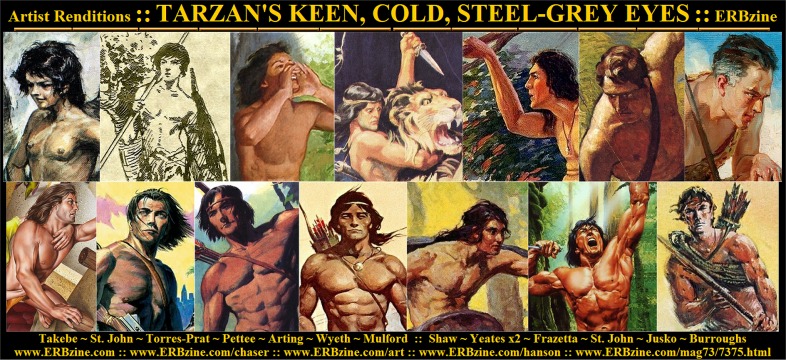

Tarzan’s Keen, Cold, Steel-Gray Eyes

by Alan Hanson

“His eyes and his muscles trained by a lifetime of necessity

moved with the rapidity of light and his brain functioned with an uncanny

celerity that suggested nothing less than prescience.” (Tarzan

the Terrible)

“His eyes and his muscles trained by a lifetime of necessity

moved with the rapidity of light and his brain functioned with an uncanny

celerity that suggested nothing less than prescience.” (Tarzan

the Terrible)

Tarzan of the Apes was a super hero. However, he had no

unique super powers, at least not in the sense of basic abilities normal

human beings do not possess. Instead, his “super power” was that

he, in facing nature at her most basic level, developed all of his human

abilities and senses to the maximum degree possible. From sensory perception

to physical strength to agility to courage and reason, he had no weaknesses.

The building blocks of his super human capabilities were

his extraordinarily enhanced senses. Edgar Rice Burroughs laid that foundation

in his first Tarzan story.

“Man’s survival does not hinge so greatly upon the

perfection of his senses. His power to reason has relieved them of many

of their duties, and so they have, to some extent, atrophied, as have the

muscles which move the ears and scalp, merely from disuse … Not so with

Tarzan of the Apes. From early infancy his survival had depended upon acuteness

of eyesight, hearing, smell, touch, and taste far more than upon the more

slowly developed organ of reason.”

Burroughs provided many examples in his Tarzan saga of

the ape-man using his senses — especially eyesight, smell, and hearing

— in unison. “His eyes, his ears and his keen nostrils were ever on

the alert,” the author noted in Jungle Tales of Tarzan.

In that same volume, Burroughs asserted that Tarzan’s sight was the least

useful of those three senses. As the ape-boy traveled through the jungle,

he depended “even more upon his ears and nose than upon his eyes for

information.” His hearing and sense of smell could reach out far beyond

the visible scene. In particular, Burroughs often stressed the importance

of Tarzan’s sense of smell. “Keener than his keen eyes was that marvelously

trained sense of scent that had first been developed in him during infancy.”

(Tarzan the Terrible)

Ultimately, however, Burroughs acknowledged that sight

was, in fact, Tarzan’s dominant sense. While the ape-man gathered initial

information through scent and sound, he depended on sight for confirmation.

At times, such as in the opening scene of Tarzan and the City of

Gold, the ape-man’s nose and ears were rendered useless. In that

situation, when a band of shiftas approached Tarzan from down wind, he

was unable to smell or hear them. It was only when he turned and saw them,

that he was able to assess his danger. As Burroughs admitted about his

hero in Tarzan’s Quest, “only the things that he had seen

with his own eyes was he sure of.”

Burroughs’ first reference to Tarzan’s eyesight came on

a day when the ape-boy silently dropped into the native village of Mbonga.

“For a moment he stood motionless, his quick, bright eyes scanning the

interior of the palisade.”

The first half of Tarzan of the Apes is

essentially a “coming-of-age” story, and like most adolescents,

Tarzan had issues with his appearance. When he first saw his face reflected

in a placid jungle pool, his repugnant countenance horrified him. “When

he saw his own eyes; ah, that was the final blow — a brown spot, a gray

circle and then blank whiteness. Frightful! not even the snakes had such

hideous eyes as he.” At that age, Tarzan admired the beautiful red-rimmed,

bloodshot eyes of ape playmates.

