Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute and Weekly Webzine Site Since 1996 ~ Over 15,000 Web Pages in Archive Volume 7975a |

Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute and Weekly Webzine Site Since 1996 ~ Over 15,000 Web Pages in Archive Volume 7975a |

When I started writing my book Jetan: The Martian Chess of Edgar Rice Burroughs in 2018, I was certain that I was going to have to include every little fragment of information that I could find, in order to be able to fill an entire book with nothing but jetan. But in the end, it turned out that I needed to cut segments that I felt were unnecessary and superfluous to achieve the right balance of contents. The following text, which has been extended and edited to work as a stand-alone article, is a sample of what was cut from the final edition of the book. The text was originally published in ERB-APA #144. For what it is worth, enjoy!

“Jet-an” and the Movie that Never Was

By Fredrik Ekman

Originally published in ERB-APA #144

When A Princess of Mars finally made it to the big screen in 2012 with the bland title John Carter, it was far from the first attempt to adapt the book to moving pictures. Trying to find information about the various John Carter movie projects that never became reality, some are definitely better documented than others. It is easy to find something about, for example, Bob Clampett’s animation project from the 1930s, John McTiernan’s failed attempt in the 1980s, or the 1990s Paramount incomplete production with Robert Rodriguez signed as a director.

But for some reason, it is nearly imopssible to find anything about an attempt that was apparently made in the 1960s. I have found two remainders of this never-made movie.

My first lead that this film had been in the works was a screenplay by Anthony Wilson that I got hold of in the 1990s. It is 133 pages with a green Frazetta cover. There also appears to have been a limited edition (possibly a different version of the script) with a completely unrelated cover showing John Carter fighting morgors. The screenplay was undated, but through news items in old fanzines, I have come to the conclusion that it was written in 1965.

The second lead, which I found about the same time, although it took me a while to realize they were from the same source, are a set of numbered paintings by Bruce Grimes. Too detailed for storyboards and too sketchy for concept art, they illustrate the story in Wilson’s screenplay, although they do not agree with it in every detail. There seem to have been originally between 90 and 100; I have digital copies of 64, mostly downloaded from Grimes’ now defunct home page, and many in low resolution.

Wilson, for the most part, follows the original book fairly closely, at least in the outline, but he makes one major deviation: The climax of his story is not the war against Zodanga (the entire city is cleanly cut from this telling), but instead a game of living “jet-an” (sic), clearly inspired by The Chessmen of Mars.

Wilson changes many things in the game, as we shall see. Exactly why he had to muck about with the rules of jetan is a question which we shall never find an answer to. Perhaps he thought that the game in the book was too confusing to the eye with its multitude of pieces. Be that as it may, the screenplay is almost detailed enough that the rules of jet-an can be reconstructed. We only need to fill in a few piece movement patterns and the like.

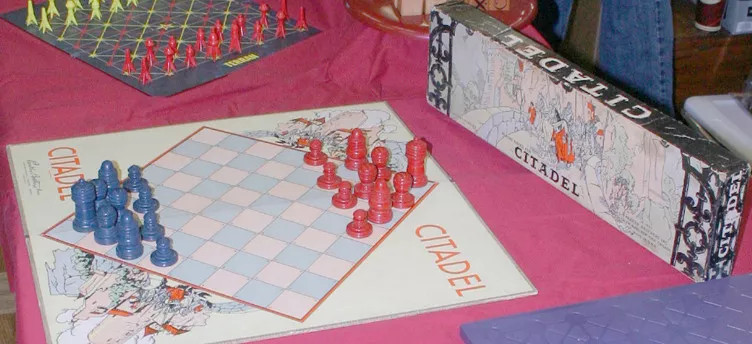

In constructing his game variant, Wilson was obviously inspired by a game titled Citadel, published by Hasbro in 1940. The setup is almost exactly the same, except the board is eight by eight, and the four types of pieces are set up slightly differently.

Image source: https://boardgamegeek.com/image/325031/citadelWilson first describes the game on page 83 and following pages. There, he gives a fairly detailed description of the board and the pieces:

“The gameboard is diamond-shaped and divided into ten rows of diamond-shaped squares. There are ten men on a side that are ranged in four rows from the apex of each side. The first row facing the opposite side is composed of four plain, pawn-like figures; the second row back has three somewhat larger pieces and the third row two still larger ones. The largest piece of all stands in the single space at the point of the apex. Somewhat in the manner of a goalie, it stands in front of a final piece that is actually one space off the board. This piece, on an unusual pedestal, cannot move its position and the conclusion of the game comes with the capture of this piece by the opposing team.”We later learn that these pieces, in order as they are described, are panthans, dwars, padwars, chief and princess. (Note that this is illogical, since in normal jetan dwars (captains) are more powerful than padwars (lieutenants), so the names of these two pieces should reasonably be reversed.)Jet-an is mentioned again on page 99. This time we do not gain much information, except that jet-an pieces appear to capture in the same way as chess and normal jetan pieces do. There is also a description of a jet-an piece, presumably a panthan: “It seems to be the figure of a man, unarmed and naked save for a loincloth.”

