|

|

Carson Napier’s Anotar

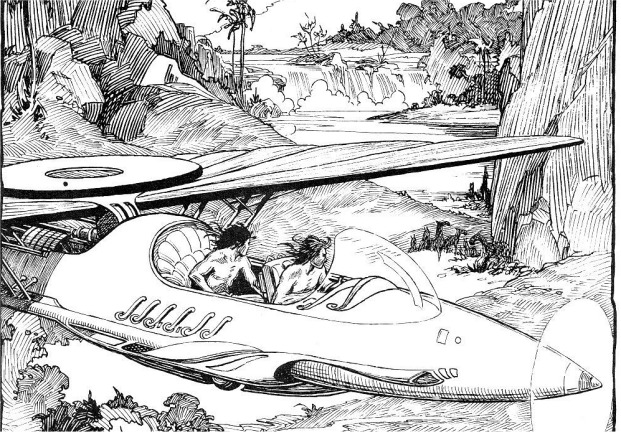

Anotar art by Roy G. Krenkel.

by Fredrik Ekman

Originally published in ERB-APA #101.Edgar Rice Burroughs had a well documented interest in aircraft and flying. He had a pilot license, and for a few days in 1934 he owned a Security Airster S-1-A, before his son Hulbert crashed it during landing.

Burroughs’ brief experience as a pilot was without a doubt formative for the final parts of his Venus (Amtor) series. In Lost on Venus (1932), our hero Carson Napier constructed the first aircraft to be flown on Venus. It is not described in any detail in that book, and only used as a plot device very briefly towards the end. In the next book, however, Carson of Venus (1937), the entire plot is built around the craft, named anotar in Amtorian. “It was a good name, too; for notar means ship, and an is the Amtorian word for bird—birdship.” (CV/1)

In all there are three different versions of the anotar. The first (which I will refer to as the Mk I) is the original one constructed in Havatoo. This is the one on which the main portion of this article will be based. Only a single machine of this kind was built.

The second one (Mk II) was built by Ero Shan after Carson had left Havatoo. We know that it must differ from Mk I because “some of the essential features [...] were not on [Carson’s] drawings” (EV/33) so Ero Shan and his fellows were forced to complete it by trial and error. More than one Mk II may have been manufactured. Mk II does not appear in the novels other than being briefly mentioned.

The final version (Mk III) is the one that Carson and Ero Shan fly in The Wizard of Venus. Carson “incorporated some new ideas in its design” (WV/2) but exactly how it differs from the previous ones is not known. It may actually be inferior in some respects since it was built in Sanara, without access to the advanced science of Havatoo. Two aircraft of this kind were produced simultaneously, more yet may have been forthcoming. (The double production was probably a plot device. I am guessing that the novelette cycle started with The Wizard of Venus was intended to be concluded with a magnificent rescue effected by Duare in the extra Mk III, but this will forever remain speculation.)

Sources of Inspiration

Carson says about the anotar: “In design the ship was more or less of a composite of those with which I was familiar or had myself flown on Earth.” (CV/4) For this reason it is valuable to try to figure out what aircraft Carson was likely to have encountered.Carson probably went to Venus in 1931 (see my Venus chronology in ERBzine #1631) and he finished constructing the Mk I towards the end of the following year, so any later earthly aircraft than that could not reasonably inspire the anotar, even considering Carson’s fantastic psychic powers. A complicating factor is that Burroughs must have continued to be inspired by new aircraft as he wrote the series. This, as we shall see, leads to some interesting contradictions.

The only type of aircraft that we can say with absolute certainty was flown by Carson is “his Sikorsky amphibian” (PV/1). This was almost certainly the S-38 model, not only because of its popularity but also because its size would be perfect for his rocket construction project. In theory, however, it could have been S-36, S-37 or S-39.

Apart from the S-38 there are also several other models which for various reasons we can assume that Carson flew.

By far the most popular stunt plane in the 1920s was the Curtiss JN-4 (nicknamed “Jenny”). Thousands of surplus Jennies had been sold after World War I and they were used by barnstormers and in many movies. It is very probable that Carson came across the model when he “became a stunt man in pictures” (PV/1) around 1926, and also other surplus war planes such as the Thomas-Morse MB-4.

During the late 1920s the Jenny would come to be replaced as the most popular light aircraft by the DeHavilland Tiger Moth, which made its first flight in 1925. If Carson showed the slightest interest in flying during his years in Europe then he must have almost certainly flown the Moth.

