Chicago in ERB’s Fiction

The Fight for Survival in a Corrupt, Immoral City

Part One

by Alan Hanson

Continued

in Part Two

ERB’s Chicago Years

ERB’s Chicago Years

Edgar Rice Burroughs lived most of

the first half of his life in and around Chicago. He was born in the city

on September 1, 1875, and although he left it occasionally, he always returned

to his hometown before leaving it for good at the age of 44 in 1919. He

attended Chicago public and private schools until the age of 16. He spent

most of the years from 1891 through 1897 away from the city. After a short

stay on his brothers’ ranch in Idaho, he attended Phillips Academy in Massachusetts

and Michigan Military Academy, also serving on staff of the latter school

for a year. During this six-year period of living elsewhere, Burroughs

occasionally returned to Chicago for brief periods. In the summer of 1893,

he drove an electric car in his father’s exhibit at the World Columbian

Exposition in Chicago, and in the summer of 1897, he worked in the

city for the Knickerbocker Ice Company.

Following 10 months of army duty at Fort Grant, Arizona,

he returned to live in Chicago in 1897. While working at the American Battery

Company that summer, he began dating Emma Hulbert. In the spring

of the following year, however, he left Chicago once again to work with

his brothers in Idaho. Within a year, he returned to Chicago and

to employment with the American Battery Company.

After he and Emma were married on January 31, 1901, Burroughs

appeared finally to have settled down in Chicago. But in the spring of

1903, he was off to Idaho again, this time with his young wife in tow.

After a year and a half of struggling to make a living in the Northwest,

the couple returned to Chicago in October 1904.

Burroughs spent the next seven years working a series

of unproductive jobs and operating failing businesses before starting his

writing career in 1911. By the summer of 1913, his ability over the previous

two years to write and sell eight novels for serialization in pulp magazines

convinced him he could make a living writing fiction. With steady work

that could be done anywhere and the cold Chicago winter approaching, Burroughs

took his family to California for six months. After returning to Chicago

in the spring of 1914, he moved his family to the affluent village of Oak

Park, just west of the city. From there Burroughs continued his successful

writing career until 1919, when he left Chicago for a new home in the warm

climate of California’s San Fernando Valley. During the rest of his life,

Burroughs traveled to Chicago only occasionally on business trips and to

visit family members still residing there.

Taking out the short periods he was away for schooling,

army service, adventures in Idaho, and the one winter in California, Edgar

Rice Burroughs lived in Chicago and its environs for about 35 years. It’s

safe to say that he knew Chicago more intimately than any other city he

visited or lived in during his lifetime.

The Girl From Farris’s

Up to that point, the locales in his

published stories — Mars, darkest Africa, the Earth’s core, secluded islands

— had sprung from his imagination. (The only story he had yet to sell was

The

Outlaw of Torn, a historical novel set in thirteenth century England.)

Soon after declaring himself a professional writer, Burroughs

tried his hand at contemporary mainstream fiction for the first time. In

July 1913 he started work on The Girl From Farris’s, a novelette

about the struggles of a young, mid-western country girl suddenly thrown

into a hostile urban environment. As the backdrop for the story, Burroughs

chose the big city he knew best, his hometown of Chicago. His first attempt

at realism did not come easy to him. After starting the story, he set it

aside and worked on five other major stories, before finally finishing

The

Girl From Farris’s in March 1914.

In the story, which appeared as a four-part serial in

All-Story

Weekly in the fall of 1916, the author’s familiarity with Chicago’s

streets and structures is evident. For example, the following passage gives

the reader a detailed itinerary of heroine June Lathrop’s search for lodging

in the city.

“At Lake and Dearborn she stopped to purchase an evening

paper, and in the entrance to a near-by building she sought among the want

ads for a likely boarding-house. She found an address far out on the South

Side, and a moment later boarded a Cottage Grove Avenue car at Wabash Avenue.”

Other Chicago thoroughfares mentioned in the story include

State Street, Twenty-fourth Street, Michigan Avenue, Commonwealth Avenue,

Lake Shore Drive, Jackson Boulevard, Calumet Avenue, and La Salle Street.

In the story’s setting, Burroughs also used then existing city structures,

including the Kenser, Railway Exchange, Criminal Court, and Auditorium

buildings. St. Luke’s hospital, Bridewell Prison, Grant Park, and the Dearborn

Street Bridge are also named, along with the Chicago neighborhoods of Brighton

Park, the Loop, and the South Side levee.

