Race Issues in Edgar Rice Burroughs Fiction

Understanding Context in the Tarzan Stories

Part One: Black Slurs

by Alan Hanson

The Accusers

The Accusers

At Howard University on April 22, 1967,

Muhammad Ali gave a speech on the lack black pride in America. “We’ve

been brainwashed,” he said. “Everything good is supposed to be white

… Even Tarzan, the king of the jungle in black Africa, he’s white.”

On June 16, 1972, UPI news service reported that the chairman

of the Oregon Black Caucus protested Portland TV station KATU’s broadcasting

of a Tarzan series. “The ‘Tarzan’ movies are an insult to black people,”

Dr. Lee P. Brown said. “They perpetuate the myth of white superiority.

They are demeaning of the African nations as well as Americans of African

decent.”

Nine days later, a letter to the editor from Russ Manning

appeared in The Register, an Orange, California, newspaper: “When the

chairman of the Black Caucus, Dr. Lee P. Brown, noted the possible racial

slurs in the Tarzan movies, he showed his understanding of the situation

by attacking the movies, and not Tarzan himself. Dr. Brown has evidently

read the original novels and knows that Tarzan is above prejudice and intolerance,

that Tarzan mistrusts the entire human race, particularly ‘civilized’ man

and puts his truth in the individuals, black or animal, who have proved

themselves worthy of it.”

On the afternoon of April 9, 1989, the Historical Society

of Oak Park and River Forest met in the Chicago suburb to hear Edgar Rice

Burroughs collector Jerry Spannraft talk about the author, who had once

called Oak Park his home. During the question and answer period following

the presentation, an unidentified man in the audience stood up and began

reading a prepared text.

As it became clear that the statement was critical of

Burroughs’ treatment of blacks in his fiction, the ERB faithful in the

audience began to interrupt. “He was typical of his time!” “Have

you read the books?” “Make your point!” “Write a letter to

the paper.” A black man representing the NAACP then rose in the back

of the room to accuse the historical society of honoring a “racist”

author in Burroughs. As emotions heated up in the room, the historical

society’s president ended the meeting.

Now well into the 21st century, the criticism of Tarzan

continues to cast a shadow over his creator. The 87-year-old Harry Belafonte,

on receiving an honorary Oscar in Los Angeles on November 8, 2014, spoke

of the adverse effects the character of Tarzan has had on the minds of

young African Americans:

“In 1935, at the age of 8, sitting in a Harlem theater,

I watched in awe and wonder incredible feats of the white superhero, Tarzan

of the Apes. Tarzan was a sight to see. This porcelain Adonis, this white

liberator, who could speak no language, swinging from tree to tree, saving

Africa from the tragedy of destruction by a black indigenous population

of inept, ignorant, void-of-any-skills population, governed by ancient

superstitions with no heart for Christian charity.

“Through this film the virus of racial inferiority

— of never wanting to be identified with anything African — swept into

the psyche of its youthful observers. And for the years that followed,

Hollywood brought abundant opportunity for black children in their Harlem

theaters to cheer Tarzan and boo Africans … But these encounters set other

things in motion. It was an early stimulus to the beginning of my rebellion.

Rebellion against injustice and human distortion and hate.”

ERB’s Use of the “N-word”

In dismissing Harry Belafonte’s racial

indictment of Tarzan, Burroughs fans today could simply assume the same

fallback position that Russ Manning stated over 40 years ago — the ape-man

created by Edgar Rice Burroughs was a different, nobler, more open-minded

Tarzan than the one conceived by Hollywood.

As a Burroughs enthusiast, I certainly never considered

him a racist author. Along with the multitudes who have read his Tarzan

stories, I was drawn to the author’s exceptional story-telling ability.

The ape-man’s extraordinary capability to mold his environment to conform

to his inherent sense of right and wrong appealed to me. However, as the

examples above show, down through the years, Tarzan has from time to time

been branded a racist character. In the politically correct era in which

we live, such accusations will continue to surface occasionally, and even

if they are aimed at the film portrayals of Tarzan, they must inevitably

reflect upon the reputation of the ape-man’s creator, Edgar Rice Burroughs.

Had I been in the audience at Oak Park back in 1989, I

might well have risen to defend Burroughs as others did. In reflection,

though, it seems to me that ERB fans need to be less emotional and more

thoughtful about the strategies they use to address accusations that Burroughs

was a racist author. For example, to say he was “typical of his time,”

is no defense at all. It’s essentially admitting that he was a racist,

just like many other white people during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

There were some whites, however, who had the courage to stand up and speak

out for black civil rights during that era, and if some ERB fans think

he should be counted in that group, then they have to provide justification

to support that contention. Is there such evidence in Burroughs’ fiction

to suggest he was sympathetic to the rights of black people? Perhaps, but

it would require first overcoming some difficult obstacles in the Tarzan

stories.