Gray Eyes with a “savage

glint”

In his Tarzan stories, Burroughs often

referred to Tarzan’s gray eye color, which he occasionally specified as

“steel-gray.” In their relaxed state, his eyes carried a “savage

glint” and a “natural expression of keen intelligence.” Crowning

his eyes was a shock of black hair, which, in his youth, he kept “rudely

bobbed with a rugged bang” in front. “For the appearance of it he

cared nothing,” Burroughs explained, “But in the matter of safety

and comfort it meant everything. A lock of hair failing in one’s eyes at

the wrong moment might mean all the difference between life and death.”

Especially in Tarzan’s youth, Burroughs stressed the natural

intelligence evident in the ape-boy’s eyes. The author drew a picture of

the young Tarzan bending over a book as he sat on a table in his father’s

beach cabin.

“His great shock of long, black hair falling about

his well shaped head and bright, intelligent eyes — Tarzan of the apes,

little primitive man, presented a picture filled, at once, with pathos

and with promise — an allegorical figure of the primordial groping through

the black night of ignorance toward the light of learning.”

Later Burroughs again made the young Tarzan’s “intelligent”

eyes a key ingredient in a physical description of his adolescent ape-man.

“With the noble poise of his handsome head upon those

broad shoulders, and the fire of life and intelligence in those fine, clear

eyes, he might readily have typified some demi-god of a wild and warlike

bygone people of his ancient forest.”

Tarzan’s bright eyes contributed prominently to the overall

majestic impression he created in the sight of others. In Tarzan

the Invincible, the Russian conspirator Zora Drinov was “impressed

by his great physical beauty, as well as by a certain marked nobility of

bearing that harmonized well with the dignity of his poise and the intelligence

of his keen gray eyes.”

As with all of his senses, the acuity of Tarzan’s eyesight

was remarkable. He could discern far-off objects and interpret distant

scenes that other human eyes could not see. “The eyes of Tarzan are

like the eyes of an eagle,” the Waziri chieftain Muviro declared in

Tarzan

the Invincible. Burroughs put those eagle eyes on display in Tarzan

the Untamed. When the vengeful ape-man approached a German battle

line from high above and behind, his ability to see from great distances

gave him an advantage. “His position gave him a bird’s eye view of the

field of battle, and his keen eyesight picked out many details that would

not have been apparent to a man whose every sense was not trained to the

highest point of perfection as were the ape-man’s.”

The term “keen,” used in the passage above to indicate

the sharpness of Tarzan’s vision, was by far the most common modifier Burroughs

used to describe the ape-man’s eyesight. Dozens of references to Tarzan’s

“keen eyes” can be found throughout the author’s stories about the

ape-man from Tarzan of the Apes in 1912 through Tarzan

and “The Foreign Legion” in 1947.

“Nocturnal Visionary Powers”

Burroughs also gave Tarzan a greatly

enhanced ability to see in low-light situations. “He had the gift, that

some men have in common with nocturnal animals,” the author noted in

Tarzan

the Magnificent, “of being able to see in the dark better than

other men.” In Jungle Tales of Tarzan, Burroughs explained

that, “long use of his eyes in the Stygian blackness of the jungle nights

had given the ape-man something of the nocturnal visionary powers of the

wild things with which he had consorted since babyhood.”

In The Return of Tarzan, Burroughs claimed

that, “Tarzan was accustomed to using his eyes in the darkness of the

jungle night, than which there is no more utter darkness this side of the

grave.” However, several incidents in Tarzan stories indicate that

the ape-man could not see in total darkness. Confined in a cell in Opar

in Tarzan and the Golden Lion, the ape-man could see nothing

in the “inky darkness” when the door opened and someone entered

the chamber. Again confined in Opar in Tarzan the Invincible,

his inability to see in complete darkness almost cost him his life.

“He wished that his eyes might penetrate the darkness,

for if he could see the lion as it charged he might be better prepared

to meet it. In the past he had met the charges of other lions, but always

before he had been able to see their swift spring and to elude the sweep

of their might talons as they reared upon their hind legs to seize him.

Now it would be different, and for once in his life, Tarzan of the Apes

felt death was inescapable.”

Even though Tarzan had enhanced vision in the dark, his

human eyes still made him vulnerable in nighttime confrontations with the

great cats. “Tarzan was, to a greater or lesser extent, a nocturnal

beast,” Burroughs explained in Tarzan the Terrible. “It

is true he could not see by night as well as they, but that lack was largely

recompensed for by the keenness of his scent and the highly developed sensitiveness

of his other organs of perception.”

