The Battle of the Pass of the Ancients

by Alan Hanson

There is something sublime about walking the ground of an

old battlefield. This is not so of the battles of our century, which have

been fought for the most part from a distance with rifles and artillery.

They are too impersonal. But in the battles of hundreds of years ago, when

antagonists carried the battle ax, the broadsword, or the claymore into

hand-to-hand combat, a soldier had to look into the eyes of the man he

killed or who killed him. Battles seem such wasteful things, but there

is inspiration in knowing that men from time to time held convictions so

strong that they were willing to come by the thousands and die that their

beliefs might live.

There is something sublime about walking the ground of an

old battlefield. This is not so of the battles of our century, which have

been fought for the most part from a distance with rifles and artillery.

They are too impersonal. But in the battles of hundreds of years ago, when

antagonists carried the battle ax, the broadsword, or the claymore into

hand-to-hand combat, a soldier had to look into the eyes of the man he

killed or who killed him. Battles seem such wasteful things, but there

is inspiration in knowing that men from time to time held convictions so

strong that they were willing to come by the thousands and die that their

beliefs might live.

On what field did Americans fight their greatest battle?

Historians might debate the significance of the struggles at such places

as Yorktown, Gettysburg, Chateau-Thierry, and Iwo Jima. Surely, though,

the greatest battle of all on the North American continent has yet to be

fought. It will be contested an April day in the year 2430 among the orange

groves at the western base of Cajon Pass in what we now call California.

(Note: The date given in the magazine version of The Red Hawk

was chosen over the date of 2434 given in the book version of The

Moon Maid.)

The only known account of this battle, which we will call

the Battle of the Pass of the Ancients, comes from the memoirs of

Julian 20th, the commander of the American forces on the field that day.

His account comes back to us, apparently, through an earlier pre-incarnation

of himself. Though the battle will be fought in the future, to make it

easier understand in the present day, the events surrounding the battle

will be recounted in the past tense.

A Racial Conflict

The Battle of the Pass of the Ancients

brought to an end 384 years of racial strife between the descendants of

the moon men, who invaded and conquered the earth in 2050, and the descendants

of the native Americans who were subjugated at that time. At the same time,

the battle brought to a close a feud between the families of Julian and

Or-tis that began in 2050 when Julian 5th and Orthis both died during the

decisive air battle of the moon invasion.

The moon men, or Kalkars, thoroughly subdued the

American people until Julian 9th led the first uprising against their authority

in 2122 in present-day Illinois. Over the next 300 years, the Americans

slowly forced the Kalkars westward and eastward across the continent. The

Kalkars’ ultimate fate on the eastern shore is unknown, but we do know

that in about the year 2300, Julian 15th drove the Kalkars across the Mojave

Desert, over the mountains and into the central valley of California. There,

with only narrow mountain passes to defend, the Kalkars held. At least

20 times in the next 100 years, the Americans went into the valley in force,

only to be driven back.