That leads to another problematic line of defense a Burroughs

enthusiast voiced at the Oak Park meeting in 1989 … “Have you read the

books?” It’s certainly fair to question the critical statements of

someone who has not read ERB’s fiction. But might suggesting that such

critics read the Tarzan stories backfire? Is it possible that they might

find there more evidence they can use to support their racist charges?

For instance, the author has been accused of implying white superiority

in Africa through his common usage of the term bwana in his Tarzan stories.

(See “Tarzan and the Bwana Indictment” at https://www.ERBzine.com/mag73/7370.html)

The present purpose here, though, is to consider ERB’s

use in his fiction of other, more sensitive and emotional terms, namely

black racial slurs. In his 1972 letter noted above, Russ Manning inferred

that racial slurs do not appear in Burroughs’ Tarzan stories. In fact,

by my count, Burroughs used the term nigger, the most sensitive of such

slurs, 44 times in 10 of his published Tarzan stories, starting with The

Eternal Lover in 1914 and continuing through Tarzan the Magnificent

in 1937.

Some Burroughs fans find the discussion of such a topic

concerning their favorite author distasteful. However, the accusation that

ERB is a racist author is not going to just go away. It will resurface

from time to time, and if Burroughs fans want the ability to mount a reasoned

defense, they must know what appears in his writing that critics might

use against him.

These days the mere appearance of black slurs in Burroughs’

works would be enough for some activists to condemn him, but knowledge

of the context in which he used those terms can be the basis for a strong

counter argument. We know, for instance, that in some communities, zealots

have tried to have books, such as Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn

and Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, banned from local

libraries and schools on the sole basis that the term nigger appears in

the text. Anyone who has read those stories, however, knows that in both

novels the term is used in a negative context to further the author’s theme

that discrimination against black people has always been irrational and

harmful.

It’s not fair, then, to Twain and Harper, or to any author,

including Burroughs, to criticize the use of the term without first examining

how and for what purpose they employed what was a commonly used slur in

the first half of the last century. Racial segregation was then legal and

widely practiced in many sectors of American society, including in schools

and in the military.

Examining the context in which Edgar Rice Burroughs used

black racial slurs in his fiction will help clarify how he should be judged,

as an author, on the subject of racial tolerance.

The Evidence: The “N-word”

in the Tarzan Stories

When I originally read all of Edgar

Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan stories in Ballantine paperback editions back in

1963 and 1964, the author’s use of the word nigger escaped me. For the

most part, that was because it had been edited out or replaced by innocuous

alternate terms in all but one of the Ballantine editions. (For the record,

the nine Ace Books Tarzan titles published in 1963 were faithful in all

respects to Burroughs’ original text.)

It wasn’t until over three decades later, when my aging

eyes prompted me to switch to the larger type in Grosset and Dunlap hardback

reprints, that I realized Burroughs had used the racial slur in some of

his Tarzan stories. Burroughs also used the term in a handful of non-Tarzan

titles (The Mucker, Marcia of the Doorstep,

The

Man-eater, Pirate Blood), but this survey will focus

solely on its use in Burroughs’ far more prominent Tarzan stories.

Burroughs first used the slur in The Eternal Lover,

written in 1913. In the story, when an American woman, Virginia Custer,

is apparently abducted from Lord Greystoke’s African estate, Tarzan and

several other men set out to track and rescue her. When they later come

upon Nu, a resurrected cave man from a bygone era, William Curtiss, a suitor

of the missing girl, confronted the suspected kidnapper. “Where is Victoria

Custer? And when you speak to me remember that I’m Mr. Curtiss — you damned

white nigger.”

Burroughs portrayed Curtiss as an arrogant and intolerant

young man. Neither Tarzan nor Barney Custer, Victoria’s brother, used the

slur in the story. In fact, Barney patiently tried to explain the reason

for Curtiss’ anger to Nu. “‘I see,” said Nu. “And what is a ‘nigger’

and a ‘mister’?” Burroughs noted only that, “Again Barney did his

best to explain.”