Tarzan was further limited by the time it took for his

vision to become accustomed to dark places. When, as a boy, he first opened

the door of his parents’ cabin, his eyes had to adjust to the dim light

of the interior before he entered. Years later in Pal-ul-don, he found

himself trapped in the Temple of Gryfs in A-lur. “As he stood there

his eyes slowly grew accustomed to the darkness and he became aware that

a dim light was entering the chamber through some opening, though it was

several minutes before he discovered its source.”

After his eyes adjusted to darkness, however, his vision

was as sharp as humanly possible under such conditions. In the temple,

he saw a dark opening, which allowed him to escape a charging Gryf. “Without

hesitation Tarzan plunged into it,” Burroughs noted. “Even here

his eyes, long accustomed to darkness that would have seemed total to you

or to me, saw dimly the floor and the walls within a radius of a few feet.”

Tarzan’s Eyes Snapped

Open

Although heredity must have been a

factor in Tarzan’s extraordinary vision, Burroughs never so credited it.

Instead, the author contended that the ape-man’s eyesight was “brought

to a marvelous state of development by the necessities of his early life,

where survival itself depended almost daily upon the exercise of the keenest

vigilance.” Tarzan’s musculature certainly strengthened as a result

of the environment in which he was raised, and Burroughs seemed to suggest

that an enhanced acuity of the ape-man’s vision also was a byproduct of

his primitive life.

In the following passage from Tarzan the Terrible,

notice how Tarzan’s visual perception operated much faster than that of

normal men.

“Tarzan does not awaken as you and I with the weight

of slumber still upon his eyes and brain, for did the creatures of the

wild awaken thus, their awakenings would be few. As his eyes snapped open,

clear and bright, so, clear and bright upon the nerve centers of his brain,

were registered the various perceptions of all his senses.”

Tarzan’s “keen” vision allowed him to notice and

process the minutest of details in his primitive world. In Tarzan

the Untamed, Burroughs described how a slight movement in the stem

of one leaf apprised Tarzan of a panther in hiding. “It came from pressure

at the bottom of the stem,” the author explained, “which communicates

a different movement of the leaves than does the wind passing among them,

as anyone who has lived his lifetime in the jungle well knows.”

Tarzan’s ability to detect unnatural and menacing motion

was just one aspect of his wider visual awareness of his immediate surroundings.

As Burroughs explained in the opening pages of Tarzan and the City

of Gold, the ape-man’s eyes were continually active.

“He knew every possible avenue of escape within the

radius of his vision for every danger that might reasonably be expected

to confront him here, for it is the business of the creatures of the wild

to know these things if they are to survive.”

Burroughs provided many other instances in which Tarzan’s

vision was critical to his life in the jungle. During physical combat,

for instance, the ape-man’s eyes gave him an advantage over his antagonists.

When preparing to battle a great ape, such as Akut in The Beasts

of Tarzan and Taug in Jungle Tales of Tarzan, the

ape-man’s eyes never left those of his opponent. He read there his adversary’s

plan of attack and reacted accordingly.

It was the same with charging lions. Tarzan watched for

Numa’s swift spring so that he could avoid the cat’s talons as it reared

up to grab him. If the ape-man had time to use his spear on a charging

lion, his vision again played a critical role. “He measured the distance

with a trained eye as the lion started its swift, level charge. Then, when

it was coming at full speed, his spear hand flew back and he launched the

heavy weapon.” (Tarzan and the City of Gold)

When facing beasts, Tarzan usually fought defensively.

Combat with another human in the wild was a different matter for the ape-man.

Since his enemies usually had weapons, such as firearms or arrows, Tarzan

could not approach them openly. Using his eyes and stealthy movements,

he placed himself in an advantageous position to attack, as he did in the

following scene from Tarzan and “The Foreign Legion”.

“Finally he located the sentry and climbed into the

same tree in which had been built the platform on which the man was squatting.

He was poised directly over the fellow’s head. His eyes bored down through

the darkness. They picked out the form and position of the doomed man.

Then Tarzan dove for him headfirst, the knife in his hand.”

On some occasions, though, circumstances dictated that

Tarzan avoid battle altogether, and instead look for an avenue of escape.

His visual attention to detail played a critical role at such times. As

Burroughs noted, “Slow is the mind of man, slower his eyes by comparison

with the eye and the mind of the trapped beast seeking escape.”

When Tarzan found himself trapped in a thipdar nest on

top of a lofty granite rock in Pellucidar, he made a close inspection of

the spire in search of an escape route.

