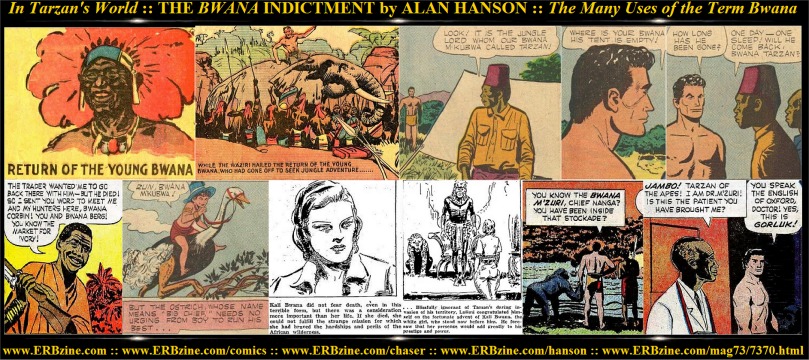

Tarzan and the "Bwana" Indictment

by Alan Hanson

bwana / noun / used as a respectful term of address

for a man in East Africa

As the inclusion of the above definition in the Microsoft

Encarta Dictionary indicates, the term bwana is still in use today

in East Africa. It is a Swahili word, derived from an Arabic term meaning

“our father.” Today bwana could be translated into English

as a commonly used polite title, such as “Sir” or “Mister.”

The term was first used in Africa around the year 1875, which happens to

be the year Edgar Rice Burroughs was born. That timing becomes coincidental

in light of Wikipedia’s assertion that Burroughs’ Tarzan stories

were primarily to blame for a common twentieth century misconception concerning

the meaning of bwana.

According to the popular on-line encyclopedia, “The

word Bwana was often used in Western cinema and books, notably the Tarzan

stories, almost exclusively by subordinate Africans when addressing Caucasian

men.” The Wikipedia entry then offers a passage from Burroughs’

1915 novel, The Son of Tarzan, to illustrate the subservient

context of the term in the Tarzan stories, which were widely read in the

first half of the 1900s.

Some progressive critics have pointed to ethnic

elements in Burroughs’ fiction as evidence that the author painted a racially

inferior view of native Africans. The Wikipedia entry, inferring

that Burroughs purposely used the term bwana to “subordinate Africans”

when addressing whites, is another generalization which, maliciously or

not in intent, serves to discredit the author and discourage the reading

of his fiction in the modern age.

There is no disputing that Burroughs liberally used the

word bwana in his stories set in Africa. The term appears hundreds

of times in nearly two dozen of the author’s Tarzan tales published over

three decades, starting in 1914. The expression even appears multiple times

in Burroughs’ final Tarzan story, which was left unfinished and unpublished

when the author died in 1950.

What warrants close examination, however, is how Burroughs

actually used bwana in his Tarzan stories, and whether or not those

uses indicate the author’s personal belief that blacks were “subordinate”

to whites in Africa during the colonial period. Answering those questions

requires a close look at the term’s many uses in the Tarzan tales. Can

the generalization offered by Wikipedia stand up under close inspection?

Burroughs first used the term in his 1914 novel, The

Beasts of Tarzan. In that story, Tarzan pursues the dastardly villain

Nicholas Rokoff from village to village inland from the East African coast.

The word bwana appears seven times in the text as a term of direct

address used by natives when speaking to Tarzan and the villainous Rokoff.

“No, bwana,” one chief replied when Tarzan questioned him about

Rokoff. “The white child was not with this man’s party.” The same

chief addressed the Russian with the same term. “I will stand with you,

bwana,” he assured Rokoff.

The pattern of black natives addressing white men, both

good and evil, as bwana is repeated throughout the Tarzan stories.

Among the kindly American and English white men who are addressed as bwana

by natives are James Blake in Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle;

Erich von Harben in Tarzan and the Lost Empire; and Jason

Gridley in Tarzan at the Earth’s Core. On the other hand,

Burroughs had natives use the same respectful term to address wicked white

men, including the Swede Malbihn in The Son of Tarzan, the

conspirator Peter Zveri in Tarzan the Invincible, and the

Stalinist spy Leon Stabutch in Tarzan Triumphant.

This pattern in Burroughs’ fiction would seem to support

Wikipedia’s inference that the author portrayed bwana as a term of black

subservience rather than one of respect of one man for another. And, in

fact, several statements by Tarzan seem to indicate he believed that to

be the case. In Tarzan Triumphant, the ape-man confronted

a native who had deserted the white leader of his safari. “Who are you,

to question Goloba, the headman? Get out of my way,” demanded the native,

unaware of his questioner’s identity. Tarzan stood his ground and responded,

“Goloba should know better than to speak thus to any white man.”

