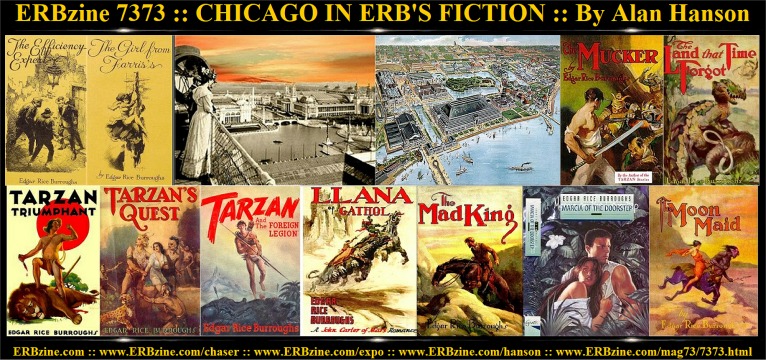

Chicago in ERB’s Fiction

The Fight for Survival in a Corrupt, Immoral City

Part Two

by Alan Hanson

When Burroughs began writing The Efficiency Expert

in

the fall of 1919, his thriving writing career had allowed him to move his

family earlier that year from Chicago to the warmer climate of California’s

San Fernando Valley. Amid a prolonged burst of prolific and financially

productive writing while living in the mid-west, the author had completed

seven Tarzan novels, four Martian novels, two inner world tales, and several

independent novels. After migrating westward, perhaps nostalgia for his

old hometown caused him to take a thirty-day break from adventure writing

that fall to pen a short contemporary novel set almost entirely in Chicago.

When Burroughs began writing The Efficiency Expert

in

the fall of 1919, his thriving writing career had allowed him to move his

family earlier that year from Chicago to the warmer climate of California’s

San Fernando Valley. Amid a prolonged burst of prolific and financially

productive writing while living in the mid-west, the author had completed

seven Tarzan novels, four Martian novels, two inner world tales, and several

independent novels. After migrating westward, perhaps nostalgia for his

old hometown caused him to take a thirty-day break from adventure writing

that fall to pen a short contemporary novel set almost entirely in Chicago.

Early in The Efficiency Expert, protagonist

Jimmy Torrance, a recent college graduate, goes to Chicago expecting to

start a successful career in the business world. He chose that city because

he “always had an idea that was one burg where he could make good,”

and he was “confident that there were many opportunities awaiting him

in Chicago.” (Really, though, in that aspect of the story, there is

nothing particularly Chicagoan about the story told in The Efficiency

Expert. It could have been set in New York, or any number of other

large northeastern or mid-western cities.) Instead of immediate success,

Jimmy experienced the impersonal and harsh realities of life in the big

city. In the end, he survived the school of hard knocks and triumphed with

the help of a career criminal friend and the love of two women.

Choosing Chicago as the backdrop for the story allowed

Burroughs to utilize again his intimate knowledge of the city where he

had lived for four decades. Early in The Efficiency Expert,

the author put Chicago’s population at 3 million. (Census figures set the

city’s population at 2.7 million in 1918.) Burroughs also noted in the

text that Chicago at that time was “one of the largest cities in the

world, the center of a thriving district of fifty million souls.” (Since

the population of the state of Illinois in 1918 was under 6 ½ million

and that of the entire United States was 103 million, the reference to

“fifty million souls” is puzzling. Perhaps Burroughs was referring

to the population of the entire mid-western sector of the country.)

As in earlier stories The Girl From Farris’s

and The Mucker, the author used the names of many Chicago

streets and boulevards in The Efficiency Expert. Jimmy arrived

in the city by train at the LaSalle Street Station. While waiting for want

ad replies placed at the Tribune office on Madison Street, he lived in

a boarding house on Indiana Avenue near Eighteenth Street. Jimmy pawned

his watch in a shop on the corner of Clark and Van Buren and worked as

a waiter in a restaurant on Wells Street. Eventually he got a job as an

efficiency expert at the International Machine Company on West Superior

Street. One evening he changed a flat tire for a woman on Erie Street.