“Lying flat upon his belly he looked over the edge,

and thus moving slowly around the periphery of the lofty aerie he examined

the walls of the spire with minute attention to every detail. Again and

again he crept around the edge until he had catalogued within his memory

every projection and crevice and possible handhold that he could see from

above. Several times he returned to one point and then he removed the coils

of his grass rope from about his shoulders and holding the two ends in

one hand, lowered the loop over the edge of the spire. Carefully he noted

the distance that it descended from the summit.”

Spoors Plain as the Printed

Page

“Stories are not written in books

alone,” Tarzan explained to the Dutch girl Corrie Van der Meer during

their trek across the island of Sumatra. Indeed, to the ape-man the art

of tracking in his primitive environment seemed as easy as reading a book.

The spoors of beasts and men were “as plain to him as type upon a printed

page to you or me,” Burroughs noted.

Scattered throughout the Tarzan stories are many detailed

accounts of his tracking skills. As the example below from Tarzan

of the Apes shows, his keen vision was most helpful at such times,

although Burroughs noted that Tarzan also occasionally checked “his

sense of sight against his sense of smell, that he might more surely keep

on the right trail.”

“For a moment he scrutinized the ground below and the

trees above, until the ape that was in him by virtue of training and environment,

combined with the intelligence that was his by right of birth, told his

wondrous woodcraft the whole story as plainly as though he had seen the

thing happen with his own eyes.

“And then he was gone again into the swaying trees,

following the high-flung spoor which no other human eye could have detected,

much less translated.

“At boughs’ ends, where the anthropoid swings from

one tree to another, there is most to mark the trail, but least to point

the direction of the quarry, for there the pressure is downward always,

toward the small end of the branch, whether the ape be leaving or entering

a tree; but nearer the center of the tree, where the signs of passage are

fainter, the direction is plainly marked.

“Here, on this branch, a caterpillar has been crushed

by the fugitive’s great foot, and Tarzan knows instinctively where that

same foot would touch in the next stride. Here he looks to find a tiny

particle of the demolished larva, oft-times not more than a speck of moisture.

Again, a minute bit of bark has been upturned by the scraping hand, and

the direction of the break indicates the direction of the passage. Or some

great limb, or the stem of the tree itself has been brushed by the hairy

body, and a tiny shred of hair tells him by the direction from which it

is wedged beneath the bark that he is on the right trail.

“Nor does he need to check his speed to catch these

seemingly faint records of the fleeing beast. To Tarzan they stand out

boldly against all the myriad other scars and bruises and signs upon the

leafy way.”

Tarzan even had the ability to follow such trails by night,

but since he found doing so a “slow and arduous method of tracking,”

he usually waited for daylight to make the spoor clearer to his eyes.

Burroughs made several interesting statements concerning

Tarzan’s ability to identify footprints. In Tarzan and the Leopard Men,

he was able to describe four men he was tracking just by looking at impressions

of their feet — “One is old and limps; one is tall and thin; the other

two are young warriors. They step lightly, although one of them is a large

man.”

While examining some native footprints in Tarzan

and the Golden Lion, Tarzan noticed a “smaller one of a white

woman — a loved footprint that he knew as well as you know your mother’s

face.” It was Jane’s, of course.

Finally, in Tarzan the Untamed Burroughs had the

ape-man make a dubious racial observation based on sandal impressions in

the dirt. “It is evident to me,” he judged, “that the foot inside the

sandal that made these imprints was not the foot of a Negro … the impression

of the heel and ball of the foot are well marked even through the sole

of the sandal. The weight comes more nearly in the center of a Negro’s

footprint.”

As for Tarzan’s own footprints, they had a special characteristic.

Some people are said to have eyes in the back of their heads; in Tarzan

the Untamed, Burroughs implied that Tarzan had eyes in his feet.

“Apparently he took no cognizance of where he stepped, yet never a loose

stone was disturbed nor a twig broken — it was as though his feet saw.”

Judging people at first

sight

Tarzan’s eyes absorbed more than the

details of his natural surroundings. His powers of observation also focused

on people, including natives and foreigners, categorizing them as good

or evil for future reference. An affair on the ocean liner in the opening

chapter of The Return of Tarzan demonstrated Tarzan’s ability

to observe and judge people. In the ship’s salon, he noticed the image

of four men playing cards reflected in a mirror. Something suddenly caught

his attention, and from then on no further detail of the scene escaped

him. What he saw and his involvement in foiling the plans of the dastardly

villain Nicholas Rokoff made a lasting impression on Tarzan’s memory. That

enabled him later to identify Rokoff, who was traveling incognito on another

ship. “Tarzan happened to be watching the man at the time, and noticed

the awkward manner in which he handled the chair — the left wrist was stiff.

