Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute and Weekly Webzine Site

Since 1996 ~ Over 15,000 Webpages in Archive

Master of Imaginative Fantasy Adventure

Creator of Tarzan and "Grandfather of American Science Fiction"

Volume 7876In the 1960s Editorial Burguera, of Spain and Brazil, with the authorization of Western Publishing, the parent Company of Whitman Books, published a series of juvenile adventure novels, primarily featuring characters from TV series. These books are similar in concept and format to the USA full size Whitman books of the 1950s and 1960s. (Most fans are aware that those USA books include 5 Tarzan books: revised editions of Apes, Return, City of Gold, and Forbidden City, and a novelization of Tarzan and the Lost Safari.) A total of 68 books were published by Bruguera, including volumes about Bonanza, Broken Arrow, Bronco, Buffalo Bill, Daniel Boone, Davy Crockett, Fury, Lassie, Rin Rin Rin (16 volumes!), Robin Hood, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, Captain Thunder (Capitán Trueno, an extremely popular Spanish comics character) and, last but not least, Tarzan.

Bruguera’s Spanish Tarzan "Whitmans"

by Ward Orndoff

Four Tarzan books were published:

Title Translated Title Publication Date

El Último Ciervo (The Last Deer) April 1964

El Zoo del Circo (The Circus Zoo) August 1964

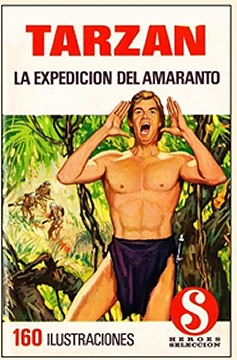

La Expedición del Amaranto (The Amaranth Expedition) September 1964

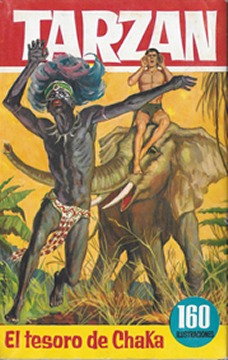

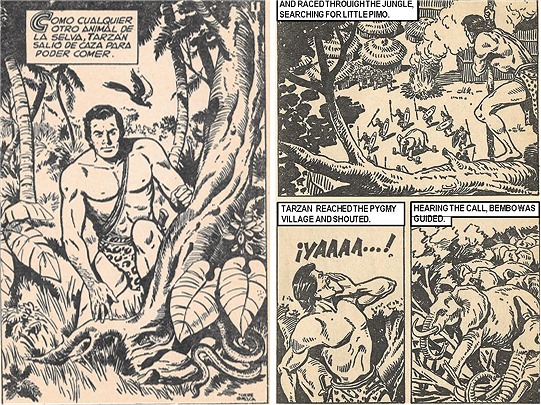

El Tesoro de Chaka (The Treasure of Shaka) December 1964The Tarzan books were reprinted in 1966 with the same covers, and again in 1969, with the same dust jacket art but revised cover layout, and different book front cover art (see below). They measure 7 ¾ x 5 ¼ inches (13.3 x 19.6 cm), essentially the same size as the USA Whitman Books, and contain 239 pages each. The prose stories range in length from 44,000 to 60,000 words. In addition, 60 pages contain full-page illustrations, in black and white comic book style, with 2 or 3 panels of art per page, and word and narrative balloons (see examples below). These 60 pages tell the same story as the prose text (more or less; some details are simplified, and others are simply different, as if the story used for one version was revised during editing of the other version.

1964, 1966 book front covers and dust jackets

1964, 1966 book and dust jacket 1969 dust jacket 1969 book front cover

Terregrosa AmbrósThe novels were also issued by Editorial Burguera in Portuguese in 1965-1966, in a very slightly smaller size (7 ½ x 5 1/8 inches), with the same cover art as the 1964 Spanish editions. The one Portuguese language volume I have (O Último Cervo) contains 232 pages of story and illustrations instead of 239. This may be due in part to language differences – the Portuguese books were translated from the Spanish – or it may be due to subtle differences in font style or size. The book contains 60 pages of illustrations, like the Spanish edition, but they are not arranged on every fourth page in some places, due to the slightly smaller total number of pages.

No authors or artists are listed in the Tarzan books, though you can see Terregrosa’s name in the splash page illustration on the left above from The Last Deer (the same is true for The Circus Zoo). I have found the artist and writer names for the 60 pages of illustrations for three and a half of them:

Artist Writer

El Último Ciervo Vicente Terregrosa Manrique Eduardo Romero

El Zoo del Circo Vicente Terregrosa Manrique José María Carbonell Barberá

La Expedición del Amaranto Miguel Ambrosio Zaragoza (Ambrós) ? also Ambrós ?

El Tesoro de Chaka Vicente Terregrosa Manrique José Garcia EsplugaThe 60 pages of illustrations in The Amaranth Expedition by Ambrós have been reprinted twice as a stand-alone story by fans of the artist, once as a single chapbook and once in 3 volumes in a considerably larger size (9 5/8 x 6 ¾ inches) . I have not found any information regarding the writers of the prose stories themselves (the writers listed above wrote the dialog / narrative text for the illustrated stories). I say authors plural because differences in terms and phrasing from book to book, as well as differences in supporting characters, lead me to believe that the books were not all written by the same author. But bear in mind that this is just my opinion, not established fact.