Chicago’s Pervasive Corruption

More significant than his knowledge

of Chicago landmarks in The Girl From Farris’s, though, is

how Burroughs portrayed the corrupt nature of the governing, commercial,

and private groups then interacting in his hometown. In the story, their

conflicting self-interests effectively perpetuate a system that fails to

protect and serve the city’s citizens. It started with the police, who

are portrayed as being routinely “on the take.” In Burroughs’s words,

the officers exercised their “right to certain little incidental emoluments

upon which time-honored custom had placed the seal of lawful title.”

Proprietors who failed to “come across” faced personal reprisals

from beat cops and the loss of their business licenses. Ordinary citizens

who didn’t cooperate with police vendettas faced arrest on trumped up charges.

The legal system is depicted as equally corrupt. The city

prosecutor “pigeonholed” police complaints, and the State Attorney’s

office “bamboozled” grand juries into believing the city’s purveyors

of vice had not broken the law. Abe Farris, owner of the city’s most well

known red light establishment, bragged, “There ain’t nobody that can’t

be made to want to do anything on earth if you can find the way to get

’em where they live.” (Translation: bribery.) The State Attorney spoke

out publicly against vice, but having his eye on the governorship, he wasn’t

about to upset Chicago business owners who feared their property values

would decline if the city’s bordellos were shut down.

Still, it was “a time when public opinion was aroused

by the vice question,” leading to the rise of high-profile reformers

who sought publicity in their efforts to close down the city’s red light

district and convince the wayward women who worked there to give up the

evil lives they were leading. For reformers like Rev. Theodore Pursen,

though, drawing attention to himself in the daily newspapers was more important

than helping the red-light girls find different employment. He explained:

“I abhor as much as any human being can the necessity

which compels so much publicity in these matters, but it is for the greatest

good of the greatest numbers that I labor … If the public does not know

of the terrible conditions which prevail under they very noses, how can

we expect it to rouse itself and take action against these conditions?

We must keep the horrors of the underworld constantly before the voters

and tax-payers until they rise and demand that the festering sore in the

very heart of their magnificent city be cured forever.”

In reality, all the Reverend did for the “depraved”

women of the South levee district was publicly shame them and offer lectures

at the weekly meetings of his “Society for the Uplift of Erring Women.”

Chicago’s newspapers were complicit in the city’s pervasive

corruption. One day they printed Reverend Pursen’s criticism of the police

for not cracking down on vice; the next day an editorial would caution

the State attorney to go slow on reform. “No mention of property values,”

Burroughs explained, “but owners of the newspaper owned nearly a third

of

the real estate in the [red-light] district.”

Another example of how the Chicago press catered to the

city’s business interests occurred following the sudden death of a prominent

businessman in Abe Farris’s brothel:

“They say his family routed the advertising manager

of every paper in the city out of bed at one o’clock in the morning, and

that three morning papers had to pull out the story after they had gone

to press with it, and stick in a column obituary tellin’ all about what

he had done for his city and his fellow man, with a cut of his mug in place

of the front page cartoon.”

Abuses of an Uncaring

City

So what happened when June Lathrop,

a naïve, young farm girl, was lured to the big city by the false promises

of a licentious Chicago businessman? After the wolf dropped dead in the

South Side flophouse where he was keeping June, Abe Farris, “the most

notorious dive keeper in the city,” tried to force her into prostitution.

When June tried to escape, she was “pinched” by Officer Doarty,

who threatened to charge her with murder if she didn’t testify that Farris

held her against her will. During the two weeks the State attorney held

June in jail awaiting her grand jury testimony, Reverend Pursen showed

up at the jail with three newspaper reporters to splash June’s shame across

their front pages. (She told the phony reformer to “beat it.”)

Later, the forces controlling Chicago’s establishment

combined to put June on trial for the murder of the wealthy businessman

responsible for bringing her to the city in the first place. “How the

case had come to be revived no one seemed able to explain,” Burroughs

noted. “A scarehead morning newspaper had used it as an example of the

immunity from punishment enjoyed by the powers of the underworld — showing

how murder, even, might be perpetrated with perfect safety to the murderer.

It hinted at police indifference — even at police complicity.” The

police responded by charging June with a crime of which they knew she was

innocent.

In the end, despite the efforts of the Chicago establishment

to prevent it, June became the kind of girl she wanted to be. She achieved

it, though, not with the assistance of the city’s police, reformers, or

politicians, but through her own efforts and the help of two men who truly

cared about her. In the closing pages of The Girl From Farris’s,

Burroughs summarized how the powers that ruled Chicago in the “Gilded

Age” had nearly destroyed the reputation of an innocent and harmless

citizen.