That clew was sufficient — a sudden train of associated ideas did the rest.”

While Tarzan’s visual memory quickly cataloged villains,

they also were able to make more favorable judgments of other men at first

meeting. For example, in the following passage from Tarzan at the

Earth’s Core, the ape-man assessed the character of an American

he had never seen before.

“Near the head of the column marched a young white

man, and when Tarzan’s eyes had rested upon him for a moment as he swung

along the trail they impressed their stamp of approval of the stranger

within the ape-man’s brain, for in common with many savage beasts and primitive

men Tarzan possessed an uncanny instinct in judging aright the characters

of strangers whom he met.”

The stranger was Jason

Gridley.

Another example of Tarzan judging character

by appearance occurred when he met the noble, Thudos, in Cathne, the City

of Gold. “His was a face that one might trust,” Tarzan observed,

“for integrity, loyalty, and courage had left their imprints plainly

upon it, at least for eyes as observant as those of the lord of the jungle.”

On a few occasions, Burroughs revealed that Tarzan’s eyes

were capable of more than reading spoors, friends, and enemies. The ape-man

also stopped occasionally and used his eyes to appreciate the beauty of

nature in his primeval world. While hunting Horta, the boar, in Tarzan

Triumphant, he paused to view a charming scene.

“Low trees grew in the bottom of the ravine and much underbrush,

for here the earth held its moisture longer than on the ridges that were

more exposed to Kudu’s merciless rays. It was a lovely sylvan glade, nor

did its beauties escape the appreciative eyes of the ape-man.”

Although Burroughs rarely painted such scenes of his ape-man

enjoying the aesthetic allure of nature, in the following passage in Tarzan

the Magnificent, the author revealed that appreciation of nature’s

splendor was an integral ingredient in Tarzan’s savage spirit.

“The beauty of the aspect was not lost upon the ape-man,

whose appreciation of the loveliness or grandeur of nature, undulled by

familiarity, was one of the chiefest sources of his joy of living. In contemplating

the death that he knew must come to him as to all living things his keenest

regret lay in the fact that he would never again be able to look upon the

hills and valleys and forests of his beloved Africa; and so today, as he

lay like a great lion low upon the summit of a hill, stalking his prey,

he was still sensible of the natural beauties that lay spread before him.”

When Tarzan was in Pellucidar, a momentary rapture with

the beauties of that new world nearly cost him his life. The ape-man paused

on a game trail to absorb the new wonders all around him. He marveled at

the great trees with great vines descending and at the beautiful flowers

that bloomed riotously on the ground. Suddenly, a hidden snare encircled

his body and drew him high into the air. “Tarzan of the Apes had nodded,”

explained Burroughs. “His mind occupied with the wonders of his new

world had permitted a momentary relaxation of that habitual wariness that

distinguishes creatures of the wild.”

The Blazing Eyes of a

Beast of Prey

During tranquil moments, intelligence

was the characteristic most evident in Tarzan’s eyes. However, the light

in his eyes often changed, reflecting a wide range of intense emotions

generated by life in the wild. Take, for example, how the look in Tarzan’s

eyes transformed following the passion of battle.

“Tarzan leaped to his feet. For a moment he surveyed

the surrounding warriors with the blazing eyes of a beast of prey at bay

upon its kill; then he placed a foot upon the carcass of the hunting lion,

raised his face to the heavens, and from the great chest rose the challenge

of the bull ape.”

A savage glow in Tarzan’s eyes signaled a sudden rise

in bestial emotion that dominated his psyche until the episode that caused

the regression passed. For example, in the following passage from The

Beasts of Tarzan, the ape-man’s eyes revealed how consuming his

anger could be.

“What were you doing with them — where were you taking

them?” asked Tarzan, and then, fiercely, leaping close to the fellow with

fierce eyes blazing with the passion of hate and vengeance that he had

with difficulty controlled: “What harm did you do to my wife or child?”

Another example Tarzan’s eyes exposing a primitive passion

that nearly overwhelmed his reason occurred in The Return of Tarzan.

“An ugly light gleamed in those gray eyes” as the ape-man aimed

a poisoned arrow at the back of his cousin, William Clayton, the man he

believed stood between him and the woman he loved. Fortunately for all

concerned, that light in his eyes faded before Tarzan let the arrow fly.

