use in his fiction some

of the psychological aspects of his own nightmares — the menacing danger,

the heightened fear, the inability to move, the sense of inadequacy felt,

and the dreamer’s illogical sense of reality. The use of some aspects of

his nightmares is just one of many examples of how Edgar Rice Burroughs

merged his own life experiences with his fiction. Clearly, if ERB had not

lived such an interesting life, with all its ups and downs, his fiction

would not have been as interesting either.

In closing this investigation, which admittedly has contained

much speculation about ERB’s nightmares, it is only fair to give him the

last word. Certainly, his nightmares must have been irksome to him, to

say the least, but as the following passage shows, Edgar Rice Burroughs

had the ability to see humor in even this frightening aspect of his life.

This nightmare, related by ERB in a 1943 letter to his daughter Joan, was

an atypical one, quite unlike his standard nightmare, but it apparently

still frightened him, just in a different way.

“Last night I dreamed that I was married again. To

whom, I didn’t find out, but I knew I was married because I was sitting

at a desk with a pile of bills, making out checks. I woke up with a headache.

But what a relief when I realized that it had been only a dream.”

~ THE END ~

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()