“The jury was out but 15 minutes, returning a verdict

of not guilty. To June it meant nothing. It was what she had expected;

but though it freed her from an unjust charge, it could never right the

hideous wrong that had been done her, first by an individual in conceiving

and perpetrating the wrong, and then by the community, as represented by

the police, in dragging the whole hideous fabric of her shame before the

world.”

The conclusion of The Girl From Farris’s leaves

June Lathrop in Chicago. Considering how the city treated her, though,

it seems likely she would have left its environs as soon as possible. In

fact, Burroughs disparaged his hometown continually throughout the story.

About the only positive comment about Chicago to be found in The

Girl From Farris’s is an observation by female protagonist June

Lathrop:

“Since her entrance into the world of business the

girl had learned that the great majority of office men accord the same

respect to their female coworkers as they do to their own sisters. That

there were exceptions she had also discovered.”

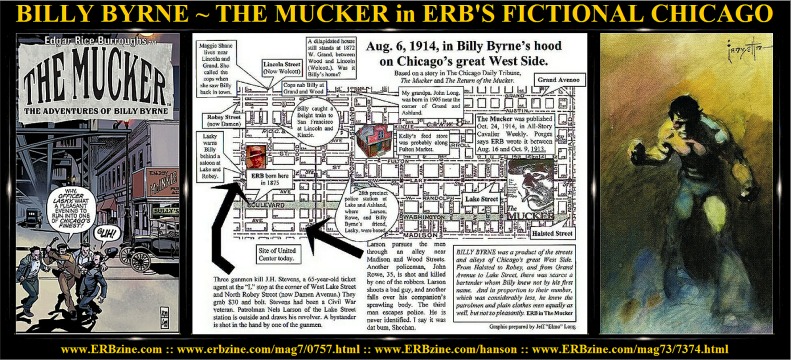

The Mucker

Before he finished The Girl From

Farris’s, Burroughs began writing another story based on the seamy

side of contemporary life in his hometown of Chicago. The first part of

The

Mucker was written in the fall of 1913, and the concluding segment

composed in the opening months of 1916. Although only the opening chapter

of each part is set in Chicago, the influence of the city is paramount

throughout the story. The opening sentence of The Mucker

announces that, “Billy Byrne was a product of the streets and alleys

of Chicago’s great West Side.” The story chronicles his struggles to

rise above the criminal and immoral stains that the city inflicted on his

impressionable character as a youth. Burroughs scattered references to

Chicago throughout as Billy drifted to San Francisco, the Pacific South

Seas, New York City, Kansas City, El Paso, and into revolutionary Mexico.

In describing the neighborhood in which Billy was raised,

Burroughs again utilized his intimate knowledge of Chicago streets and

landmarks. The boundaries of the West Side slum were “from Halsted to

Robey and from Grand Avenue to Lake Street.” Of the area’s main squalid

thoroughfare, Burroughs noted, “there is not much upon either side or

down the center of long and tortuous Grand Avenue to arouse enthusiasm.”

He described structures with long flights of stairs, “which lean precariously

against the scarred face” of frame residences, in which families are

crowded into “ill-smelling rooms.” For the author, one particular

adjective seemed to sum up life along Grand Avenue: “The frowsy (dingy

and stuffy) street [was] filled with frowsy women and frowsy children …

street cars rumbled by with their frowsy loads.”

Burroughs portrayed the city, in general, as an unhealthy

place to live. On one occasion, Billy “filled his deep lungs with the

familiar medium which is known as air in Chicago.” And on another,

he “entered an ‘L’ coach and leaning on the sill of an open window watched

grimy Chicago rattle past.” However, the social pollution of the West

Side slum was far more dangerous than the environmental brand.

Billy Learned to Hate

Women

Billy spent his childhood in a “tumble-down

cottage” in that gloomy neighborhood. No mention is ever made of his father,

just a mother whose treatment of her son was to have dreadful consequences.

“Billy’s mother, always foul-mouth and quarrelsome,

had been a veritable demon when drunk, and drunk she had been whenever

she could, by hook or crook, raise the price of whiskey. Never, to Billy’s

recollection, had she spoken a word of endearment to him; and so terribly

had she abused him that even while he was yet a little boy, scarce out

of babyhood, he had learned to view her with a hatred as deep-rooted as

is the affection of most little children for their mothers.