The living jet-an game is on pages 104 through 120 (the jet-an action starts on page 110). For the next few pages, the opening moves of the game are described. There are no details about how the pieces move, but we are given a few hints that allow us to reconstruct some possible movement rules: The first move in the game is an unspecified black panthan, who moves ahead three steps. Orange responds with a move that diametrally mirrors black’s. Black next moves a dwar to attack orange’s panthan, a move which is apparently legal, but unethical in the living version, where panthans are expected to meet panthans, etc, at least initially. The dwar, better armed, easily wins.

Orange’s second move is to move out with the panthan next to the first one. This is John Carter, who is forced to attack the victorious dwar. Carter, naturally, wins, but black counters with a padwar, in this game an even more formidable foe. Carter wins once again, but refuses to kill his opponent, and is ordered back to his starting square. That is the last move that is described in any kind of detail.

As can be seen from this description, the moves are vaguely defined, but it appears that all pieces have a lot of freedom of movement, and also that they can reach pretty far. The panthan can move at least three squares initially (to the middle of the board); the dwar standing behind at least one square more, and the padwar, even further back, at least two squares more than the panthan.

It seems pretty clear that Wilson never made the rules explicit, even to himself. His purpose was to make a dramatic segment for the screen, not to create a fun and playable game. Even so, we can easily create rules for movements that are consistent with the script and, though somewhat contrived, give us a playable game. The following is one possible interpretation that tries to retain some of the original ideas used in Burroughs’ jetan.

Note that since the board is aligned differently than a normal jetan board, the terms “diagonal” and “orthogonal” (straight) are not entirely transparent. I have chosen to let “orthogonal” refer to “northeast”, “southwest”, etc, i.e. along the lines of squares, whereas “diagonal” refers to “south”, “east”, etc, i.e. along the corners of the squares.

The panthan moves one, two or three steps diagonal forward or orthogonal forward. It can also move two plus two steps: first two diagonal forward, and then change its direction by 45° for two steps orthogonal. It can move a single step orthogonal backward. The panthan cannot move diagonal backward or sideways.

Jet-an panthan.The dwar moves seven orthogonal steps in any direction. It can either move straight in the same direction (like a chess rook), and then it can stop its move at any point (a movement pattern sometimes called “free” in jetan literature), or it can change direction 90° once during its move, but then it must move all of its seven steps (“chained”). If it changes direction and another piece stands in its way before it has moved all seven steps, that way is blocked and it has to make another move.

Jet-an dwar.The padwar moves five diagonal steps in any direction. It can either move straight in the same direction (like a chess bishop); and then it can stop its move at any point; or it can change direction 45° once during its move, but then it must move all five steps; those after the change of direction will be orthogonal. If it changes direction and another piece stands in its way before it has moved all five steps, that way is blocked and it has to make another move.

Jet-an padwar.The chief moves up to three steps, orthogonal or diagonal, in any direction or combination. This is equivalent to the standard jetan chief.

Jet-an chief.No jet-an piece can jump over other pieces.

In jet-an, the only winning condition is that the princess must be taken. This is probably done by placing any of your pieces on the apex square where your enemy’s chief was originally positioned, and then on the next turn move your attacking piece onto the princess’ position outside the board. No draw conditions are described, although it can be assumed that an endgame with only chiefs is impossible to win, so if only the chiefs are left and neither player has reached the opponent’s apex within two moves, the game is drawn.

Jet-an has never been tested in real play. Not by me, and certainly not by Wilson. With the rules described here, it should be possible to play, and potentially fast and furious in spite of the large board and few pieces. Whether it is also fun and interesting is left for someone else to find out.

Jet-an can be played by turning your normal jetan board 45° and using a subset of your normal pieces, plus you are going to need an extra dwar for each side.

The diagrams were produced with Zillions of Games and GIMP, using graphics created by Larry Lynn Smith. Used by permission.

ERBzine REFERENCES

Exploring Jetan By Fredrik Ekman

The Rules of Jetan, or Martian Chess By ERB, edited by Fredrik Ekman

John Carter - The 2012 Movie

The Chessmen of Mars (full coverage including e-text and Jetan rules)

Original John Carter 1936 Animated Film Project with JC Burroughs & Bob Clampett

All ERBapa Contents/Credits

A Princess of Mars

Players and Moves for Jetan-Sarang by James Killian Spratt

Unreleased Dell Chessmen of Mars Art by Russ Manning

The Field of Jetan at Manator

A Few Thoughts about ERB’s Jetan

This article is featured in our

Fredrik Ekman Tribute Series

BILL HILLMAN

Visit our thousands of other sites at:

BILL and SUE-ON HILLMAN ECLECTIC STUDIO

ERB Text, ERB Images and Tarzan® are ©Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.- All Rights Reserved.

All Original Work ©1996-2024 by Bill Hillman and/or Contributing Authors/Owners

No part of this web site may be reproduced without permission from the respective owners