Another night Jimmy took a Clark Street trolley to meet a friend on the

corner of Clark and North Avenue. Other Chicago streets mentioned in the

story are Elmhurst, St. Charles Road, Ashland Avenue, Michigan Boulevard,

Lake Shore Drive, and Lincoln Parkway.

Burroughs did not neglect Chicago’s most famous street.

He let the reader ride along with society belles Elizabeth Compton and

Harriet Holden as their chauffeur drove them down State Street through

the heart of the city on Christmas Eve. During the holiday season, State

Street, noted Burroughs, “was almost alive with belated Christmas shoppers

… As the car moved slowly northward along the world’s greatest retail street

the girls leaned forward to watch the passing throng through the windows.”

Harriet observed, “Who would ever think of State Street as a fairyland

… Even the people who by daylight are shoddy and care-worn take on an appearance

of romance and gaiety, and the tawdry colored lights are the scintillate

gems of the garden of a fairy prince.”

When Jimmy Torrance met Elizabeth Compton and Harriet

Holden, he thought them the two “best-looking girls” he had seen

in the city. That prompted him to conclude, “whether one likes Chicago

or not he’s got to admit that there are more pretty girls here than in

any other city in the country.”

Jimmy arrived in Chicago on a hot July day in 1915, and

his misadventures in the city extended into the summer of the following

year. Whether intentionally or by accident, Burroughs placed the story’s

events in the 1915-16 period. The text states that Jimmy’s boxing encounter

with “Young Brophy” took place on “Saturday, the 15th of January.”

Burroughs wrote the story in 1919, but the closest year that meets that

day/date combination he stated is 1916.

Also helping to date the events in The Efficiency

Expert are references in the story to cases of influenza in Chicago

and to the many theaters operating in the city in those years. Three characters

in the story were stricken with the flu. Mason Compton, Jimmy’s employer

at the International Machine Company, missed some days of work with an

apparently minor affliction, but Jimmy’s case was severe.

“Jimmy Torrance collapsed at his desk. The flu had

struck him as suddenly and as unexpectedly as it had attacked many of its

victims … half an hour later Jimmy Torrance was in a small private hospital

in Park Avenue … For four or five days Jimmy was a pretty sick man. He

was allowed to see no one … At Compton’s orders he had been placed in a

private room and given a special nurse … who was instructed to call Compton

twice a day and report the patient’s condition.”

Jimmy survived his bout with influenza, but his friend,

Edith Hudson, did not. She had helped Jimmy get his job as an “efficiency

expert,” and was at his side in the hospital during his illness. Her

“mothering tenderness,” Burroughs noted, “doubtless aided materially

in his rapid convalescence.” Later, though, Jimmy learned Edith was

“confined to her room with a bad cold.” It was probably influenza,

though, as she faded and died of pneumonia in her north side apartment

with Jimmy at her side.

The presence of influenza cases in The Efficiency

Expert suggests that Burroughs might have intended that the story

took place during Chicago’s influenza epidemic of 1918. The contagion first

hit the city on September 8, 1918, when sailors at the Great Lakes Naval

Training Station fell ill. By the end of the month, it was apparent that

influenza was sweeping through the city. By mid-November, 38,000 cases

of influenza and 13,000 of its lethal offshoot, pneumonia, had been reported

in Chicago. The epidemic was finally declared under control in January

1919. Burroughs, whose family lived through outbreak in Oak Park, began

writing The Efficiency Expert eight months later.

During the height of the influenza danger, all theaters

and movie houses in the city were ordered closed for an indefinite period.

That several such public entertainment venues were open in The Efficiency

Expert indicates that the story took place prior to the 1918 epidemic.

Additionally, while most of the city’s restaurants were deserted during

the outbreak, customers of all classes of society crowded Feinheimer’s

Cabaret in The Efficiency Expert.

Police Oppression

In The Efficiency Expert,

Chicago’s police officers were again portrayed as a heavy-handed lot who

used the law as a weapon to hassle disadvantaged citizens and settle scores

with personal enemies. In the story, Officer O’Donnell is fashioned from

the same mold as Officer Doarty in The Girl From Farris’s.