“When he had come to man’s estate he had defended himself

from the woman’s brutal assaults as he would have defended himself from

another man—when she had struck, Billy had struck back; the only thing

to his credit being that he never had struck her except in self-defense.

Chastity in woman was to him a thing to joke of—he did not believe that

it existed; for he judged other women by the one he knew best—his mother.

And as he hated her, so he hated them all.”

When Billy returned to his old neighborhood in mid-novel,

he was unmoved to learn of his mother’s death. “He owed her nothing

but for kicks and cuffs received, and for the surroundings and influences

that had started him upon a life of crime at an age when most boys are

just entering grammar school.”

Years later, Billy reflected on his childhood in Chicago:

“You have no idea how I was raised … it does make it seem a wonder that

I ever could have made a start even at being decent. I never was well acquainted

with any human being that wasn’t a thief, or a pickpocket, or a murderer

— and they were all beasts each in his own particular way.”

What Burroughs described as Billy’s “kindergarten education”

began in an alley, where a gang of older boys gathered. He was one of a

group of “admiring and envious little boys of the neighborhood who hung,

wide-eyed and thrilled, about these heroes of their childish lives.”

By age six, Billy was “picking up his knowledge of life and the rudiments

of his education” from his “heroes,” all pickpockets, burglars,

and thugs. At age 10, Billy’s education advanced to “swiping” brass

faucets from vacant buildings and selling them to a junkshop owner. At

12 he graduated to robbing freight cars, and earned acceptance to Kelly’s

gang after beating a fellow young ruffian nearly to death.

Billy Accepted Gang’s

Code

Kelly’s gang was one of the older gangs

that claimed “sanctity” over various neighborhoods on Chicago’s

West Side. The congregation of older boys and men assumed the name of the

respectable owner of the feed-store, behind which the gang had gathered

for years. This pack of hoodlums claimed the area from Halsted to Robey

and from Lake to Grand as its own territory. “The police and citizenry

of this great territory were the natural enemies and prey of Kelly’s gang,”

Burroughs noted. “[They] safeguarded the lives and property which they

considered theirs by divine right.” Members of rival gangs crossed

with peril the borders of Kelly’s realm.

Practically born into Kelly’s gang and wholly educated

by it, Billy Byrne wholeheartedly accepted its skewed conventions. “He

knew no other methods; no other code,” Burroughs explained. “Whatever

the meager ethics of his kind he would have lived up to them to the death.

He never had squealed on a pal and he never had left a wounded friend to

fall into the hands of the enemy — the police.”

To the gang, “standards of masculine bravery were strange

and fearful.” Striking from behind and below the belt indicated true

manliness, as did planting a kick in the face of an unconscious man. Seeing

a woman shrink from a threatened blow “appealed greatly to the Kelly-gang

sense of humor.” Billy Byrne learned early to master the hooligan art

of fighting. “I wasn’t as crafty as most of them,” he later recalled,

“so I had to hold my own by brute force, and I did it.” At the young

age of 12, “he commenced to find pleasure in the feel of his fist against

the jaw of his fellow-man.” From that early age, he learned to fight

unfairly, using all the tricks of street fighting — gouging, biting, kicking,

and lowering a concrete paving block on the back of an opponent’s head.

His blows were delivered with incredible power. “Thoroughly aroused,

Billy was a wonder,” Burroughs noted. “From a long line of burly

ancestors he had inherited the physique of a prize bull.”

Scornful of honest work, gang members earned their livings

through various criminal endeavors. When short of money, Billy “would

fare forth in the still watches of the night, with a couple of boon companions

and roll a souse, or stick up a saloon.” Over a two-year period, Billy

“collected what was coming to him from careless and less muscular citizens.

He had helped to stick up a half-dozen saloons. He had robbed the night

men in two elevated stations, and for a while had been upon the pay-roll

of a certain union and done strong arm work in all parts of the city for

twenty-five dollars a week.” Along the way, Billy perfected “the

gentle art of porch-climbing along Ashland Avenue and Washington Boulevard.”

When Kelly’s gang gathered behind the feed-store to share

tales of their stick-ups and brawls, they drank copious amounts of beer

from a tin pail, repeatedly refilled at a nearby saloon. During his years

in the gang, Billy couldn’t leave the booze alone, drinking it regularly

enough to keep him drunk five days out of seven. Alcohol’s effects were

clearly visible in his face. He had a “red, puffy, blotchy” complexion,

and his eyes were “bleary, bloodshot things that had given a bestial

expression to his face.”

