Official Edgar Rice Burroughs Tribute and Weekly Webzine Site

Since 1996 ~ Over 15,000 Web Pages in Archive

Volume 7985Did Ivor Thord - Gray Find Tarzan?

By Fredrik Ekman

Originally published in ERB-APA #155.

The Man Who Found Tarzan

The adventurer, soldier and businessman Ivor Thord-Gray was a fascinating man. Born as Thord Ivar Hallström in 1878 (three years after Edgar Rice Burroughs), he was dissatisfied with the quiet and peaceful life cut out for him in his native Sweden. So, 17 years old he decided to see the world. He enlisted on a merchant ship and signed off in South Africa.

His many adventures in all corners of the world are too numerous to tell here, but in South Africa he joined the British army to fight in several conflicts, including the Second Boer War. During his lifetime, he was a soldier and an officer under 13 different flags and banners, including the revolutionaries in the Xinhai Revolution in China, Pancho Villa in the Mexican Revolution, England in World War I, the White Army in the Russian Civil War, and the United States in World War II (although he never went overseas in that conflict).

He also set an archery world record in 1927 (48 years of age!), he was an acknowledged ethnologist and linguist (Ph. D.) studying Native Americans in Mexico, he became a banker in New York, and many other things.

Ivor Thord-Gray, who had become a U.S. citizen in 1934, died in his home in Florida in 1964.

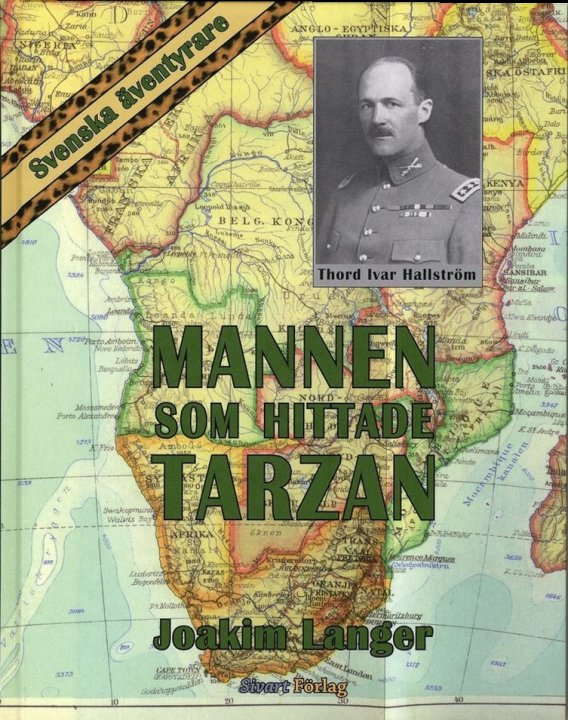

In 2008, two very different books about Thord-Gray were published in Sweden. The first, Ivor Thord Gray: soldat under 13 fanor by Stellan Bojerud, focused on his military career and will not be further discussed here. The second focused on Ivor Thord-Gray as the man who “found Tarzan” and inspired Edgar Rice Burroughs to create his literary character. The book, by Joakim Langer, is titled Mannen som hittade Tarzan – ‘The Man Who Found Tarzan’.

The focal event of the book is a meeting that took place in a Cape Town hotel in 1906. A journalist conducted an interview with Thord-Gray about his recent involvement in the Zulu War. As a curiosity, Thord-Gray told the story of how he, back in 1898, had seen a troop of baboons running up an escarpment. One of the baboons had fallen down and died, and upon inspection, it turned out that it was a human child. In the nearest village, Thord-Gray found out that the child had been stolen by the baboons a couple of years earlier. The baboons had left a dead baby baboon behind them by the empty baby stroller (uncannily similar to the Tarzan origin story). The journalist printed the story in his newspaper; it later spread to newspapers in England and the United States, and thereby came to inspire Edgar Rice Burroughs to write Tarzan of the Apes.

Many sources (not including Langer, it should be pointed out) even claim that the journalist in Cape Town was Edgar Rice Burroughs, which is obviously ludicrous, since it is well documented that Burroughs never visited Africa. It has also been suggested (again, not by Langer) that Burroughs and Thord-Gray may have met when the latter was on his way to join the Mexican Revolution. Both men were in California in late 1913, so such a meeting is possible. But the timing is off – Tarzan of the Apes had already been published in the pulps in 1912.