When Jimmy declined to press charges after a stranger tried to pick his

pocket, O’Donnell nevertheless “turned roughly upon the offender, shook

him viciously a few times, and then gave him a mighty shove which all but

sent him sprawling into the gutter. ‘G’wan wid yez,’ he yelled after him,

‘and if I see ye on this beat again, I’ll run yez in.’” The pickpocket,

identified only as “The Lizard,” later told Jimmy that, “O’Donnell

has been trying to get something on me for the last year. He’s got it in

for me.” Later in court, “The Lizard” testified, “for a while

I was afraid to say anything because this guy O’Donnell has it in for me,

and I knew enough about police methods to know that they could frame up

a

good case of murder against me.”

The officer also had it in for another one of Jimmy’s

friends. “Little Eva,” a lady of the evening in Chicago, told Jimmy

of O’Donnell, “He’s got it in for everybody. That’s what being a policeman

does to a man. Say, most of these guys hate themselves.”

From “The Lizard” and “Little Eva,” Jimmy

learned it was not wise to trust a Chicago cop. They “impressed upon

Jimmy the fact that whatever knowledge a policeman might have regarding

one was always acquired with the idea that eventually it might be used

against the person to whom it pertained.” So, after Jimmy thumped two

homicidal assailants outside of his apartment house one night, even though

he was an innocent victim, he did not report the assault to the police.

Labor Struggles

In The Efficiency Expert,

Burroughs provided some glimpses into the labor struggles that afflicted

American cities like Chicago in the early decades of the twentieth century.

Hired to improve efficiency in the International Machine Company, Jimmy

soon earned the cooperation of the shop’s workers. “I showed them how

they could turn out more work and make more money by my plan,” he explained

to the company’s owner. “This appealed to the piece-workers. I demonstrated

to the others that the right way is the easiest way — I showed them how

they could earn their wages with less efforts.”

However, the animosity of a powerful union boss and a

disgruntled worker conspired to torpedo Jimmy’s efforts. While waiting

on tables during an earlier job at Feinheimer’s, Jimmy defended two women

from the unwanted advances of Steve Murray, a vulgar but powerful labor

leader. To get revenge for the thrashing Jimmy gave him, Murray conspired

with Pete Krovac, an IMC shop employee, to get Jimmy fired. Burroughs described

Krovac as “a rat-faced little foreigner, looked upon among the men as

a trouble-maker. He nursed a perpetual grievance against his employer and

his job, and whenever the opportunity presented … he endeavored to inoculate

others with his dissatisfaction.” While Krovac tried to spread dissention

among the workers, Murray sent a phony threatening letter signed by the

I.W.W. (International Workers of the Word) to the company owner. The labor

leader hatched a plan to rob the company safe and frame Jimmy for the crime.

The truth finally came out when Murray testified under oath at Jimmy’s

trial.

Disadvantaged Neighborhoods

When using Chicago as a setting in

his fiction, Burroughs often focused on the city’s disadvantaged neighborhoods

and their underprivileged inhabitants. In The Efficiency Expert,

though, the author also provided a glimpse of the lavish lifestyle of Chicago’s

affluent class in the early twentieth century. In one of his early menial

jobs in Chicago, Jimmy was able to observe the estate of Mason Compton,

his future employer, while making a milk delivery to an address on Lake

Shore Drive:

“Driving up the alley Jimmy stopped in the rear of

a large and pretentious home, and entering through a gateway in a high

stone wall he saw that the walk to the rear entrance bordered a very delightful

garden. He realized what a wonderfully pretty little spot it must be in

the summer time, with its pool and fountain and tree-shaded benches, its

vine-covered walls and artistically arranged shrubs … On the alley in one

corner of the property stood a garage and stable, in which Jimmy could

see men working upon the owner’s cars and about the boxstalls of his saddle

horses.”

Compton’s daughter, Elizabeth, and her fellow upper crust

friend, Harriet Holden, travelled about town in a chauffeured limousine.

Their fathers were members of the country club. In conversations between

the two debutants, varying condescending and progressive attitudes toward

the city’s poorer citizens are shown to exist in Chicago’s high society

circles. At a time when both girls believed Jimmy Torrance to be of a lower

class, their assessments of him differed.

“He is like many of his class,” replied Elizabeth,

“probably entirely without ambition and with no desire to work any too

hard or to assume additional responsibilities.”