The following year the author used the slur just once

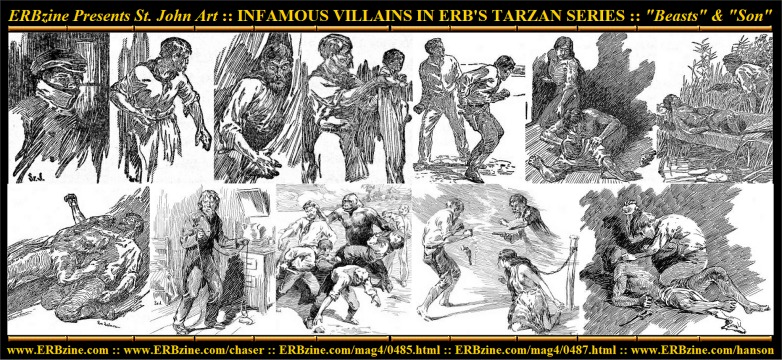

in his third Tarzan novel, The Beasts of Tarzan. The term

surfaced in dialogue by Gust, an unsavory Swede, who engaged in mutinous

intrigue with other cutthroats on a pirate schooner. Gust’s use of the

degrading slur infuriated a shipmate:

“Ah!” exclaimed Gust, “there is where you are

wrong. There is where you are lucky that you have an educated man like

me to tell you what to do. You are a poor nigger, Momulla, and so you know

nothing of wireless.”

The Maori leaped to his feet and laid his hand upon the

hilt of his knife. “I am no nigger,” he shouted.

Burroughs used the slur again in his next Tarzan story,

1915’s The Son of Tarzan. This time two evil Swedes got into

an argument after one attempted to molest the captive Meriem.

“You’re getting damned virtuous all of a sudden,”

growled Malbihn. “Perhaps you think I have forgotten about the inn keeper’s

daughter, and little Celella, and that nigger at—”

“Shut Up!” snapped Jenssen.

Between 1916 and 1921, Burroughs wrote four more Tarzan

novels, but did not use the slur in any of them.

Then, in 1922’s Tarzan and the Golden Lion,

the term appeared eight times. All were voiced in dialogue by disreputable

members of a band of conspirators, who came to Tarzan’s Africa intent on

stealing a fortune in gold from the treasure vaults of Opar. Four of the

conspirators used the slur in reference to African natives, either porters

employed by the conspirators or tribes that threatened the safari.

Adolph Bluber: “It takes more as a bunch of niggers

to bluff Adolph Bluber.”

Flora Hawkes: “You just tell Owaza that you’re thinking

of

going after Tarzan of the Apes and his Waziri to take the gold away from

them, and see how long it’d be before we wouldn’t have a single nigger

with us.”

John Peebles: “What in ’ell are we goin’ to do wanderin’

around in this ’ere jungle without no niggers to hunt for us, or cook for

us, or carry things for us, or find our way for us … ”

Dick Throck: “I guess there ain’t nothin’ else to do,

but blime if I likes to run away, says I, leastwise not for no dirty niggers.”

It would be five more years before Burroughs would again

use the notorious slur in his fiction. In 1927’s Tarzan, Lord of

the Jungle, American big game hunter Wilbur Stimbol revealed a

deep-seated racial streak by repeatedly referring to his safari’s porters

and askari with the demeaning term. He called a porter who dropped his

load, a “damned clumsy nigger,” and told another, “I’m not paying

you damned niggers for advice. If I say hunt, we hunt, and don’t you forget

it.” Later he told his hunting partner James Blake, “I don’t chum

with niggers.”

After deciding to go his separate ways following an argument

over Stimbol’s treatment of the native carriers, Blake suggested they offer

the men extra pay to split the safari. “My men will live up to their

original agreement,” Stimbol declared, “or there’ll be some mighty

sick niggers in these parts.” Later, when his “boy” didn’t come

to Stimbol’s tent when called, the American grumbled, “The lazy niggers.

They’ll step a little livelier when I get out there.” He soon learned

that all his men had left, leaving him alone in the jungle.

The next time the offensive slur appeared in a Burroughs

Tarzan novel, a much different and unexpected character gave voice to it.

Having grown up in Alabama, Robert Jones would have heard countless racial

slurs directed at him and other Southern blacks. Apparently they became

part of his own vocabulary, as he used the most common one twice while

serving as the cook at the 0-220 airship’s expedition to Pellucidar in

Tarzan

at the Earth’s Core.

After awaking from a nap on the ship’s landing, he, “yawned,

stretched, turned over in his narrow berth aboard the 0-220, opened his

eyes and sat up with an exclamation of surprise. He jumped to the floor

and stuck his head out of an open port. ‘Lawd, niggah!’ he exclaimed;

‘you all suah done overslep yo’sef.” And later, as he watched 10

Waziri warriors leave the ship to search for Tarzan, Jones swelled with

pride. “Dem niggahs is sho nuf hot babies,” he murmured.