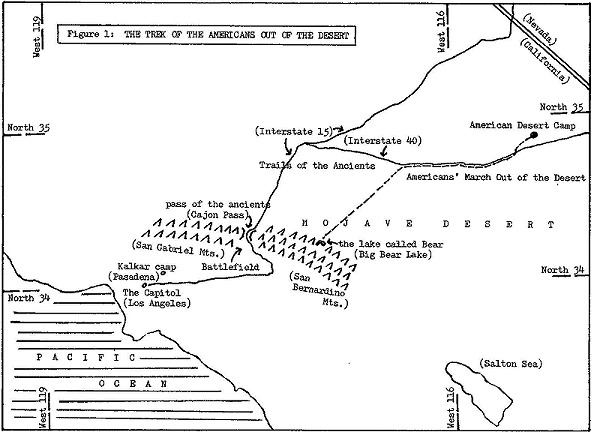

The Trek of the Americans

Out of the Desert

The Americans’ final assault on the

Kalkars awaited only a strong and imaginative leader. He was to be Julian

20th, who came to power in August 2429 at the age of 20. In January 2430,

Julian announced to his people that, following the spring rains, they would

move out of the desert to settle in the Kalkar valley. By April the thousand

clans that owed allegiance to the house of Julian had gathered at Julian’s

camp in the eastern Mojave Desert. Fully 50,000 people, half of them warriors,

started the trek, following “the trail the ancients used,” probably

remnants of Interstate 40 (see map 1). Julian, reasoning

that success depended on hiding their position and strength from the enemy

as long as possible, took his people off the trail after four days. To

hide their advance, he led them on a difficult march across a stretch of

desert and up into the mountains to “a like called Bear” by the

American’ slaves (Big Bear Lake in the San Bernardino Mountains). This

placed their camp about 25 miles to the east of the pass of the ancients

(Cajon Pass), where the Americans had attempted to enter the valley for

a hundred years and where the Kalkars had come to expect them.

Click for full size

The American Battle Plan

Being greatly outnumbered, Julian knew

he needed to draw the Kalkars into a major battle. A decisive victory would

leave the Kalkar military in confusion long enough for the Americans to

gain a secure base in the valley for further military operations.

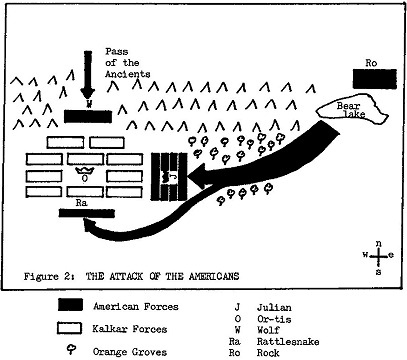

Julian’s strategy was to draw the enemy to a battlefield

of his choosing, while hiding the strength and location of his own force

from the Kalkars. He did this by keeping his main force at the Bear lake

camp and sending The Wolf with 1,000 warriors to the pass of the ancients

to stage three days of false advances. Julian’s hopes of luring a substantial

Kalkar force were realized. American scouts reported Kalkars filling every

trail from the south and west heading for the pass. Just as important,

no enemy scouts spotted the large American camp at Bear lake.

Once Julian had drawn the Kalkars into the field, he relied

on the maneuverability of his warriors and a surprise attack to win the

battle (see Map 2). On the evening of the third day of The

Wolf’s false attacks, Julian led 20,000 warriors slowly down the mountain

trails and into the orange groves in the foothills below Bear lake. Mounting

their war horses for the first time in two weeks, this force turned northwest

for a 25-mile ride to the Kalkar camp. About 10 miles from the enemy’s

position, The Rattlesnake was dispatched in a more westerly direction with

5,000 warriors to attack the Kalkars’ rear. Julian moved on with the main

force, intending to attack on the flank while placing himself between the

main body of Kalkars and their supplies and reinforcements.

Julian’s plan called for a surprise attack while the enemy

slept. The Rattlesnake’s orders were to attack as soon as his force was

in position, the sound of the assault being the signal for the forces of

Julian and The Wolf to move in. Advancing his force to within a mile of

the nearest Kalkar camp fires, Julian anxiously awaited the signal.

Click for full size

The Armies

Of the force of 25,000 warriors that

the Americans brought out of the desert, 4,000 did not engage in the fight.

They had been left under the command of The Rock to guard the Bear lake

camp. All of the 21,000 who did fight were mounted. The exact number of

the Kalkar force is unknown, although there is no doubt it greatly outnumbered

the Americans. Julian refers to it as “a great horde.” Most of the

Kalkars probably rode mounts to their camp, but many fought on their feet

as the American surprise attack prevented them from finding their horses.

Centuries of Kalkar rule resulted in a decline of scientific

knowledge to the point that the use of firearms was unknown, and they were

not used by either side during the battle. One thousand American warriors

were armed with bow and arrows. Other weapons carried by Americans included

lance double-edged swords and knives. The Kalkars used the same weapons,

only heavier. They also wore iron bonnets and vests of iron on their chests.

Choosing not to encumber themselves with the weight of the metal, the Americans

carried only a light shield on the left forearm for defense.

The Battlefield

When Julian led his attacking force

to the crest of a low ridge during his night advance, he got his first

glimpse of the field on which the battle would be fought. Before him stretched

a broad valley bathed in moonlight. Orange groves in the near foreground

would cover his final advance, and beyond to the northwest was a great

open area dotted with dying campfires. The wide-open ground suited the

agile Americans over the slow Kalkars, who, with their heavy weapons, would

be more effective in a more enclosed arena.