Perhaps the most terrible expression to enter Tarzan’s

eyes, however, came when he entered his African bungalow after a German

military raid had occurred there. “The first sight that met his eyes

set the red haze of hate and bloodlust across his vision, for there, crucified

against the wall of the living-room, was Wasimbu, giant son of the faithful

Muviro.”

When Burroughs wanted Tarzan’s eyes to reflect determination,

the author used the descriptor “cold.” The evil Bukawai “saw

death, immediate and terrible, in the cold eyes” of Tarzan, then still

in his teens. Several years later in Paris, Tarzan’s friend Paul D’Arnot

saw something in Tarzan’s “set jaw and the cold, gray eyes” that

made the Frenchman realize that his friend would have trouble adapting

to civilization’s laws. When the conspirator Michael Dorsky threatened

the bound Tarzan with a knife, the ape-man’s only reply was a cold stare.

A minute later, Dorsky was dead. In Tarzan the Magnificent,

the ape-man told the Athnean dictator Phoros, “Quiet, or I kill.”

Looking into those “cold grey eyes” convinced Phoros to start begging

for his life. Finally, when Tarzan found the American adventurer Colin

Randolph, the man who had usurped his name in Tarzan and the Madman,

the ape-man approached the imposter with a cold stare that portended the

American’s immediate death. (He received a last minute reprieve.)

When circumstances caused Tarzan’s anger to mount, his

eyelids often narrowed, indicating that he was assessing the situation

prior to acting. For instance, when Robert Canler insisted that Jane marry

him immediately at the Porter home in Wisconsin, Tarzan “glanced out

of half-closed eyes at Jane Porter, but he did not move.” When the

impatient Canler grabbed Jane’s arm, Tarzan acted, and within seconds Canler

released Jane from her promise to marry him.

Other troubling situations in his later life caused Tarzan’s

eyes to narrow in ire. When police officers in Paris told Tarzan he had

to accompany them to their station, “it was a wild beast that looked

upon them through those narrowed lids and steel-gray eyes.” In Pal-ul-don,

Tarzan’s eyes “narrowed angrily” at the sight of the corpse of new-born

baby that had been sacrificed in the temple of A-lur. When he later came

upon the camp of the conspirators in Tarzan and the Golden Lion,

his eyes narrowed as he demanded to know, “Who are you who dare thus

invade the country of the Waziri, the land of Tarzan?” And when he

was later placed in the arena of Cathne, the City of Gold, to fight for

the amusement of Queen Nemone, he was unafraid but annoyed. “Crowds

irritated his nerves … Through narrowed lids he surveyed the scene. If

ever a wild beast looked upon its enemies it was then.”

While anger was the most common passion to light Tarzan’s

eyes, other, more compassionate emotions were reflected there as well from

time to time. When Meriem first met Tarzan, she noticed a benevolent sentiment

in her savior’s gaze. “Meriem looked straight into the keen gray eyes.

She must have found there an unquestionable assurance of the honorableness

of their owner.” In Tarzan and the Jewels of Opar, the

sound of Tantor’s approach in the distance, “brought a sudden light

of hope to Tarzan’s eyes,” and when Janette Laon cut the bonds from

Tarzan’s discolored and swollen wrists in The Quest of Tarzan,

the mute ape-man “said nothing, but his eyes seemed to thank her.”

Although it was an unusual occurrence in Tarzan’s grim

existence, his eyes occasionally “smiled.” When Tarzan realized

that members of a Hollywood film company had mistaken him for one of their

actors, “the shadow of a smile was momentarily reflected by his grey

eyes.” Later, when Tarzan crossed paths in Los Angles with the movie

star Balza, previously a wild girl he had encountered in Africa, a “suspicion

of a smile” appeared in Tarzan’s eyes.

With a Wink and a Stare

On a couple of occasions, Burroughs

had Tarzan employ a “wink” to communicate silently with another

person. Both came late in the Tarzan series, when the author began to exercise

his ape-man’s sense of humor. The first occurred in Tarzan and the

City of Gold during a recreational hunt in which trained Cathnean

lions were to track down a slave who had been released as quarry. His sense

of fair play incensed, Tarzan, unbeknown to the hunt organizers, had helped

the slave escape. Before the lions were to be set loose, their owners offered

to take bets on the results of the hunt. Tarzan suggested that his friend

Gemnon bet 1,000 drachmas that the slave would escape. Knowing the bet

was a sure thing, Tarzan turned his head toward his friend and “slowly

closed one eye.” Noting Tarzan’s silent assurance, Gemnon made the

bet.