The “Law of the Safari”

Seemingly counter to Tarzan’s presumption here that no

native should speak insultingly to any white man are numerous other statements

in which the ape-man indicated that the life of a white man in the jungle

was no more important to him than that of a black man, or even of an animal.

In Goloba’s case, Tarzan confronted the headman because he had violated

what Tarzan called “the law of the safari,” which dictated that,

“those who desert their white masters are punished.” (Tarzan

and the Forbidden City)

Elsewhere in the Tarzan series, Burroughs clarified the

relationship between “the law of the safari” and the deferential

use of the term bwana. In Tarzan and the Lost Empire,

the ape-man confronted the natives who deserted Erich von Harben in the

Wiramwazi Mountains. “Go your way back to your own villages in the Urambi

country,” Tarzan told them. “If your Bwana is dead, you shall be

punished.” Then in Tarzan and the Leopard Men, the safari

natives who abandoned Kali Bwana were later hunted down. “We heard rumors

of the desertion of your men,” a white military officer later told

her. “We arrested some of them in their villages and got the whole story.”

In Tarzan’s Africa, natives who agreed to serve as porters

and askaris in a white man’s, or woman’s, safari were charged with the

protection of their employer until he had discharged them. Contained in

that obligation was the commitment, as Burroughs saw it, to address the

safari’s white leader by the respectful title of “bwana.”

When American Stanley Wood approached the city of Athne in Tarzan

the Magnificent, he told the natives who accompanied him to return

to their homes. The headman shook his head. “We cannot leave the bwana

alone,” he declared.

To Tarzan this unquestioned obedience of safari natives

to their white master was necessary for the safety of all concerned. The

native porters, whose service often took them far from their own country,

relied on their white master’s leadership. When the villainous Michael

Dorsky was killed in Tarzan the Invincible, his safari blacks

“felt very much alone and helpless without the guidance and protection

of a white master.”

Burroughs portrayed the discipline of an African safari

as being much like that on a ship at sea. Like a ship’s captain, it was

essential that a safari’s white leader display firm leadership and command

respect. While many of Burroughs’ white hunters were kindly bwanas, Tarzan’s

Africa had its Captain Blys, as well. The Spaniard Esteban Miranda whipped

his porters in Tarzan and the Golden Lion, and Old Timer

abused his native followers in Tarzan and the Leopard Men.

To their men they were “bad bwanas,” but bwanas nevertheless.

Wilbur Stimbol proved to be another “bad bwana”

in Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle. The American banker, along

with fellow American James Blake, formed a safari and traveled inland to

hunt big game. When Stimbol’s abuse of the native carriers angered Blake,

the two decided to split the safari and go their separate ways. The problems

that arose over the division of the safari reveal how Burroughs viewed

the reciprocal obligations of bwanas and natives in these white-led African

expeditions.

“It will be necessary for half of you to accompany

Mr. Stimbol back to the coast,” Blake told the assembled blacks. “He

will pay double wages to all those who go with him, provided you serve

him loyally.” A native spokesman responded, “No one will accompany

the old bwana. All will go with the young bwana.” Blake reminded the

porters that they had agreed to serve until the safari returned to the

coast. “We agreed to come out with both of you and return with both

of you,” the headman explained. “There was nothing said about returning

separately. We will live up to our agreement and the old bwana may return

in safety with the young bwana.”

Tarzan soon arrived on the scene to deal with the matter.

He divided the blacks into two groups. Blake, with his half, was allowed

to continue hunting in Tarzan’s country. Turning to the headman of the

second group, the ape-man directed, “Escort the older bwana to the railhead

in the most direct route and without delay. He is not permitted to hunt

and there will be no killing except for food or self-defense. Do not fail

me.”

“The law of the safari,” as Burroughs labeled it,

then, dictated that natives loyally serve their employers, usually white

hunters, and fulfill their obligation to safely return their white leaders

to civilized outposts. In the context of safaris in Burroughs’ fiction,

then, the use of the term bwana demonstrated respect, or deference,

of employee to employer, and did not signify subordination of blacks to

whites, as the Wikipedia entry contends.