The Action

There was a crisis for the Americans

even before the battle started. For some reason never explained, The Rattlesnake

was delayed in reaching the rear of the Kalkars. If The Rattlesnake had

not been in position by the time the Kalkars began waking, Julian would

have been forced to attack from two sides only, giving the Kalkars an avenue

to retreat and reorganize. However, just at dawn the war drums of The Rattlesnake

sounded and Julian’s forces charged the camp.

Julian deployed his force along a two-mile front in the

groves, with the 1,000 archers in front and line after line of lancers

and swordsmen behind. As they charged, the bowmen fired at the confused

Kalkars. Those who escaped the arrows were trampled beneath the horses

of the lancers behind.

The tents of Or-tis were seen ahead, and there quickly

developed the battle center. The American advance was slowed as the warriors

crowded in upon one another, and some Kalkars were able to mount behind

the front lines. The battle soon became a matter of hand-to-hand combat,

as the two sides drove each other to-and-fro in a series of broken engagements.

The American strategy at this point turned to fighting

in a circular motion around the main body of Kalkars in an effort to close

off escape routes. By the end of the day, Julian reported he was back south

of Or-tis’ position, having fought all the way around it during the day’s

fighting.

Lulls in the conflict occurred as both sides fought to

the limit of endurance. The superb physical condition of the Americans

proved an advantage. Julian told of hundreds of Kalkars dropping dead in

the heat of the day, while only the very young and the very old among the

Americans succumbed to fatigue.

Fighting halted at nightfall when friend and foe became

indistinguishable. Julian, in keeping with his ultimate goal of exterminating

the Kalkars, was unwilling even then to give the Kalkars the opportunity

to retire from the field. The clans were formed in a solid ring around

the Kalkar position and ordered to hold their position during the night

and be ready for battle again at first light. It should be noted here the

extreme fatigue the Americans must have been feeling. They had just finished

an 18-hour battle and had not slept in 36 hours.

The Retreat of the Kalkars

If the Americans had hoped to get some

rest on the battlefield that night, they were denied it by a daring and

desperate Kalkar escape march. Toward dawn, Julian reported, the entire

body of Kalkars rode out in what he likened to “a great slow moving

river” toward the south down the broadening valley. In the middle of

the retreat must have been Or-tis, who never was seen during the battle.

The Americans cut the Kalkars down by the thousands from the sides and

front, but the sheer numbers of the enemy and the fatigue of the Americans

allowed thousands more Kalkars to leave the field and flee toward The Capitol.

Casualties

Julian did not provide casualty figures

for either side. However, several days after the battle, he told Bethelda

that “thousands” of Americans died. The Kalkar dead surely were

much higher. During the battle, Julian describes corpses of warriors and

horses so thick that living horses could barely climb over them. Sometimes

bodies were stacked so high that they formed barriers that had to be gone

around. During the retreat alone, thousands and thousands of Kalkars were

hacked down from the edges of the retreating mass. The following day, of

the Kalkar dead, Julian could only say that, “their losses must have

been tremendous I was sure.”

If Julian would not hazard a guess, let us do so. From

the account of the battle, let us place the American dead at 3,000 and

the Kalkar losses at four times that.

The Aftermath

The Kalkars had an opportunity to salvage

a peace with the Americans despite their crushing defeat when they captured

Julian himself during their retreat. However, it was a reflection of the

strength of the American leadership that their assault on The Capitol went

ahead without their top commander. Unable to bargain with Julian, Or-tis

ordered him executed, but the American eventually escaped to rejoin his

people.

As a captive in the Kalkar camp the day after the battle,

Julian judged from overhearing conversations that the defeat of the Kalkars

was complete, and they were fleeing toward the coast. In fact, he would

confide, “This first victory has been greater than I had dared hope.”

The Americans followed up the victory with an immediate assault on the

Capitol.

It was to take two more years of hard fighting to drive

the last of the Kalkars into the sea, but the fate of the two races had

been effectively decided in that epic battle on a fateful April day among

the orange blossoms below the pass of the ancients.

—the end—

![]()

.

. .

.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()