The other instance of the ape-man utilizing a wink to

convey a silent message came in The Quest of Tarzan. Believing

him to be a bestial wild man, Tarzan’s captor had confined him in a cage

along with a young woman captive, expecting that the ape-man would violently

attack her. Instead, Tarzan and the woman conspired to play a joke on their

fellow captives who expected to witness a brutal scene.

“Tarzan looked up at Janette Laon, with a shadowy smile

just touching his lips, and winked. ‘Do you find the captain palatable,’

she asked in English loudly enough to be heard in the adjoining cage.

‘He is not as good as the Swede they gave me last week,’

replied Tarzan.”

Although Tarzan seldom used a wink to communicate, he

got his message across often with a silent, menacing stare. Invariably,

all those upon whom the ape-man fixed his cold eyes withered under his

fierce, implacable gaze. The vile Michael Dorsky was daunted by Tarzan’s

stare, even though the ape-man’s hands were bound. When the Russian addressed

Tarzan, “the captive made no reply, but his eyes never left the other’s

face. So steady was the unblinking gaze that Dorsky became uneasy beneath

it.” And when Phobeg, the Cathnean strongman, threatened to thrash

Tarzan in their cell, “Tarzan turned toward the angry man, his level

gaze fixed upon the other’s eyes, and waited. He said nothing, but his

attitude was an open book that even the stupid Phobeg could read. And Phobeg

hesitated.”

Tarzan’s relentless stare also subdued the fierce Sumatran

native leader, Iskandar, in “Foreign Legion”. When Tarzan

ordered him and his nine warriors to raise their hands in surrender before

he counted to ten, Iskandar gave in at the count of five. “He had looked

into the gray eyes of the giant standing above him and he was afraid …

They are not the eyes of a man, he thought. They are the eyes of a tiger.”

While others often could read Tarzan’s intentions and

emotions in his eyes, the ape-man searched in the eyes of others for clues

to their temperament. This was especially true when he encountered women

during his adventures. Tarzan, in common with most men, often found it

more difficult to understand women than men. In Tarzan and the Ant

Men, the ape-man sought to read what was written in the eyes of

Princess Janzara.

“Tarzan looked into her eyes. They were gray, but the

shadows of her heavy lashes made them appear much darker than they were.

He sought there an index to her character, for here was the young woman

whom his friend, Komodoflorensal, hoped someday to espouse and make queen

of Trohanadalmakus, and for this reason was the ape-man interested.”

It was in Tarzan’s volatile relationship with Queen Nemone

of Cathne, however, that the eyes of both parties played a key role. Both

were watchful when they first met in the City of Gold.

“She kept her eyes upon him as she crossed the room

slowly, and Tarzan did not drop his own from hers. There was neither boldness

nor rudeness in his gaze, perhaps there was not even interest—it was the

noncommittal, cautious appraisal of the wild beast that watches a creature

which it neither fears nor desires.”

Nemone fascinated him, but whether for her beauty or her

malevolence, he did not know at first. On further observation, he decided

it was the former. “Tarzan neither spoke nor moved nor took his eyes

from the eyes of Nemone. Though he had thought her beautiful before, he

realized now that she was even more gorgeous than he had believed it possible

for any woman to be.”

For her part, Nemone was not used to a man who so brazenly

stared her in the eye. It both angered and attracted her. “A hard look

flashed in the Queen’s eyes … Tarzan’s eyes did not leave hers; she saw

amusement in them. ‘Oh, why do I endure it!’ she cried, and with the query

her anger melted.”

When a romantic encounter between the two was interrupted,

Tarzan had to shake himself to break Nemone’s spell. “He drew a palm

across his eyes as one whose vision has been clouded by a mist; then he

drew a deep sigh and moved toward the doorway.”

Tarzan Nearly Lost His

Eyesight

Before closing this study of Tarzan’s

eyes, there are a couple of interesting incidents concerning them that

deserve mention. The first occurred while the young Tarzan was stalking

an enemy in the jungle. While crouching motionless with his eyes on his

prey, a poisonous insect landed on Tarzan’s face. A sting would mean “days

of anguish” to the boy, but he did not move, exercising super-human

restraint

“His glittering eyes remained fixed upon Rabba Kega

after acknowledging the presence of the winged torture by a single glance.