Burroughs’ stereotypical portrayal of Jones and other

black American characters in his fiction is another racial theme that needs

to be considered. Keeping to the present topic for now, though, it’s clear

that Robert Jones’ use of the slur in question was Burroughs attempting

to use a stylistic idiom of self-expression used by many black Americans

of that era in reference to each other.

In Burroughs’ next Tarzan novel, Tarzan the Invincible,

the racial slur is used twice during a confrontation beneath the haunting

walls of Opar. Russian villain Peter Zveri and his fellow conspirators

had brought 10 native followers with them to pillage Oparian gold to finance

their plot to foment a European war. When Zveri ordered the reluctant askari

to enter Opar, guns were raised on both sides. “Lay off, Peter,”

said one of the other conspirators. “You will have the whole bunch on

us in a minute and we shall all be killed. Every nigger in the outfit is

in sympathy with these men.”

Entering the edifice without the askari, the conspirators’

nerves were rattled by the echo of a warning scream. “Shut up,”

Zveri told one of them. “Stop thinking about it, or you’ll go yellow

like those damn niggers.”

In Tarzan Triumphant, the slur is used only

once, and that, for a change, by a likeable character. Danny “Gunner” Patrick,

a small time Chicago racketeer hiding out in Africa, intended to compliment

his hometown African Americans when he told his traveling partner, “most

of ’em is regular, at that. I knew some nigger cops in Chi that never looked

to frame a guy.” (The lovable, uneducated Chicago hood also used a

variety of other slurs to refer to blacks. Those will be detailed in Part

2.)

When Burroughs wrote Tarzan and the Lion Man

in 1933, he used nigger in narration for the first and only time in his

fiction. Referring to Tom Orman, the director of a Hollywood movie company

filming on location in Africa, the author noted, “It seemed to him that

everything had gone wrong, that everything had conspired against him. And

now these damn niggers, as he thought of them, were lying down on the job.”

It should be noted, though, that Burroughs made it clear parenthetically

that he was, in effect, quoting a character’s thoughts.

Portraying Orman as an arrogant and angry alcoholic, Burroughs

had him repeatedly demean his black porters. On learning one morning that

some had deserted during the night, Orman declared, “We still got more

niggers than we need anyway.” And when other members of the company

counseled him to put an end to the expedition, the director growled, “Well,

turn back if you want to, and take the niggers with you. I’m going on with

the trucks and the company.”

Another character, Jerrold Baine, an actor in the

company, earlier had advised Orman, “to treat those niggers rough.”

It should be noted that in 1933 Burroughs was able to sell the first serialization

of Tarzan and the Lion Man to Liberty magazine, and so reach

a much wider audience than available through the pulp magazines that published

his other Tarzan stories.

In the two parts of Tarzan the Magnificent,

written by Burroughs in 1936-37, he used the slur 10 times, by far the

most among all of his Tarzan stories. (For some unknown reason, although

Ballantine Books excised every use of the racial slur from all the other

Tarzan books it published, none of its appearances were removed from Ballantine’s

first 1964 paperback edition of Magnificent, nor from any

of its subsequent printings.)

All 10 uses of the slur appeared in dialogue voiced by

Spike and Troll, a pair of felonious African hunters in the story:

Spike: “I never knew it to fail that you didn’t get

into trouble with any bunch of heathen if you started mixin’ up with their

women folk — especially niggers. But a guy’s got it comin’ to him that

plays around with a nigger wench.”

Spike: “You (Tarzan) mean to say you’re goin’ to give

the big rock back to the niggers and we don’t get no split?”

Spike: “The bloke’s balmy. The nerve of him, givin’

the Gonfal back to them niggers.”

Troll: “An he (Tarzan) gives the emerald to that damn

nigger wench (Gonfala). Wot’ll she do with it? The American’ll (Stanley

Wood) get it. She thinks he’s soft on her, thinks he’s goin’ to marry her;

but whoever heard of an American marryin’ a nigger.”

Spike: “You (Troll) may need another gun in some of

the country we got to go through. You’d never get through alone with just

six niggers.”

Spike: “In the first place we got to see that she (Gonfala)

doesn’t get to touch it (the Gonfal). One of us has got to carry it — she

might get the nigger to let her touch it some time when we weren’t around.”

Spike: “Come on, you niggers! Come on, Gonfala! We’re

trekkin’—the sun’s been up an hour.”

Troll: “You (Gonfala) don’t want to go to that there

valley and spend the rest of your life with Spike an’ a bunch o’ niggers,

do you?”

The Context

Now that all of the uses of the term

nigger in Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan stories have been revealed, it’s

time to take a close look at the context in which Burroughs used that slur.