“I don’t believe it,” retorted Harriet. “Unless I am

greatly mistaken, that man is a gentleman. Everything about him indicates

it; his inflection even is that of a well-bred man.”

“How utterly silly,” exclaimed Elizabeth. “I venture

to say that in a fifteen-minute conversation he would commit more horrible

crimes against the king’s English than even that new stable-boy of yours.”

Although neither woman knew it at the time, Jimmy Torrance

came from the same comfortable walk of life as they did. He was raised

in Beatrice, Nebraska, where his father was the president and general manager

of Beatrice Cornmills, Incorporated. During his struggle to make it on

his own in Chicago after college, Jimmy experienced firsthand the difficulties

life presents to the working class in a big city. His two closest friends

during those desperate months of poverty were a career thief and a woman

of the evening. In the closing pages of The Efficiency Expert,

Jimmy is on the verge of resuming his upper class lifestyle by marrying

socialite Harriet Holden and taking the helm of the International Machine

Company. However, during his year of living as one of Chicago’s disadvantaged

people, he came to understand and honor the morality of many in society’s

lower strata, even its criminal element. The “Lizard” was his teacher

—

“I don’t know much about morality, but when it comes

right down to a question of morals I believe my trade is just as decent

as that of a lot of these birds you see rolling up and down Mich Boul in

their limousines.”

Chicago in Other Stories

Burroughs used Chicago as a setting

in one other story he wrote in 1919, but it wasn’t the Chicago he personally

knew or ever would know. More on that Chicago later. For now, it only needs

to be noted that after Burroughs completed writing The Efficiency

Expert in October 1919, he never again used contemporary Chicago

as a setting in any of his stories. He did, however, include many references

to that city in his fiction over the next three decades.

For instance, four prominent characters in other Burroughs

stories were natives of Chicago. The first was Brady, a seaman on the English

tug sunk by a German U-boat in The Land That Time Forgot.

With his fellow survivors, he shared adventures in Caspak. Before going

to sea, Brady had served three years on the “traffic-squad of the Chicago

police force,” the same force Burroughs portrayed as being corrupt

in The Girl From Farris’s, The Mucker, and

The

Efficiency Expert. Brady, however, is a likable and brave character

in The Land That Time Forgot. His mates listened attentively

to his “description of traffic congestion at the Rush Street bridge

during the rush hour,” and he also spoke about “a woman murdered

over on the prairie near Brighton — her throat was cut from ear to ear.”

Burroughs noted that, “Brady was a brave man. He had groped his way

up narrow tenement stairs and taken an armed maniac from a dark room without

turning a hair.” So, not all Chicago cops were corrupt in Burroughs’

stories.

The next conspicuous Chicago citizen to appear in a Burroughs

story was Danny “Gunner” Patrick in 1931’s Tarzan Triumphant.

Danny grew up in the neighborhood south of Madison Street in physical and

social environments much like that those that had warped the youthful Billy

Byrne.

“The ‘Gunner’ had known naught but the squalid aspects

of scenery defiled by man, of horizons grotesque with screaming atrocities

of architecture, of an earth hidden by concrete and asphaltum and littered

with tin cans and garbage, his associates, in all walks of life, activated

by grand and petty meannesses unknown to any but mankind.”

Like Billy Byrne, Danny slid naturally into a life of

crime, though at a much grander and dangerous level than did the “mucker.”

“[Danny] had never been a Big shot, and if he had been

content to remain more or less obscure he might have gone along about his

business for some time until there arrived the allotted moment when, like

many of his late friends and acquaintances, he should be elected to stop

his quota of machine gun bullets; but Danny Patrick was ambitious. For

years he had been the right hand, and that means the pistol hand, of a

Big Shot. He had seen his patron grow rich — ‘lousy rich,’ according to

Danny’s notion — and he had become envious.”