The “Big Bwana” Tarzan

A separate and totally different use

of the term bwana by Burroughs in his Tarzan stories involves the relationship

between the ape-man and members of the native Waziri tribe. In the 1913

novel, The Return of Tarzan, the Waziri chose the ape-man

as their new king after Tarzan had led the tribe to a victory over the

Arab raiders who had killed their hereditary king. In the remainder of

that story, members of the tribe addressed Tarzan as “king” or “Waziri.”

(By tradition, tribal kings took the tribe’s name as their own.)

However, when Burroughs wrote The Son of Tarzan

two

years later, he had the Waziri begin addressing Tarzan as “Bwana.”

Several times Burroughs reaffirmed that Tarzan was the tribe’s king, but

henceforth he would be “Bwana” to his native subjects.

The change of designation was dictated by a change in

Tarzan’s status. After Tarzan assumed the hereditary title of Lord Greystoke

following the events of The Return of Tarzan, Burroughs decided

to remove his ape-man from the West African jungle and install him as a

wealthy landowner in British East Africa. The author also chose to move

Tarzan’s Waziri tribe eastward across the continent to live near Lord Greystoke’s

estate. (The Waziri first appeared there in Burroughs’ 1914 novel, The

Eternal Lover.)

In this and multiple future Tarzan stories, the Waziri

always addressed their king as “Bwana,” or occasionally as “master.”

In conversation, the Waziri often referred to Tarzan as the “Big Bwana,”

and other natives and Arab interlopers living on or near Lord Greystoke’s

vast estates knew him by that exalted title, as well.

(As an interlude, it should be noted here that in The

Son of Tarzan, the term “Bwana” appears nearly 100 times,

which constitutes about 25 per cent of the term’s total usage in all of

Burroughs’ Tarzan stories. The vast majority of the term’s use in that

novel, however, stems from the author’s efforts to conceal Tarzan’s identity

throughout the second part of the story. When Meriem comes out of the jungle

to live with Tarzan and Jane, she calls him “Bwana,” that being

how she first had heard him addressed. Only the most gullible of readers

would fail to recognize Tarzan as Burroughs continually referred to him

only as “Bwana.” These hundred uses of the term certainly indicate

no subservience on the part of blacks to Tarzan.)

Apparently, Burroughs felt that, in the new East Africa

setting, it would be inappropriate for the tribe to address Tarzan as “king”

and confusing to address him as “Waziri.” Therefore, he changed

the title by which the Waziri people addressed their king to “Bwana,”

a term that was commonly being used by 1915 by native blacks to address

the white British landowners on whose estates they lived in British East

Africa.

For the Waziri, though, addressing Tarzan as “Bwana”

did not indicate subordinate status to the white landowner, Lord Greystoke,

but rather indicated respect for their sovereign leader. Now, whether or

not it was appropriate for Burroughs to portray a white, European aristocrat

as the king of a black African tribe is a related and debatable issue,

but the context in which the Waziri referred to Tarzan as “Bwana”

was essentially the same as British citizens addressing their political

leader as “King.”

Burroughs best expressed the relationship between Tarzan

and the Waziri in the following passage from The Eternal Lover:

“Instantly a hundred warriors sprang to arms, and then,

as quickly, they relaxed, as with shouts of “Bwana! Bwana!” they ran toward

the bronzed giant standing silently in their midst. As to an emperor or

a god they went upon their knees before him, and those that were nearest

him touched his hands and his feet in reverence; for to the Waziri Tarzan

of the Apes, who was their king, was yet something more and of their own

volition they worshipped him as their living god.”

Therefore, the dozens of times the Waziri people refer

to their king, Tarzan, by the term “Bwana” can also be disqualified from

Wikipedia’s charge that Burroughs used the term to “subordinate Africans

when addressing Caucasian men.”

Jane and Gonfala—Female

“Bwanas”

Also not within the framework of the

Wikipedia

indictment of Burroughs are the 36 times the author used the term “Kali

Bwana” in his 1931 novel, Tarzan and the Leopard Men.

(Kali means “woman” in Swahili.) Like he had used “Bwana”

to hide Tarzan’s identity in The Son of Tarzan, the author

used “Kali Bwana” in Leopard Men to conceal the identity

of the character Jessie Jerome until the story’s final pages. In addition,

considering that her headman tried to rape her and that her entire safari

deserted her in the jungle, having the natives call her “Kali Bwana”

obviously indicated no sense of black subordination toward the American

white woman.