Langer’s book is a fun read and very interesting, but it suffers from one major problem: it lacks balance. Langer has done a very thorough job researching the life of Thord-Gray, even down to travelling around the world to visit places that were important in Thord-Gray’s life, and to talk to his descendants and others who came in contact with him. But he did almost no research at all on Burroughs and Tarzan. The book includes three brief sidebars with facts about ERB and Tarzan, but they are superficial and sometimes incorrect. Interestingly, the otherwise profusely illustrated book contains only a single image of Tarzan (a photo of Johnny Weissmuller) and none of Edgar Rice Burroughs.

If Langer had only bothered to read one book about ERB, Edgar Rice Burroughs: Master of Adventure by Richard Lupoff, he would perhaps not have been so certain in his conclusions. Chapter 15 in that book contains a very interesting theory regarding what sources inspired Burroughs to write Tarzan. It tells the story of Professor Altrocchi and his search for Tarzan’s literary ancestors. Following in the steps of Altrocchi (who corresponded extensively with Burroughs himself), Lupoff concludes that Burroughs mainly had three sources of inspiration: Kipling’s The Jungle Book, ancient legends such as Romulus and Remus, and an unidentified story about a sailor who was shipwrecked among apes on a desert island. Thord-Gray, with his South African escapade, is not mentioned at all. Burroughs partly confirms this in a 1938 interview:

“As a boy I loved the story of Romulus and Remus, who founded Rome, and I loved too, the boy Mowgli in Kipling’s ‘Jungle Books.’ I suppose Tarzan was the result of those early loves. Perhaps the fact that I lived in Chicago and yet hated cities and crowds of people made me write my first Tarzan story . . .” (Edgar Rice Burroughs Tells All, p. 361)

Lupoff’s account and Burroughs’ quote clearly contradict Langer’s hypothesis, that Burroughs’ main inspiration comes from Thord-Gray. Does that mean that Langer is entirely wrong? Not necessarily. In a 1937 letter, quoted by Lupoff, Burroughs says: “I imagine that in the past twenty years several thousand people have asked me the same question [how I got the idea for Tarzan] which I wish I could answer definitely.” (Master of Adventure, 1968 paperback edition, p. 223)

In other words, it is very possible that, in addition to the sources mentioned, Burroughs may have read about, taken inspiration from, and subsequently forgotten about Thord-Gray’s adventures. But Langer’s claim that it was the main, let alone only, source of inspiration must unfortunately be dismissed.

An aggravating circumstance for Langer is that he was unable to find the actual newspaper clipping that purportedly inspired Burroughs. In the years that have passed since Langer’s book was published, the possibilities to search old newspapers in online archives have increased enormously, and I have made my own attempts to find such a clipping. But to no avail. I searched practically every English-language newspaper archive that I could find, including newspapers.com, the world’s largest online newspaper repository, but my efforts came up blank. There is not a single hit on any relevant article about Ivor Thord-Gray, neither when I search his name (with various spellings), nor when I try other combinations that might be relevant, e.g. “South Africa boy dead raised baboons”.

Even this is not proof against Langer’s ideas, since there must be thousands upon thousands of newspapers out there, waiting to be scanned and digitally archived. Still, until such a clipping can be found in a newspaper that Burroughs may have reasonably read, Langer’s theory is little more than an interesting curiosity.

In the book’s final paragraphs, Langer puts forth his final “evidence” that Thord-Gray inspired Tarzan, namely the auditory similarity between the name Thord-Gray (originally spelled “Thord-Grey”) and Tarzan’s “civilian” name Lord Grey(stoke). Personally, I do not see this as evidence of any sort or description. Burroughs originally considered the name “Lord Bloomstoke”, and he had already used the name Greystoke in an unrelated novel. There is no reason to assume that he consciously constructed the name to be similar to Thord-Gray’s, even if he had been inspired by the latter’s story.

It is unfortunate that Langer puts such great emphasis on this one small detail in Thord-Gray’s life, for his book is otherwise a fascinating account of a man whose life reads like something that could have been invented by the Master of Adventure himself. For anyone who can read Swedish, I must highly recommend it, but take the Tarzan connection with a large grain of salt.