When things got too hot for Billy Byrne in Chicago, he

headed west to San Francisco. “Gunner” Patrick fled the other direction,

eventually winding up in Africa. There he and Tarzan struck a seemingly

unlikely friendship. But Burroughs explained, “Each … was self-reliant,

each was a law unto himself in his own environment; but there the similarity

ceased for the extremes of environment had produced psychological extremes

as remotely separated as the poles.” Raised in the squalor of an urban

slum, Danny was ignorant and bigoted to the core. Tarzan, on the other

hand, having spent his youth amid nature’s inspiring beauty, was guided

by a lofty, innate sense of morality. To Burroughs there was common ground

in that each was a victor in the fight for survival of the fittest. That

natural law existed in Chicago’s slums as surely as it did in Tarzan’s

Africa.

Neal Brown was the next Chicago resident to appear in

a Burroughs story. In 1934’s Tarzan’s Quest, Brown piloted

the plane that crash-landed in the wilds of Africa with Jane and others

aboard. Brown told Lady Greystoke, “My best friends call me ‘Chi,’ …

It’s short for the name of the town I come from — Chicago.” Burroughs

revealed nothing concerning Brown’s background in Chicago, but his profession

as a pilot makes it unlikely he was the product of the city’s slums, like

Billy Byrne and Danny Patrick. Still, Brown was an aggressive character

in Tarzan’s Quest. He was ready to dispense lethal justice

to Prince Sborov when Brown thought him guilty of murder.

Perhaps the most loveable of Burroughs’ many fictional

citizens of Chicago was the last one the author created — S/Sgt. Tony “Shrimp”

Rosetti, a crew member on the American bomber that crashed in the wilds

of Sumatra in Tarzan and “The Foreign Legion.” Burroughs

let Captain Jerry Lucas, the pilot of The Lovely Lady, describe how Rosetti’s

youth in Chicago mirrored that of Billy Byrne and Danny Patrick.

“Shrimp never had much of a chance to learn anything.

His father was killed in Cicero in a gang war when he was a kid, and I

guess his mother was just a gangland moll. She never had any use for Shrimp,

nor he for her. But with a background like that, you’ve got to hand it

to the kid. He didn’t get much schooling, but he kept straight.”

Tony spoke in the same English dialect as Billy Byrne.

In “Foreign Legion,” Captain Lucas explained, “Rosetti

doesn’t speak American — just Chicagoese.” Shrimp used that language

to explain to his fellow aviators a future unintended consequence of training

American soldiers in the art of killing during World War II.

“Wit all de different ways of killin’ and maimin’ wot

we’ve learnt, like sneakin’ up behind a guy an’ cuttin’ his throat or garrotin’

him an’ a lot of worse t’ings than dat even, they’s goin’ to be a lot of

bozos startin’ Murder Incorporateds all over de U.S., take it from me.

I knows dem guys. I didn’t live all my life in Chi fer nuttin’.”

Although he had to fight for survival growing up in Chicago

slums, Tony Rosetti, again like Billy Byrne, retained a love for his hometown.

“God sure made Chi,” he declared. “Geeze! I wisht I was in dear

ol’ Chi right now. Why, de steepest hill dere is de approach to de Madison

Street Bridge … I t’ink I’ll practice up, an’ w’en I gets home I goes out

to Garfield Park and swings t’rough de trees some Sunday w’en dey’s a gang

dere.”

Billy Byrne, Danny Patrick, and Tony Rosetti were Burroughs

characters all cut from the same cloth. They all survived upbringings in

brutal conditions of crime infested Chicago neighborhoods in the twenties

and thirties. Some of the violent skills they learned in their youths allowed

them to live constructive lives after leaving the city. All of them retained

affection for their hometown. Billy Byrne went back to Chicago, only to

learn the city didn’t like him as much as he liked it. Tony Rosetti looked

forward to going back home after the war. Danny Patrick, though, knew returning

to Chicago would be decidedly unhealthy for him, so after his adventures

in Africa, he planned to open a garage and gas station in California.

Observations on Chicago

A variety of other passages relating

to Chicago appear in other Burroughs stories. For instance, in one of his

last stories, Llana of Gathol, the author noted that, “in

most modern Martian cities … assassins’ guilds flourish openly, and their

members swagger through the streets like gangsters once did in Chicago.”

Most of the Burroughs characters connected with Chicago

were natives of that city. Barney Custer was an exception. In The

Mad King, Barney, from Beatrice, Nebraska, was just passing through

Chicago on his way to New York when he remembered something he saw there

during a previous visit to the mid-western metropolis.