When writing, it is of course natural that Burroughs was most strongly influenced by his own aircraft. Reasoning backwards, it would be convenient to assume that Carson shared that source for inspiration. Unfortunately, Carson cannot possibly have flown a Security Airster, since it did not make its maiden flight until 1933. The Airster was developed from an early model of the Kinner Sportster but that, too, came too late. However, the Sportster in turn was developed from the Bolte LW-2. The LW-2 first flew in 1928 and, like the Airster, was a low-winged monoplane accommodating two. The main design difference between the two was that the LW-2 seated two persons tandem, rather than side by side. It is possible that Carson may have purchased or rented an LW-2 upon his return from Europe in 1929.

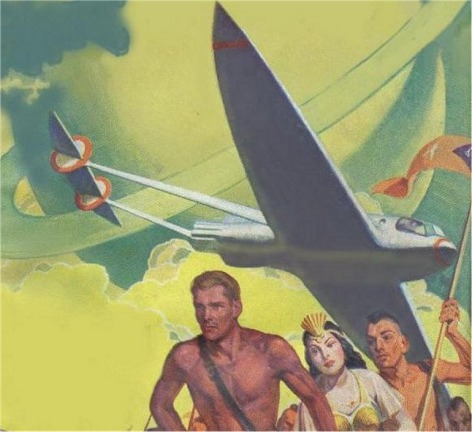

This very fanciful design looks more like a jet than a propeller plane, with its twin booms and rear exhaust. 1938 Argosy cover art by Belarski.Performance

Burroughs gives no specifics regarding the anotar’s performance data, but some figures can be inferred.Carson and Duare took almost exactly one night and one day to travel from the far side of Vepaja to the coast of Anlap (CV/4). Vepaja is “some four thousand miles long” (CV/19) and there are “at least fifteen hundred miles of ocean” (Ibid.) between the two continents, so the total distance flown was 5,500 miles (8,851 km). “The Amtorian day consists of 26 hours, 56 minutes, 4 seconds of earth time” (PV/10). This gives an average cruising speed of 204 mph (329 km/h).

The maximum speed can also be calculated, although with larger margin for error. Carson’s escape from Amlot took a total of four hours. Half that time was spent in his boat and then perhaps another three quarters of an hour attending to other business. The remaining 75 minutes (or less?) were spent flying from the island outside Amlot to Sanara. Ten miles to Amlot plus another 500 miles to Sanara gives a total of 510 miles (821 km). Carson was “running the engine at maximum all the way” giving a max speed of 408 mph (657 km/h). (CV/13)

It is also possible to calculate the speed for Mk III. When exploring 6,000 miles (9,656 km) of Anlap, Carson estimates that “we should make the round trip in something like twenty-five hours flying at full speed” (WV/2). It is not clear whether he means earth hours or Amtorian te. Assuming the former will give a max speed of 480 mph (772 km/h). He further states that “as I wished to map the country roughly, we would have to fly much slower on the way out. However, I felt that three days would give us ample time.” (Ibid.) The exact implications of this depends on how many hours are spent airborne. Assuming that they are half the time in the air, half on the ground would give a cruising speed of 215 mph (346 km/h). Thus, Mk III actually seems faster than Mk I. (In reality I suspect that Burroughs intended all models to have a max speed of 500 mph (805 km/h) but there is no hard evidence for such a hypothesis.)

Landing and take-off speeds are not known. We are only told: “The anotar is quite maneuverable and can fly at very low speeds” (EV/21).

The service ceiling of the anotar is another unknown. Due to the dense Amtorian clouds, Carson rarely flies very high. Only once has he flown above the inner cloud layer which envelops everything above 5,000 ft (1,524 m). “We climbed rapidly, and at fifteen thousand feet we emerged into clear air” (WV/3). This only tells us that the anotar can in all probability go high above 15,000 ft (4,572 m), but we could infer that much anyway based on the max speed.As regards the aeroplane’s loading capacity, Carson claims that “she would easily lift a load of fifteen hundred pounds” (CV/14), or approximately 680 kg. Included in that is the craft’s maximum limit of four passengers.

The ratio between empty weight and maximum take-off weight for modern single-engine propeller planes is usually between 1:2 and 2:3. Aircraft in the 1920s, especially biplanes, usually had a higher ratio (less loading capacity relative the weight), but given the anotar’s strong engine (which allows for more cargo in relation to overall weight) it can probably be assumed that it is closer to modern planes. The empty anotar’s weight therefore approximates (very roughly) some 2,000 lbs (907 kg).

Design

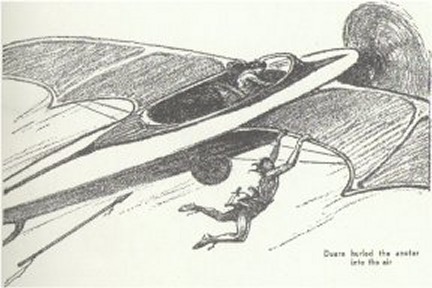

Here is an artist that had at least read the story. The bat wings are a nice touch, but the rear cockpit should be covered. St. John pulp magazine art (EV/39).