To recap, in Burroughs’ 28 published Tarzan stories, the

term nigger appears 47 times. Two-thirds of those are crowded into four

stories — Tarzan and the Golden Lion; Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle;

Tarzan and the Lion Man; and Tarzan the Magnificent.

All but one of the 47 uses appear in dialogue voiced by

various characters in the stories. As noted earlier, the only time Burroughs

used the offensive term in narration was in Tarzan and the Lion Man.

It that instance, he made it clear that he was, in effect, quoting a character’s

thoughts. In effect, then, Burroughs only used black slurs as a characterization

tool in his Tarzan stories. The question then becomes: What type of characters

voiced the term nigger in Burroughs’ fiction?

It must be made clear up front that Tarzan, himself, never

voiced a black slur of any kind in Burroughs’s fiction. Of the 46 uses

of the term nigger in dialogue, 39 were spoken by white men, 3 by a white

woman, and 4 by black men. Most of ERB’s white male characters who uttered

the term were unmistakably evil villains. Two examples are the American

hunter Wilbur Stimbol in Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle and the

African hunters Spike and Troll in Tarzan the Magnificent.

Burroughs only created one endearing white male character who constantly

used black slurs. That was Danny “Gunner” Patrick in Tarzan Triumphant.

The only Burroughs white female character to use the term was Flora Hawkes

in Tarzan and the Golden Lion.

Burroughs presented Stimbol as an egotistical counterpart

to the kindly James Blake in Lord of the Jungle. A thoroughly

arrogant bigot, Stimbol’s cruelty toward the safaris’ native porters is

established early in the story:

“‘You damned clumsy nigger!’ he cried, "and

before Blake could interfere or the porter protect himself the angry white

man stepped quickly over the fallen load and struck the black a terrific

blow in the face that felled him, and as he lay there, Stimbol kicked him

in the side.”

James Blake at first tried to temper Stimbol’s cruelty.

The young American attempted to convince his older partner that the porters

would have responded much better to kindness than to intimidation.

“These black men are human beings. In some respects

they are extremely sensitive human beings, and in many ways they are like

children. You strike them, you curse them, you insult them and they will

fear you and hate you. You have done all these things to them and they

do fear you and hate you. You have sowed and now you are reaping.”

The malevolent Stimbol ignored Blake’s advice, and after

the young American insisted that the safari be divided and each go their

separate ways, Burroughs made Stimbol pay for his bigotry. After his native

carriers deserted him in the night, a frightened Stimbol experienced a

series of setbacks that left him near death. At the end of the story, Tarzan

ordered the racist American out of Africa.

Burroughs gave much the same treatment to the racist white

African hunters Spike and Troll, who collectively used the term nigger

10 times in Tarzan the Magnificent. After Tarzan helped the

two men escape captivity among the Kaji tribe, they repaid the ape-man

by stealing from him and kidnapping a woman he had taken into his care.

Eventually, Tarzan tracked down the inveterate villains and expelled them

from Africa.

As the only woman who used racial slurs in Burroughs’

Tarzan series, Flora Hawkes in Tarzan and the Golden Lion

warrants a closer look. As one of the leaders of a band of conspirators

intent on raiding the gold vaults of Opar, she was initially painted as

a villain by Burroughs. In that role, she three times crudely referred

to her safaris’ native retainers as “niggers.” However, Burroughs

subjected her to the horrible punishment of being kidnapped and raped by

one of her fellow conspirators, and at the story’s end she was redeemed

only after dropping to her knees and begging the forgiveness of Tarzan

and Jane.

Also in Tarzan and the Golden Lion, Burroughs

employed irony by having Flora’s fellow conspirator Adolph Bluber use racial

slurs in referring to African natives. The German resented his collaborators

disparaging his Jewish heritage, but he failed to see the absurdity of

his own use of black slurs. On one hand, he objected to bigotry directed

toward him. “Ven you get mad at me you call me a dirty Jew,” he

told his white partners, “but Mein Gott! You Christians are worser.”

But when he maligns natives using slurs, he forgets that Tarzan’s Waziri

warriors saved his life by routing the native warriors who attack the conspirators.

Burroughs, then, clearly characterized Bluber’s use of racial slurs as

insensitive behavior by a man who, as a target of ethnic slurs himself,

should have known better.

Establishing that Edgar Rice Burroughs employed the racial

slur nigger in only 10 of his 28 Tarzan stories, and then almost exclusively

in dialogue voiced by villainous and/or uneducated characters is an effective

argument in defending the author against charges of racism. However, those

charges can extend well beyond the use of slurs, and so Burroughs defenders

must be prepared with a much more comprehensive argument on his behalf.

— to be continued in Part Two —

![]()

.

. .

.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()