(Incidentally, Jessie Jerome was the only Burroughs female

character that African natives addressed using the bwana term. In

two of his later Tarzan stories, however, Burroughs inserted an alternate

Swahili term intended to show respect for white women. In Tarzan’s

Quest, the ape-man and a handful of his Waziri gazed upon the stronghold

of the savage Kavuru warriors who had kidnapped Jane. When the Waziri leader,

Muviro, said, “We are too few, Bwana,” Tarzan replied, “She is

there … your Memsahib … Would you turn back now, Muviro?” According

to George McWhorter’s Burroughs Dictionary, “Memsahib” is

“native African lingo for a white foreign woman. It derives from a Hindustani

word meaning ‘lady’ or ‘mistress.’” In addition to its use in reference

to Jane in Tarzan’s Quest, the term was used in reference

to Gonfala, Lord Montford’s daughter, in Tarzan the Magnificent.)

The time has come to pass judgment on Edgar Rice Burroughs

for his use of the term bawana in his Tarzan stories. The evidence

shows that Burroughs used the term roughly 400 times in 19 Tarzan stories

between 1914-1940. It is also a historical fact that the term bwana was

commonly used by native Africans to address white European travelers and

settlers in British East Africa from 1875 until the end of British colonial

power in the 1960s. The question here if whether or not Burroughs’ created

a misconception by using the term “almost exclusively by subordinate

Africans when addressing Caucasian men,” as the Wikipedia entry

on the term claims.

“Because of such usage,” Wikipedia asserts in reference

to Burroughs’ fiction, “many audiences have taken the word to have a

strong pejorative meaning, along the lines of ‘master,’ ‘massa’ or ‘Great

White Hunter,’ as in the film Call Me Bwana. Such an interpretation stands

in contrast to the original usage of the word, however.”

Putting Burroughs’ usage aside for a moment, there seems

to be evidence that the term bwana actually had a “strong pejorative

meaning” of black subordination to whites in the colonial period, something

which the Wikipedia entry would deny. The following passage from

James Lawrence’s The Rise and Fall of the British Empire indicates

that many white landowners in British East Africa did, in fact, view their

relationship with native Africans in master-servant terms, and that being

addressed as “Bwana” was an integral part of that relationship.

“We’ve been thoroughly betrayed by a lousy British

government,” complained one Kenyan farmer in 1962 … He had first come

to the country in 1938, secured a 999-year lease on his crown land farm,

and had been officially encouraged to see himself as part-squire part-schoolmaster

when dealing with the blacks. “I’m not a missionary; I hate the sight

of the bastards. But I came here to farm, and look after these fellows.

They look up to you as their mother and father; they come to you with their

trials and tribulations.” Now, Kenya’s future prime minister and president,

Kenyatta, was saying that any white Kenyan who still wanted “to be called

‘Bwana’ should pack up and go.” This form of address, and the deference

it implied, mattered greatly to some; Kenya’s white population fell from

60,000 in 1959 to 41,000 in 1965.

During that portion of the British colonial period when

Burroughs was writing, then, the term bwana did indicate a subordinate

role for blacks in the minds of many landholding whites, among whom Burroughs’

Lord Greystoke could be portrayed by critics as a typical example.

The “Bwana” Case Goes

to the Jury

Returning to the question at hand,

though, did Burroughs’ use of bwana in his fiction exaggerate and place

unwarranted emphasis on the deference blacks were expected to display toward

whites during the first half of the twentieth century? A close look at

how Burroughs actually used the term suggests the answer is no.

Of the author’s roughly 400 uses of the term in his Tarzan

stories, about 135 were used as part of a plot device to conceal the identities

of Tarzan and Jessie Jerome in The Son of Tarzan and Tarzan

and the Leopard Men respectively. Another hundred or so times Burroughs

had Waziri tribal members refer to Tarzan, their king, as “Bwana.”

Most of the remaining usages of the term in Burroughs’ fiction relate to

the safari system, in which retained black porters and askaris addressed

their white employers as “bwana.” On only a handful of occasions

can Burroughs’ use of the term legitimately be interpreted as a condescending

expression on the part of African natives to whites.

Those critics intent on building a case of racism against

Edgar Rice Burroughs, then, must look for some other line of attack. The

“bwana” indictment collapses under close inspection. In using that

term, the author simply reflected the times in which he lived. It was a

word commonly used in British colonial Africa during Burroughs’ lifetime,

and so he used it in an attempt to inject some realism to his otherwise

fantastic Tarzan tales. There is no valid evidence that he misused it or

misinterpreted it. And the charge that Burroughs’ fiction was mainly responsible

for creating a false racial connotation of bwana in Western culture is

simply untrue, as those who take the time to read his Tarzan stories closely

will certainly discover.

![]()

.

. .

.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()