Chicago Exported Its Immorality

Edgar Rice Burroughs told the story

of Billy Byrne’s youthful development into a Grand Avenue Chicago hoodlum

in less than seven pages at the beginning of The Mucker.

At the age of 19, Billy, wanted by the police for a murder he did not commit,

hopped a westbound freight out of Chicago. So what kind of man — a product

of the streets of Chicago’s great West Side — did the city thrust upon

an unsuspecting world? For starters, Burroughs noted, “He had left under

a cloud and with a reputation for genuine toughness and rowdyism that has

seen few parallels even in the ungentle district of his birth and upbringing.”

But

he was so much more:

“Billy was a mucker, a hoodlum, a gangster, a thug,

a tough … He was an insulter of girls and women. He was a bar-room brawler,

and a saloon-corner loafer. He was all that was dirty, and mean, and contemptible,

and cowardly in the eyes of a brave man … Billy hated everything that was

respectable. He had hated the smug, self-satisfied merchants of Grand Avenue.

He had writhed in torture at sight of every shiny, purring automobile that

had ever passed him with its load of well-groomed men and women … His idea

of indicating strength and manliness lay in displaying as much of brutality

and uncouthness as possible … All his life had Billy Byrne fed upon excitement

and adventure. As gangster, thug, holdup man and second-story-artist, Billy

had found food for his appetite within the dismal, sooty streets of Chicago’s

great West Side … The West Side had developed only Billy’s basest characteristics.”

Additionally, from childhood he had learned to “deride

and hate” the law, and so when he left Chicago as a young man, he took

with him a defiance of “authority in whatever guise it might be

visited upon him. He hated law and order and discipline.” (As in The

Girl From Farris’s, in The Mucker the Chicago legal

system is portrayed as corrupt, preferring to pin a crime on a pest like

Billy Byrne over the pursuit of real justice.)

Burroughs certainly did not intend to present Billy Byrne

as a typical product of Chicago, or even of its lowly West Side neighborhoods.

Billy is a prototype, a combination of all worst outcomes that heredity,

poverty, and environment in urban slums could generate. Burroughs had Billy

admit that he could have overcome all of the bad cards life had dealt him.

“I could have been decent, though, if I wanted to,” the mucker acknowledged.

“Other fellows who were born and raised near me were decent enough.

They got good jobs and stuck to them, and lived straight; but they made

me sick.”

A Reformed Man Returns

After Billy left Chicago as a young

man, his experiences elsewhere made him realize and regret the depraved

creature his upbringing in the city had made him. But Chicago still beckoned

to him. “He wanted the gang to see that he, Billy Byrne, wasn’t afraid

to be decent,” Burroughs explained. “He wanted some of the neighbors

to realize that he could work steadily and earn an honest living.”

And so he decided to return to the city to start a new, decent life.

“He was standing upon the platform of a New York Central

train that was pulling into the La Salle Street Station, and though the

young man was far from happy something in the nature of content pervaded

his being, for he was coming home. After something more than a year of

world wandering and strange adventure Billy Byrne was coming back to the

great West Side and Grand Avenue.”

He even told heroine Barbara Harding that when his time

came he wanted to die in Chicago. “Grand Avenue for mine, when it comes

to passing in my checks. Gee! But I’d like to hear the rattle of the Lake

Street ‘L,’ and see the dolls coming down the station steps by Skidmore’s

when the crowd comes home from the Loop at night.”

Billy Byrne may have been reformed during his year away

from Chicago, but the city’s civic institutions had not been. The police

nabbed Billy within an hour of his return to Chicago, and he was tried

and convicted by both the city’s press and prosecuting attorney. Perjured

testimony led to a life sentence, and Chicago washed its hands of Billy

Byrne, sending him out of town on a train bound for the penitentiary at

Joliet. He escaped by jumping from the train, and although he was eventually

exonerated of the Chicago murder, he declined to return to his hometown

again, instead choosing to settle in New York after marrying into the affluent

Harding family.

Although Edgar Rice Burroughs left Chicago for the warmer

climate of California’s San Fernando Valley in 1919, he was not through

using his hometown as a setting in his fiction. That first year in California,

he wrote The Efficiency Expert, which chronicles the troubles

young Jimmy Torrance experienced while trying to “make it” in Chicago.

Burroughs’s depiction of the city in that story, along with profiles of

other Chicago characters created by the author, will be examined in part

two of this review of the role Chicago played in ERB’s Fiction.

—

To be continued in Part 2 —

www.ERBzine.com/mag73/7373.html

![]()

.

. .

.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()