The Tarzan books are based more on the then-current Tarzan films than on the novels of Edgar Rice Burroughs. Tarzan is a young adult in all of them, but he is already king of the apes (king of all the apes of all the tribes in the region, according to The Last Deer). In The Amaranth Expedition, it is mentioned that some twenty years have passed since the aviation accident (!) that left him an orphan at a very young age. There is no mention of Jane in any of the stories. Two of the four books feature Cheeta as Tarzan’s companion, not Nkima. A third, The Circus Zoo, features Kala, Tarzan’s adoptive mother, instead of Cheeta, but she acts, and is illustrated, exactly like Cheeta. At one point, Tarzan digs a small tunnel for her to use to get into a tent, and the people who find it later state that the tunnel is much too small to allow the passage of a man. Did the story get written with Cheeta and then see the character renamed as Kala? Pure speculation on my part. The Last Deer has Manu the monkey instead of Cheeta. It also features a young bull ape named Kerchak, but he is an aspirant to the crown, and Tarzan is already the king of all the tribes of great apes in that particular book. I changed his name to Kartak. In The Amaranth Expedition the elephant herd leader, and Tarzan’s particular friend, is named Bembo instead of Tantor, and there is a little elephant named Pimo, which Cheeta rides.

As for plots, all four novels employ the popular “safari in trouble” theme. In The Last Deer, a hunter and his teenage son go hunting for examples of a rare species of large deer that only exists in Tarzan’s domain, with the goal of breeding and selling them. He and Tarzan get off on the wrong foot. A tribe of natives building traps to catch large animals complicates matters. In The Circus Zoo, a circus owner and part of his company go on an expedition to catch young animals to replace trained animals lost in a fire. Tarzan objects, but does not want to harm them, so he plays tricks on them to discourage them, to no avail (but considerable amusement). After numerous hardships, they are captured by hostile natives, and it’s Tarzan and a tribe of friendly natives to the rescue. In The Amaranth Expedition, a botanist, his daughter, and a zoologist organize an expedition to find the rumored South African variety of the Amaranth flower and study carnivorous animals. Accompanying them are two men who have their own agenda. Separately, a tribe of pygmies captures Pima, the small elephant that Cheeta rides. Tarzan and the elephants rescue Pima and demolish the pygmy village. The pygmies seek revenge, and it spills over on the expedition. The Treasure of Shaka features (William) Cecil Clayton, Member of Parliament, who decides to make a return trip to Africa after being prevented by Winston Churchill from engaging in a duel. Cecil feels guilty about accepting the title and inheritance from his cousin Tarzan, after Tarzan saved his life, and wants to give him another chance to accept his heritage. Clayton is accompanied by a Dutchman he met at the almost-duel, and the man’s niece. The Dutchman hopes to find the remains of his relatives, lost in the Boer War, or news of them. So they set off for Zululand, with a not-so-helpful guide. Tarzan meets up with them along the way. Problems ensue. Again, Jane is not mentioned in any of the books.

I personally found the four stories enjoyable, and rather similar in tone and reading level to the USA Tarzan and the Lost Safari Whitman adaptation written by Castle. They are indeed juveniles, aimed primarily at the 10 – 15 year old reader, as opposed to their smaller Big Little Books, which are aimed more at 8 to 10 year olds, but they do not talk down to the reader. If the reader accepts the movie Tarzan of the 1950s and early 1960s, he or she should not find anything objectionable here. In general, I tried to translate them, not edit them, but I did take the liberty of changing “deadly” hyenas to panthers/leopards in two cases in The Amaranth Expedition. In one case, a hyena attacks 2 men in a deserted camp. In the other, Tarzan battles a hyena that attacks his party of four. (Whoever wrote this story seemed to think hyenas were the apex predator of Africa. ;) ) In the illustrations, Tarzan battles a black panther, not a hyena, so one could say I simply resolved a discrepancy. As for the attack on the 2 men at the deserted camp, the illustrated version skips the attack, so no new discrepancy between prose and illustrations was created.

Written in the 60s, these stories contain an occasion passage or description that would not be regarded as politically correct today. In my humble opinion, they are not particularly racist, but they are a product of the times. I changed “primitive minds” to “uneducated minds” in several places in referring to natives but otherwise left things as written. In general, they feature good natives and bad natives, just as they include good whites and bad whites. Two of the natives in particular display exemplary character, courage and loyalty. In fact, at one point a young woman in one of the safaris, commenting on the heroic, selfless actions of a native assistant in creating a diversion to save the others, at great risk to himself, and without being asked, notes that some of those who embrace white superiority might want to reexamine their point of view based on the man’s heroics.

Both Western and Bruguera have since closed their doors. Bruguera’s rights were passed on to Penguin/Random House, and later Ediciones B, according to what I have managed to find online. (Don’t take my word for this; I am neither a copyright expert nor an accomplished researcher.) Some volumes of the “Heroes Collection” were reprinted in 2006, but no Tarzan titles were reprinted then, perhaps because the rights to those novels reside with ERB, Inc. The 1960s Tarzan editions state copyright 1964 and 1969 by ERB, Inc., depending on the edition, and 1969 is recent enough that, in my humble opinion, the copyright would still be in force, regardless of whoever else has any rights.

With that in mind, I contacted Cathy Wilbanks at ERB, Inc., and asked her if they would be interested in the translations (free, of course; I was not hired to translate the books, I just did it for fun). Cathy was happy to accept them, though she did note that their plans did not currently include any juveniles. (Hopefully the Tarzan Twins stories are still on their “to be reprinted” list; I did not think to ask.)

Meanwhile, for those who understand Spanish, the books are readily available on abebooks or todocolección for reasonable prices (except for the cost of shipping from Spain).