He heard and followed the movements of the insect with his keen ears, and

then he felt it alight upon his forehead. No muscle twitched, for the muscles

of such as he are the servants of the brain. Down across his face crept

the horrid thing — over nose and lips and chin. Upon his throat it paused,

and turning, retraced its steps. Tarzan watched Rabba Kega. Now not even

his eyes moved. So motionless he crouched that only death might counterpart

his movelessness. The insect crawled upward over the nut-brown cheek and

stopped with its antennae brushing the lashes of his lower lid. You or

I would have started back, closing our eyes and striking at the thing;

but you and I are the slaves, not the masters of our nerves. Had the thing

crawled upon the eyeball of the ape-man, it is believable that he could

yet have remained wide-eyed and rigid; but it did not. For a moment it

loitered there close to the lower lid, then it rose and buzzed away.”

On two occasions, Tarzan came close to losing his precious

eyesight. The first came at the hands of the witch doctor Khamis in Tarzan

and the Ant Men. After capturing and binding the hands of Tarzan,

Khamis used a small fire to heat up a couple of irons as he questioned

Tarzan about the disappearance of his daughter, Uhha. When the ape-man

did not respond, the witch doctor seized a red-hot iron, intending to burn

out Tarzan’s right eye. The danger caused the ape-man to exert “terrific

physical force” to snap the bonds on his wrists and save his vision.

Tarzan came much closer to having his eyes burned out

when Woora, the powerful witch doctor of the Zuli tribe in Tarzan

the Magnificent, entrapped him in cord mesh.

“He looked to the iron, muttering and mumbling to himself.

It had grown hot; the point glowed. ‘Take a last look, my guest,’ cackled

Woora, ‘for after a moment you will never again see anything.’ He withdrew

the iron from the coals and approached his prisoner.

“The strands of the net closed snugly about the ape-man,

confining his arms; so that though he could move them, he could move them

neither quickly nor far. He would have difficulty in defending himself

against the glowing point of the iron rod.

“Woora came close and raised the red-hot iron to the

level of Tarzan’s eyes; then he jabbed suddenly at one of them. The victim

warded off the searing point from its intended target. Only his hand was

burned. Again and again Woora jabbed; but always Tarzan succeeded in saving

his eyes, yet at the expense of his hands and forearms.

“‘You pretend that you are not afraid,’ he screamed,

‘but I’ll make you shriek for mercy yet. First the right eye!’ And he came

forward again, holding the red point on a level with the ape-man’s eyes.”

Tarzan was not able to free himself from the mesh, and

Woora probably would have accomplished his goal eventually, had not a friend

of the ape-man entered the room to kill Woora and release the Tarzan.

In All That He Saw, He

Read a Story

An array of emotions shone in the eyes

of Tarzan of the Apes during his life, as recorded by Edgar Rice Burroughs.

Only on one occasion, however, did the author allow his ape-man to feel

emotion so deep that it brought tears to his eyes. It happened when Tarzan

and Jane witnessed William Clayton die of jungle fever near the end of

The

Return of Tarzan.

“For a moment they remained kneeling there, the girl’s

lips moving in silent prayer, and as they rose and stood at either side

of the now peaceful form, tears came to the ape-man’s eyes, for through

the anguish that his own heart had suffered he had learned compassion for

the suffering of others.”

Never again in the ape-man’s saga would he shed a tear,

not even when he gazed down at the charred, dead body he believed to be

his wife in Tarzan the Untamed. “No tear dimmed the eye

of the ape-man,” the author declared, “but the God who made him

alone could know the thoughts that passed through that still half-savage

brain.” The violent exigencies of his primitive existence and a life-long

acceptance of fate left precious little room for self-pity in the heart

or eyes of Tarzan.

Tarzan of the Apes had super-human vision in the sense

that his eyesight and how he processed what he saw were developed to the

absolute maximum possible. In Tarzan Triumphant, when his

American companion failed to see the spoor Tarzan was following, the ape-man

responded, “Nothing that you can see perhaps, but then, though you may

not know it, you so-called civilized men are almost blind.” Later in

Sumatra, Tarzan explained to an American airman that vision and other senses

of civilized men had been “dulled by generations of soft living, of

having laws and police and soldiers to surround you with safeguards.”

In Tarzan’s case, however, his eyes worked in unison with

his other senses, not only to ensure his survival, but also to illuminate

a much more interesting life than civilization had to offer.

“In all that he saw or heard or smelled he read a story;

for to him this savage world was an open book, sometimes a thrilling, always

an interesting narrative of love, of hate, of life, of death.” (Tarzan

the Magnificent)

—the end—

![]()

.

. .

.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()