Carson describes the anotar as “such a ship as, I truly believe, might be built nowhere in the universe other than in Havatoo. Here I had at my disposal materials that only the chemists of Havatoo might produce, synthetic wood and steel and fabric that offered incalculable strength and durability combined with negligible weight.” (LV/16)In at least two ways Carson was ahead of his time. Firstly, he designed the plane “with retractable pontoons as well as ordinary landing gear.” (CV/1) The landing gear is also retractable (and probably independently from the pontoons), as becomes obvious when Carson mentions that “I hadn’t retracted my landing gear” (EV/19) outside Japal.

Secondly, he probably made the plane into a mid- or low-winged monoplane. This cannot be proved through the canon, but there are strong indications. For instance, when Duare climbed out of the plane the first time in Sanara “she stepped onto the wing” (CV/5). Note that it does not say “the lower wing,” so there is probably only one wing and it is definitely placed below the rim of the cockpit. This is all the more reasonable given that Burroughs’ Security Airster was a low-winged monoplane with the wing below the cockpit.

What little we see here is fairly well in line with Burroughs. The wings are low and there is a strut that suggests pontoons. Matania anotar art (LV/21).In 1931, neither low-winged monoplanes nor retractable landing gears had come into fashion. However, it is not strange that Burroughs should let his hero be thus advanced. By 1937, low-winged monoplanes and retractable landing gears were standard fare, especially on new military aircraft.

Nor do Carson’s advanced features need be very strange from an intratextual point of view. Remember that one of the aircraft he may have previously flown, the LW-2, was a low-winged monoplane. As for landing gear, the main reason why retractable gear was not popular earlier is that the retraction mechanisms available were too heavy and also made the gear too vulnerable when landing on the rough fields of the day. With the wonderful synthetic materials of Havatoo, neither would be a problem.

Practically nothing else is said about the shape or size of the wing. We can, however, draw some conclusions from the plane’s performance. Its good low-speed performance suggests a large wing area, which in turn could mean a rather wide span. But a wide span does not go well with the high maneuverability of the craft. Thus, in order to achieve both these characteristics, we must assume relatively short and broad wings. Broad wings does find some support in the text as Duare was “Climbing forward on the wing” (EV/37) in order to refit the propeller. The fact that she could seemingly stand on the wing to do this also indicates that the forward edge of the wing is close to the nose. Looking at the other planes that Carson has experience from, a wing span of about 40 ft (12 m) seems reasonable. The wings probably have no flaps. Flaps of all kinds were extremely uncommon before the 1930s, and the fowler flap, which expands the wing area, was not even invented until the mid 1930s.

Nothing is said specifically about the colour of the anotar. However, when talking about the shields of soldiers outside Sanara, Carson explains the following: “These shields are composed of metal more or less impervious to both r-rays and T-rays; [...] every portion of the ship [anotar], whether wood, metal, or fabric, had been sprayed with a solution of this ray-resisting substance” (CV/4). This probably means that every part of the anotar is “coloured” in some kind of metallic. The exception is the propeller (see below) during the second half of Escape on Venus, after its repair in Japal. (This does mean that the Falsans should have been unable to shoot off the craft’s nose, as they nevertheless did in EV/43.)

We know a few other things about the design of the craft. “It seated four, two abreast in an open front cockpit and two in a streamlined cabin aft” (CV/4). The open cockpit only has a windshield for protection (EV/37) and so must be extremely inconvenient at high speeds. Yet the pilot always seems to be seated there. The anotar must have position lights since Carson once flew “without lights” (CV/13). There is a fresh-water tank built into the craft (CV/4). It also has an anchor that can be dropped when landed on water (EV/40).

All the above design details refer to Mk I. The few things we know about Mk III correspond well with these. The Mk III also has (at least) two cockpits, each probably accommodating two (WV/2). Like its predecessor it also has a retractable landing gear (WV/3).

Engine and Instruments

Carson says that “the motor was a marvel of ingenuity, compactness, power and durability combined with lightness of weight” (CV/4). “Silent, vibrationless, and it required no warming up.” (LV/21)The engine, then, is powerful. But exactly how powerful? 480 mph is even today an impressive speed for a single-engine propeller plane, but far from impossible. The 1944 prototype aircraft Republic XP-72 had comparable performance. This was accomplished with a massive 3,000 horse-power engine. Calculating the power for the anotar engine is not possible with the available data, but given that the anotar weighs about 1/5 of the XP-72, we can approximate an engine that is weaker by the same degree. In other words, 600 hp would be a possibility.