“Presently he recalled a scene he had witnessed on

State Street in Chicago several years before — a crowd standing before

the window of a jeweler’s shop inspecting a neat little hole that a thief

had cut in the glass with a diamond and through which he had inserted his

hand and brought forth several hundred dollars worth of loot.”

Then, in Marcia of the Doorstep, Della Maxwell,

another outsider, disliked Chicago so much that she broke her acting engagement

there and returned to her hometown city of New York. “I couldn’t stand

it anymore,” she said of Chicago. “It’s a hick town, filled with

coal dust, wind and tank town talent. And slow, say, if I’d smoked a cigarette

on the street I’d a been pinched for sure.”

Chicago of the Future

In 1919, at the height of the post-war

anti-communist scare in the United States, Edgar Rice Burroughs wrote a

politically charged story titled Under the Red Flag. Setting the

story 200 years in the future, Burroughs’s obvious intention was to present

his vision of how the country would descend into barbarism if communists

were to take hold of the American political system. Unable to sell the

story, Burroughs later revised Under the Red Flag to make it the

middle portion of The Moon Maid trilogy. Instead of communists,

the tyrannical leaders of the country became the descendants of invaders

from the Moon. However, the originally intended communist alarm clearly

remained. (Burroughs termed each political region a “Teivos,” which,

of course, is “Soviet” spelled backwards.)

Burroughs made Julian 9th the narrator of his revised

story in The Moon Maid. “I was born in the Teivos of Chicago

on January 1st, 2100,” he stated. And so Burroughs again used the city

he knew best as the backdrop for his vision of a future America ruled by

despotism. Julian 9th described the ruins of a once great city.

“The first twenty years of my life were uneventful.

As a boy I played among the crumbling ruins of what must once have been

a magnificent city. Pillaged, looted and burned half a hundred times Chicago

still reared the skeletons of some mighty edifices above the ashes of her

former greatness.”

Just two months before he wrote Under the Red Flag,

Burroughs had moved his family to California. Either then, or later when

he rewrote the story, the author included the following detailed reference

to the Chicago suburb where he had lived. Julian 9th’ told the story of

Juana, who was to become his wife.

“She told me that she had been born and raised in the

Teivos just west of Chicago, which extended along the Desplaines River

and embraced a considerable area of unpopulated country and scattered farms.

‘My father’s home is in a district called Oak Park,’

she said, ‘and our house was one of the few that remained from ancient

times. It was of solid concrete and stood upon the corner of two roads

— once it must have been a very beautiful place, and even time and war

have been unable entirely to erase its charm. Three great poplar trees

rose to the north of it beside the ruins of what my father said was once

a place were motor cars were kept by the long dead owner. To the south

of the house were many roses, growing wild and luxuriant, while the concrete

walls, from which the plaster had fallen in great patches, were almost

entirely concealed by the clinging ivy that reached to the very eaves.’”

(Here Burroughs may well have been describing one of

the homes he and his family occupied while living in Oak Park from 1914

until the moved to California in early 1919.)

ERB Chicago Conclusions

Even as he foretold the “crumbling

ruins” of his hometown in the distant future, Edgar Rice Burroughs

looked back on Chicago’s “former greatness” as a “magnificent

city.” Despite focusing on Chicago’s slum neighborhoods as the backdrop

for several of his stories, it’s obvious that Burroughs had fond memories

of his youth in the city. The detailed language with which he described

the streets, buildings, and institutions of Chicago reveal the close relationship

he had with the city of his birth. The cold Chicago winters eventually

drove him away, but the memory of the struggles of its people, with their

transgressions and triumphs, remained clear and memorable in him.

In his fiction, Burroughs was just as disparaging with

Los Angeles, the other metropolis he lived near for many years. Of the

two great cities, though, in his fiction, at least, Chicago is the one

portrayed with the greater character. Chicago breathed with teeming life

under Burroughs’s pen, while Los Angeles came across as a cesspool intent

on consuming itself. In Edgar Rice Burroughs version of “A Tale of Two

Cities,” Chicago was his London and Los Angeles was his Paris.

—The End—

![]()

.

. .

.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()