The key to the engine’s secret is its fuel: “I had also the element, vik-ro, undiscovered on earth, and the substance, lor, to furnish fuel for my engine. The action of the element, vik-ro, upon the element, yor-san, which is contained in the substance, lor, results in absolute anihilation of the lor. [...] Fuel for the life of my ship could be held in the palm of my hand, and with the materials that entered into its construction the probable life of the ship was computed by the physicists working on it to be in the neighborhood of fifty years.” (LV/16)

We also know a few things about the propeller. We know that it is nose-mounted because when the anotar was shot down, “the nose of the anotar disappeared, together with the propeller.” (EV/43) The propeller is two-bladed, as is apparent from the remains of a broken propeller: “one blade and the stub of the other.” (EV/22) It is in fact the only individual part of the entire craft for which we know what material it is made of, since Carson talks about “the wood of which I had made this propeller” (Ibid.). The propeller is bolted with two bolts to a flange which in turn connects to the engine through the crankshaft (EV/37).

Little is known about the anotar’s instrumentation, except that it has “blind flying instruments on the instrument board” (CV/4) and that Carson “had built a compass in Havatoo” (EV/30). These blind flying instruments are probably none too complicated. For instance, there cannot be a ground radar of any kind (even though such would certainly be possible given the technology available in Havatoo) since that would have allowed safe flight through the clouds. The Tiger Moth with only seven instruments on its panel is probably a good point of reference here.

In flight, the craft is controlled with a normal control stick (WV/2). “[There] were controls in both cockpits, and the ship could be flown from any of the four seats” (CV/4).

Design Problems

For the ERB-APA publication of this article, I had an artist working on an original illustration. While sketching, the artist discovered several weaknesses in Burroughs’ design.Most weaknesses center around the use of retractable pontoons. Even if the anotar is very light in its construction, the pontoons nevertheless have to be rather large, since much air is needed to provide the necessary buoyancy. Pontoons that large would cause heavy drag whether retracted or not, even though my technical consultant says that the space inside the wings, not being needed for fuel storage, might offset that problem.

Another possible solution is that the anotar actually floats on its body, just like the Sikorsky S-38, and that smaller pontoons are lowered from the wings in order to provide stability. The problem here is that the wings and the engine are placed too low and would be in the way when landing and taking off.

In the end, we settled for pontoons that partly “merge” with the fuselage when retracted, though this would probably give some very funny take-off and landing performance, and be in the way of the retractable landing gear.

Another potential weakness is the propeller. A two-bladed propeller, able to pull 3,500 lb worth of loaded aircraft with a large wing area at 480 mph, would in all likelihood result in an extremely high-pitched whining engine noise, making any conversation in or around the craft impossible. The strain on the hand-crafted wooden propeller blades would be tremendous, so we must assume that Amtorian wood is astonishingly durable.

I strongly suspect that Burroughs did not have a very clear view of what the anotar looked like when he started writing about it. Later, he probably imagined something vaguely like his own Airster and, as the plot required, he added new features when needed. The result was a bird that does not quite fly.

But Burroughs was a writer, not a mechanical engineer. The anotar is a plot device, and very well-designed as such. Whether it would fly in real life is of little importance, as long as it continues to fly in our imaginations.

Click for full size

This anotar is certainly imaginative, which is perhaps the bottom line of any anotar design. The wings can seemingly be swept back for better high-speed performance, but the craft seems too narrow to seat two side by side. Carson of Venus cover art by Roy G. Krenkel.

Sources

Primary sources (by Edgar Rice Burroughs):

1. Pirates of Venus [PV]

2. Lost on Venus [LV] (paperback version)

3. Carson of Venus [CV]

4. Escape on Venus [EV]

5. The Wizard of Venus [WV]Secondary sources:

• Edgar Rice Burroughs: Bio Timeline; https://www.erbzine.com/bio/

• Fredrik Ekman; Chronology For E. R. Burroughs’ Venus Series; 2006; https://www.erbzine.com/mag16/1631.html

IMAGES OF AMTOR II (LV) by Matania; https://www.erbzine.com/mag2/0254.html

Many sources on aeronautics have been consulted. The following has been one of the most important:

• The Aero Files; http://www.aerofiles.com/

This article is featured in our

Fredrik Ekman Tribute Series

BILL HILLMAN

Visit our thousands of other sites at:

BILL and SUE-ON HILLMAN ECLECTIC STUDIO

ERB Text, ERB Images and Tarzan® are ©Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.- All Rights Reserved.

All Original Work ©1996-2024 by Bill Hillman and/or Contributing Authors/Owners

No part of this web site may be reproduced without permission from the respective owners